How ‘Citizen Science’ is Helping Save China’s Environment

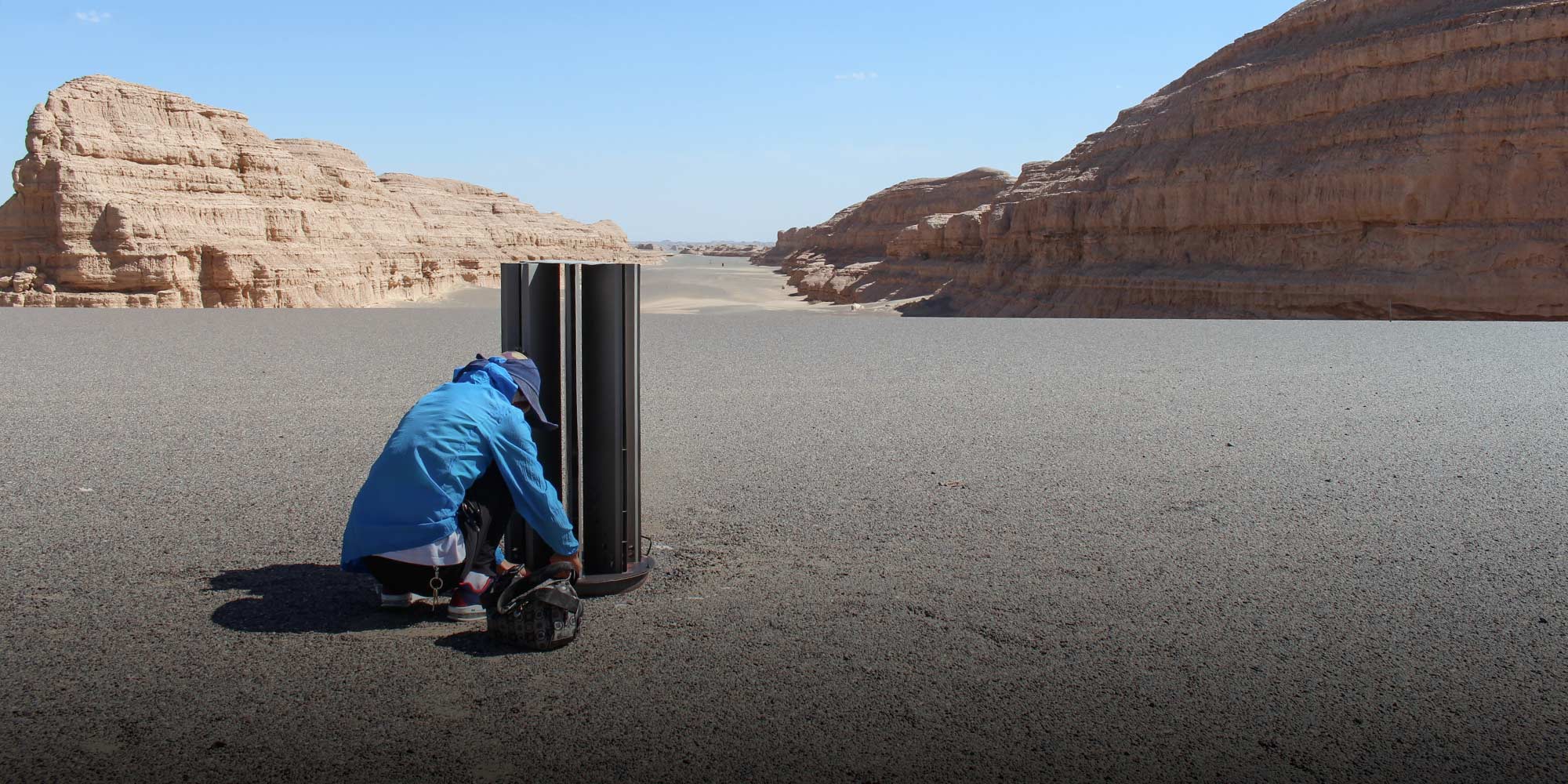

The desert winds rolled in like waves off of Yadan National Geological Park in northwest China’s Gansu province as I watched my companion take readings from a sand monitoring station sunk into the soil a few meters away. I’ve spent the better part of the past two years working with environmental NGOs across China, and I took the moment to reflect on the environmental, cultural, and economic diversity I had witnessed during that time.

The litany of environmental problems facing China is well-known. Factory waste is polluting the country’s waters, while coal and exhaust from cars has smothered its cities in smog. Rapid urbanization has caused flooding in some parts of the country, while overuse of the land is driving desertification and grassland degradation in other areas. Diverse challenges require diverse solutions, and over the past two years, I’ve learned much about how Chinese conservationists are working to protect China’s vast, varied, and fragile ecosystems.

Solving China's environmental problems will require huge investments not just of capital, but also time, personnel, and technology. Local capacity must be built up. It would be easy for environmental groups to fall into the same trap that has plagued development organizations for decades — outsiders with money and technical expertise offering a one-size-fits-all approach to aid that is not necessarily suited to the region in which they are working. If China wants to avoid such pitfalls, it is important to take local views and traditional practices into account when planning future environmental protection and monitoring efforts.

According to Zhao Zhong, founder and director of the environmental NGO Green Camel Bell, this is where NGOs can help — by functioning as a bridge between local residents and outside scientists. “This type of work might happen without NGOs, but it is highly unlikely,” says Peng Kui, program manager of the Global Environmental Institute (GEI), who also believes in the importance of NGOs as intermediaries between local experience and high-level scientific knowledge.

According to Peng, most environmental work is done one of two ways. “Scientists either go somewhere and tell the people there what to do, in the belief that modern science has found the best way to address the issue — though local people often don’t want to adopt their suggestions, because they seem inaccessible and far removed from traditional methods,” he says. “Or local people just do as they see fit. But when they explain their reasoning, outside scientists may not necessarily believe them in the absence of full accounts of data and proof — they feel opinions aren’t quite scientific without them.”

This is where NGOs come in, by helping close the gap between local residents and scientists. One side comes equipped with traditional methods and an understanding of the area; the other has access to needed funding, equipment, and scientific knowledge. The two function best when combined. Afforestation efforts in Gansu offer an example of how local knowledge of plant life can be joined with a scientific approach toward planting to help achieve environmental goals.

One increasingly popular method by which NGOs are helping to facilitate cooperation between locals and outside scientists is known as “citizen science” — a means of environmental monitoring and protection that works to involve local residents in scientific work, such as data collection efforts.

With the popularization of big data and social media, citizen science — which can involve anything from locals monitoring and reporting wildlife sightings on smartphone apps and residents taking photos of water pollution, to herdsmen keeping an eye on grasslands and tracking desertification — has become increasingly common around the world. In China — where traditional knowledge and practices still carry significant weight — it is proving to be an indispensable tool. As Peng explains, traditional and more scientific practices “are both useful, but there is a gap between them, and we began to realize that citizen science could help fill that gap. This way, scientists can conduct their studies, and local residents can still make use of their traditional expertise.”

This respect for traditional and local expertise is being emphasized by NGOs throughout China. The Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs(IPE) runs the “black and smelly river” program, partnering with small, locally-based NGOs around the country to get detailed, on-the-ground contributions from those most familiar with the situation. Other NGOs, such as GEI and Green Camel Bell, have worked with herders on grassland conservation and anti-desertification efforts in Gansu and Inner Mongolia. As Shen Sunan, a senior researcher at IPE, explains, “we have to rely on local people to solve local problems.”

In addition to their work with local groups, Chinese environmental NGOs are also partnering with scientists to ensure that the data being collected is useful. Scientists provide much-needed know-how by creating data collection forms and apps, providing equipment, and assisting in data analysis and verification. Feng Chen, project coordinator at Shanshui's China Nature Watch, says organizations like Shanshui have partnered with Peking University doctoral students at the Center for Nature and Society to go through and check the data to make sure that it is up to scientific standards. The Rock Environment and Energy Institute (REEI) and IPE both use similar procedures with their data. Meanwhile, public data collection has also led to increased transparency for “data that often had gaps or was unavailable to the public,” according to Feng.

Citizen science does more than just allow locals to participate in the data collection process: It gives urban and rural residents alike a chance to learn more about their environment and take an active role in its conservation. Given the vast array of environmental challenges China is facing, there can be no one-size-fits all solution. Instead, we must include members of the public in the scientific process and respect the traditional and local knowledge they can offer. Only then can we forge the environmental awareness and individualized solutions the country needs.

Editors: Zhang Bo and Kilian O’Donnell.

This article was funded by the Sixth Tone Fellowship. In 2018, Sixth Tone sponsored eight young scholars to come to China for a six-week research trip to conduct fieldwork in eight provinces all over the country.

(Header image: A local assistant takes readings from a sand monitoring station in Dunhuang, Gansu province, June 12, 2018. Lyssa Freese for Sixth Tone)