‘The Rap of China’ Returns After Off-Beat Year

Last summer, frizzy-haired Wang Shuyi was rapping in front of millions. Now, she splits her time between work and the gym, and occasionally busks for passersby.

Wang — who wears large wire-rimmed glasses and sports tattoos over her arms and neck — was one of dozens of contestants battling it out during last year’s “The Rap of China.” The show put contestants’ skills to the test in various rounds, from 60-second freestyles, to one-on-one rap battles.

On Saturday, the hit show will return for a second season on iQiyi, the online video platform dubbed “China’s Netflix.” The show will see 68 contestants rap and rhyme their ways through the elimination stages until one — or two, should they repeat last year’s controversial result — is declared champion.

But it’s a different world this time around. While last year’s show was praised for bringing hip-hop, including rap in different dialects, to the mainstream, the hype it brought about has also led to lows for the genre — and performers like Wang.

“Of the many variety shows I’ve seen in recent years, very few have been as influential as ‘The Rap of China,’” 28-year-old Wang, who hails from Guangzhou in southern Guangdong province, tells Sixth Tone. “Before this show, those of us that did [hip-hop] were seen as quite controversial; a lot of people … looked down on us and didn’t understand.”

Known as “An Dahun” on stage — a play on the Chinese word for “requiem,” chosen as a tribute to Mozart — Wang was initially nervous about how the commercialized show might affect China’s burgeoning hip-hop scene. The show seemed to run counter to the hip-hop philosophy of “keeping it real,” she says, slipping into English.

Wang gave it a go anyway. She found the myriad rules and truth-distorting editing frustrating, and was knocked back without explanation by the judges in the early stages. But the series — which attracted 2.7 billion views across the season — changed things for the young rapper. It boosted performance opportunities for her previously financially stretched hip-hop circle and saw her own fees soar from around 200 yuan per show to over 10,000 yuan ($30 to $1,500).

But the hip-hop hype didn’t last. In December, only three months after PG One and GAI were crowned the winners of “The Rap of China,” crisis struck. PG One found himself embroiled in one controversy after another: First, there were rumors of an affair with a married actress, then state media slammed his lyrics for glorifying drug use and objectifying women. His young army of fans fought back fiercely, with some even threatening to immolate themselves in protest.

The government’s response was swift: In January, authorities banned tattoos and all representations of hip-hop culture, such as flashy jewellery, from being shown on television — although the directive was vague about what was included in the ban. Artists with an association to hip-hop were suddenly dropped or cut from television programs. For rappers like former contestant Wang, the clampdown meant a marked reduction in gigs, and therefore income, as brands and events were afraid to associate with the blighted art form. She now wonders if she should reconsider her career.

Careful to avoid the now-sensitive word, the new Chinese name for the second season has changed from “China Has Hip-hop” to “China New Rap.” The show now promises a new look, more Chinese elements, a more diverse cast of contestants, and an emphasis on quality music over reality TV-style drama. The show is also bringing in extra judges, including the show’s first female judge — Hong Kong pop singer G.E.M. — and U.S. hip-hop trio Migos, who were invited to judge the show’s overseas selection round in Los Angeles.

Even without the added official pressure, the show would still have had a lot to live up to. After only the first episode of last year’s series, competition judge and singer Kris Wu’s catchphrase “Do you have freestyle?” became a viral joke, and before long, major brands such as e-payment platform Alipay were getting in on the trend with their rap-filled advertisements.

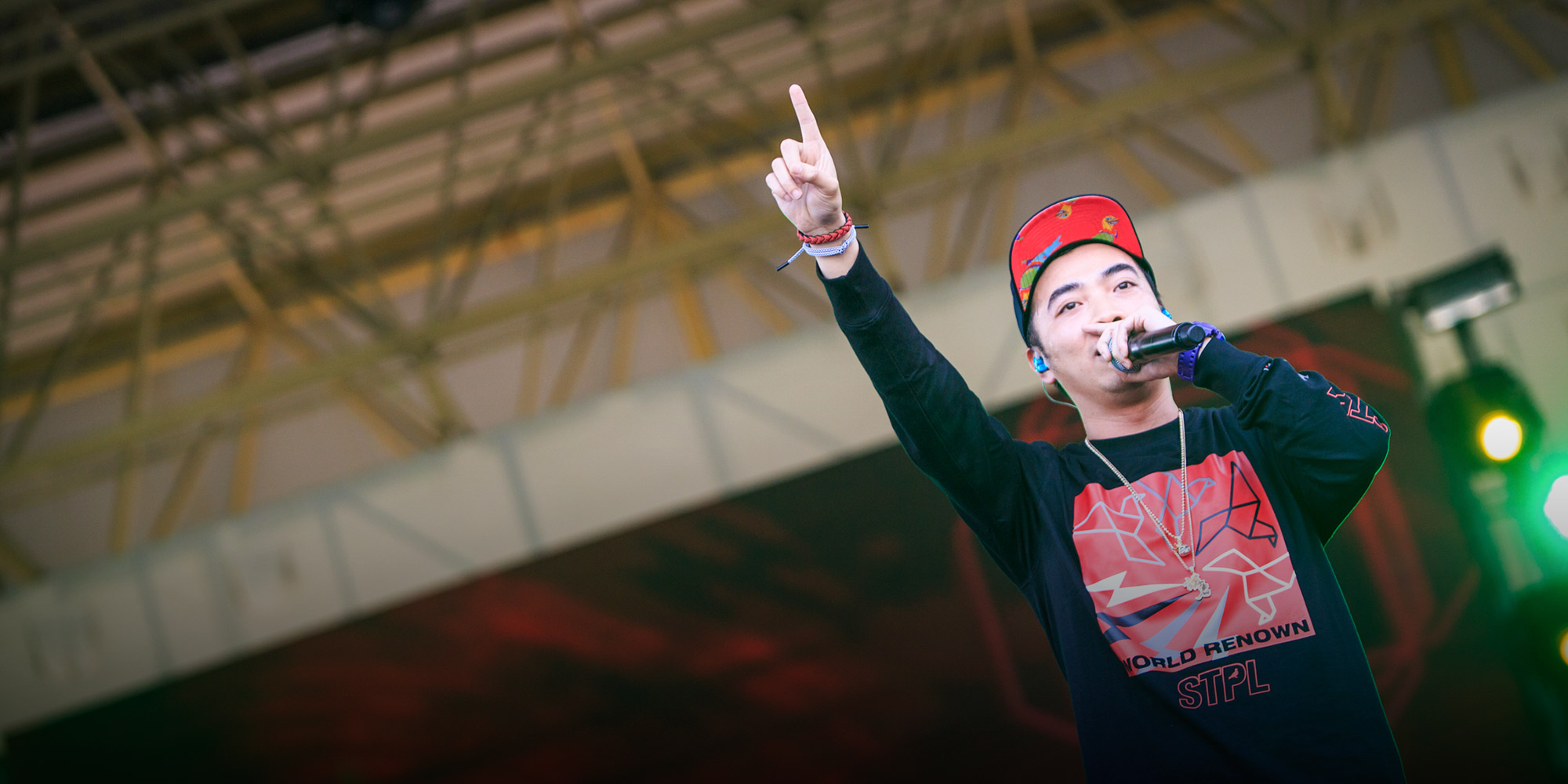

Guangzhou-based hip-hop artist Hu Ziwen — who has over a decade of rapping experience — was surprised when his once-niche genre was suddenly everywhere last year. After only two episodes had aired, the 33-year-old's group Prosa was asked to write and perform rap adverts for a car sales company.

“Hip-hop was absolutely everywhere: When you ate there was hip-hop, when you went swimming there was hip-hop. Wherever there was an event, there’d be hip-hop. It was so different from before,” Hu tells Sixth Tone. “A whole bunch of people who’d never heard hip-hop suddenly saw that it was popular and started listening to it and watching this show. But they didn’t understand hip-hop at all.”

After the backlash, being a hip-hop artist became a black mark, says Hu — who goes by “Fat B” due to his former large size and as a reference to “phat beats.” Music festivals have been either unable or unwilling to add rappers to their lineups for fear of potential repercussions such as last-minute cancellations. Hu still gets the odd small gig, but he feels he now gets fewer shows than he did before “The Rap of China” aired.

“After the PG One incident [with the lyrics], they don’t dare have hip-hop out in the open,” Hu tells Sixth Tone. “For any performance, when they hear you’re a hip-hop artist, they either can’t get you approved by the government, or they just say they don’t allow hip-hop artists to perform.”

Despite the crackdown, Hu decided to apply for this year’s show, but wasn’t accepted. He thinks his age and the fact that he mainly raps in Cantonese is to blame — although rappers who used different dialects were on the show last year, there was still a preference for Mandarin rap.

Hu’s not afraid of rap being suppressed entirely; instead, he’s worried that the entertainment industry will continue churning out rap shows until all of the commercial value has been squeezed out of it and people lose interest in the art form. It’s the ravenous “fast food culture” of superficial consumption without thinking that’s to blame for the crackdown, he says. “The Rap of China” made hip-hop too popular, too fast, causing both the good and the bad elements of the culture to be rushed in without a slow and healthy process of filtration and consolidation, according to Hu. When the movement seemed as if it was losing control, authorities became concerned about its influence on idol-worshipping youngsters.

But Hu’s very confident about the future of hip-hop in China — if anything, the strong social reaction to last year’s show proved that it’s what young people like. “People shouldn’t take this show too seriously,” he says. “If this culture can be allowed to develop slowly, hip-hop in China could become really awesome.”

Fellow artist Wang agrees that things moved too fast after “The Rap of China.” She’s particularly exasperated by how few people understand the art form’s roots and history, and how some think they can label themselves rappers after writing a few rhymes and putting them to a backing track. “I think that the development of any culture in our nation — be it hip-hop or any other — is a slow process. Right now, a lot of people have heard of hip-hop, but they still haven’t truly understood it,” she says.

As for the controversy that rap has attracted, Wang says that her fellow artists should just focus on improving their own music, rather than fighting with their critics. “Let nature take its course: It’s not like we can dictate the outcomes,” she says.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: Hu Ziwen performs in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, March 25, 2018. Courtesy of Hu Ziwen)