A Porous Border: China’s Berlin Wall

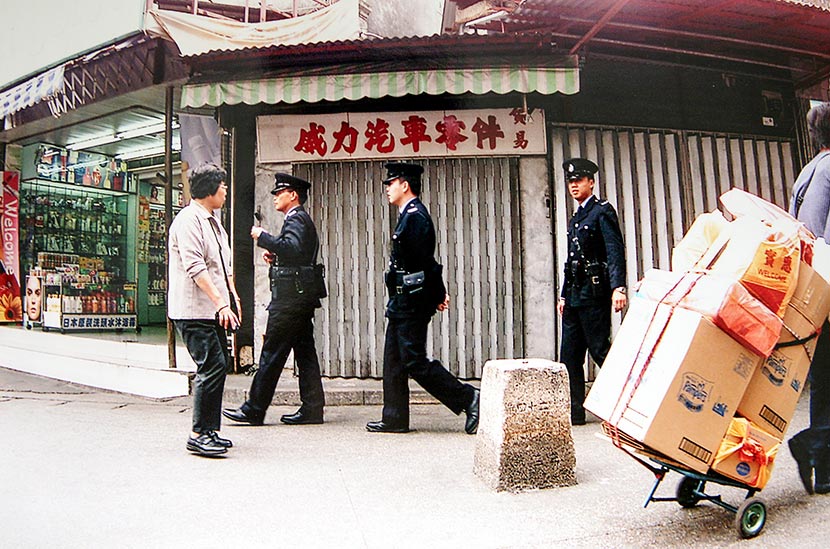

GUANGDONG, South China — People start lining up to enter Chung Ying Street while the morning sun is still drowsy, lolling low on the horizon. First-time visitors stop for photos before stepping toward the checkpoint with their entry permits in hand; regulars briskly stroll through with carts in tow, ready for duty-free shopping across the border, on the easternmost part of the boundary between Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

These days, the offerings on the 250-meter stretch pale in comparison to the dazzling displays available in megamalls or the convenience of online cross-border commerce. The draw of Chung Ying Street — which means “China Britain Street” — lies in its past, when it divided the British territory of Hong Kong from the rest of China, and later, when it marked the frontier between capitalism and communism. The lives of locals along the border embody each stage of China’s transformation.

The town surrounding the street is Sha Tau Kok, which is named after a dried-up mudflat on the estuary of Shenzhen River. In 1898, a convention between the British and the Qing Empire that then ruled China split the town, awarding the western side to the British as part of their 99-year rent-free lease on Hong Kong’s New Territories. The eastern side remained part of China’s Guangdong province. From 1899, Shenzhen River and Chung Ying Street formed the boundary.

Sixty-year-old Ng Tin Ki — or Wu Tianqi in Mandarin — lives just north of the river and says that his family have been farmers and fishers in the area for more than 300 years. Despite the division, he says that the interactions within Sha Tau Kok were largely unaffected after 1898. People from the mainland side still farmed their fields over the border, and relatives living on different sides continued to visit each other.

That changed after 1949 when the Communist Party took control of China. Barbed wire fences were installed as Shenzhen River and Chung Ying Street became part of the boundary between socialism and capitalism.

“People on the Hong Kong side thought socialism was new and unfamiliar. Women there felt afraid, and fewer were willing to marry those from the mainland side,” says Ng. In 1951, the Hong Kong part of Sha Tau Kok was declared part of the Frontier Closed Area, and even to this day, entry to the area requires a special permit for residents of both Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland.

During Ng’s childhood in the 1950s and 1960s, people in China’s planned economy could only obtain goods using coupons allocated by the central government. Ng remembers that residents of Sha Tau Kok received more coupons for cloth and rice than those in other areas because they lived in the “frontier of the frontier,” and the Chinese government feared that the town’s residents would abscond. In the early ’60s, when thousands of people from the mainland risked their lives to flee to Hong Kong following the Great Famine, Ng says he was unaware of the disaster inland, though his village was on one of the major routes for escapees.

Zheng Shaohui, now 62, had to go through strict security checks to get his job at a state-owned department store on the mainland side of Chung Ying Street. “In the shops here, we had products that were scarce inland, such as bicycles and electric fans,” he says. However, mainland residents could not enter the store, though it was operated by the mainland government — such treasures were only available to customers from Hong Kong as part of border defense strategies aiming to show the advantages of socialism.

A store employee by day, Zheng and his colleagues were armed with guns to patrol the border by night. “The atmosphere would grow tenser during festivals,” he recalls, adding that Kuomintang secret agents had in the past chosen festival days for operations targeting mainland facilities. “There were radio alerts of enemies [approaching], but I never knew whether the alerts were real,” he says.

The economic gap between the two sides of Chung Ying Street grew more and more palpable, Ng says. As part of the village fishery brigade under the people’s commune system, his annual salary in the early 1970s was as much as a worker would make in just a month in Hong Kong. As a result, some villagers slipped over the border to work in Hong Kong, where there was a larger demand for labor to sustain its rapid growth.

In the eyes of some economists, Hong Kong’s growth helped expedite economic reforms on the mainland. In 1978, China’s central government decided to introduce market principles to the economy and invite foreign investment — a policy known as “reform and opening-up.”

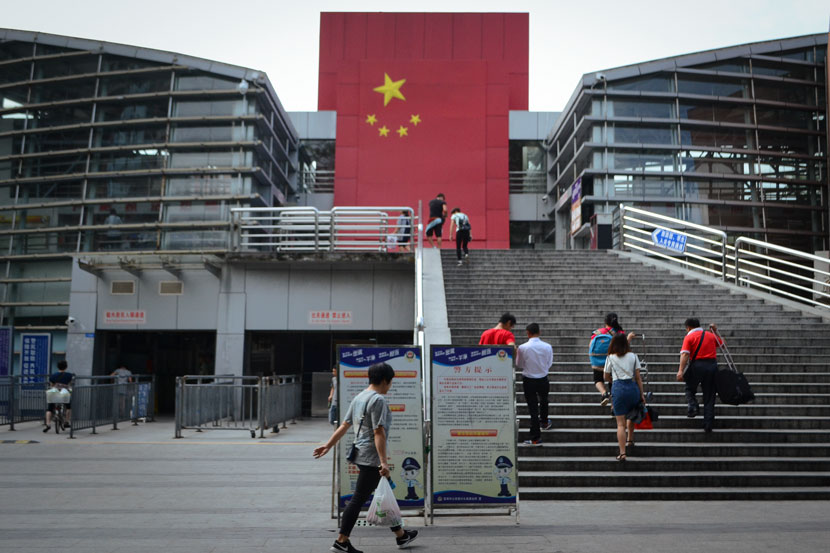

The area around Sha Tau Kok — formerly known as Bao’an County — was renamed Shenzhen and designated as the country’s first Special Economic Zone in 1980. “In the 1980s, industries in Hong Kong developed to such a degree that manufacturing industries could be expanded to the north,” says Zhang Yuge, a director at China Development Institute — a Shenzhen-based think tank focusing on China’s reform and opening-up.

Chung Ying Street’s location put it at the forefront of the opening-up policy. Hong Kong companies established leather processing factories in Ng’s village. When the fishery brigade folded, Ng started his own transport business using a minibus he bought in Hong Kong — an endeavor that would previously have been forbidden, because all private enterprise was seen as ideologically misguided. The GDP per capita in Shenzhen rose from 606 yuan in 1979 (then $75) to 11,997 yuan ($1,400) in 1991.

Where previously only Sha Tau Kok locals could enter the street from the mainland side, after reform and opening-up, any resident of the Chinese mainland could apply for a visitor permit to Chung Ying Street. With duty-free goods on both sides, the street saw its prime in the 1980s and 1990s as people from all over the country flooded into the street to get a glimpse of Hong Kong. At its peak, annual visitors reached 15 million.

“Many people would buy Yakult, a kind of fermented milk drink,” poet Wang Xiaoni writes in a recent article recounting the items people bought on the street. “It wasn’t until later that I discovered it was invented in Japan in the 1930s. All through the 1980s and 1990s, Yakult was synonymous with Hong Kong food.”

Gold topped the list of best-selling products, since it was much cheaper in Hong Kong. At least a third of the shops on the Hong Kong side of the street were gold dealers. People still share tall tales about how, at the peak of the roaring gold trade, dealers stuffed burlap sacks with cash they’d earned.

Aviator sunglasses, bell-bottoms, and Cantonese pop songs were other imports that changed mainland culture and popular thought, researcher Zhang says. He cites another example: the slogan “Time is money,” which was promoted by the Shekou Industrial Zone in Shenzhen.

“People suddenly realized that time could be related to money. Back then, who dared to talk about money? All people talked about were revolutionary ideals,” Zhang recalls.

The din of Chung Ying Street fades away in the long, narrow shop of 82-year-old gold dealer Wan Yam, who quietly watches the flow of visitors from his corner. Back in the street’s heyday, Wan could earn over 100,000 yuan a day despite fierce competition. But now, though his store is one of a few gold dealers still operating on the Hong Kong side, he only keeps one display of gold jewelry and says that he has fewer than half as many customers as before.

As people on the Chinese mainland gain more convenient access to international markets and consumer tastes change, the frenzied commerce that once typified Chung Ying Street has cooled down. To make matters worse, the street is plagued with fake products and gray market traders who buy products from the street and then sell them elsewhere at a markup. Because customs limits each shopper to 5,000 yuan of duty-free purchases, such traders carry goods out of the street in small lots, “like ants moving houses,” as Ng describes it. Some even approach individual tourists and pay them to take their goods over the border.

“Honestly speaking, if not for the shopping, there is not much to see because the street is so short,” says a tourist from Shanghai surnamed Feng. She says that she heard about the street from her high school history teacher.

It has been a challenge for the government to rejuvenate Chung Ying Street in the face of China’s economic boom. Near one end of the street, construction workers are renovating the Chung Ying Street History Museum, next to which sits a huge bronze bell. Every year on March 18 — the anniversary of the day that the Qing and British governments agreed on the boundary in 1899 — the bell tolls to remind people on both sides of the “humiliating” moment of partition as part of the museum’s patriotic education program.

But Lau Chi-pang, a professor at Lingnan University in Hong Kong who studies the history of Chung Ying Street, questions whether such activities actually advance patriotism. “Chung Ying Street is located in a remote, closed area, so this patriotic education won’t impact many young [Hong Kong] residents,” Lau says. “The biggest value of the street lies in its many historic relics, which show one of the borders between the Eastern Bloc and Western Bloc during the Cold War.”

Zhang agrees that the street is a testament to history. “If the economic reform had failed and we stagnated in the 1980s, Chung Ying Street would still be having as good a time as then,” he says. “It’s normal that it [now] attracts less notice. It is a witness, or a mirror.”

Tired shoppers stop to rest under an old banyan tree whose canopy leans toward the Hong Kong side of the street. “People here call this ‘the tree that betrays its parentage,’ because its roots are in the mainland, but its shadow covers the Hong Kong side,” a tour guide explains.

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: People stroll along Chung Ying Street, June 30, 2017. Liu Yi/IC)