What Chinese Opera Can Teach Us About Gender

In traditional Chinese opera, cross-dressing is common practice, with male actors performing female roles and vice versa. Dressing up as the opposite sex often serves as a metaphor for the loss of one’s identity or for gender dysphoria. Frequently, it also carries implications of same-sex romance.

Theatrical cross-dressing has roots in the restrictive gender norms of imperial Chinese society. During the Ming and Qing dynasties — two periods in which Chinese opera flourished — society controlled interactions between men and women much more strictly than today. Because it was considered improper for a man to appear onstage with a woman, opera troupes commonly employed either all-male or all-female casts.

The Qing Dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1911, witnessed the rise of Peking opera, now considered a high watermark of Chinese culture. At the time, imperial government decrees prohibited women from participating in, and even watching, operatic productions. But even in plays with mostly male protagonists, for example, there were usually a handful of female roles, too. Consequently, all-male troupes needed to cast certain men as women. Such actors became known as nandan, where nan means “male” and dan refers to traditionally female theatrical roles.

Although much Ming- and Qing-era art centered around the female ideal, in drama circles nandan culture came to be seen as the truest test of a male actor’s prowess. With the decline and fall of the Qing Dynasty, strict gender segregation came to an end, and mixed casts once again took to stages across the country. But the nandan tradition had sunk deep roots into Chinese theater by then, and cross-dressing culture continued to be tolerated across the country. Indeed, a 1927 review by the Beijing-based newspaper Shuntian Times, gave male actors the top four rankings in a list of the country’s best performances of female roles.

Nandan remain the most valorized roles in Peking opera. Similarly, nüxiaosheng — young male roles performed by women — are a product of Shaoxing opera, an eastern Chinese variant of the style. Shaoxing opera started out with entirely male troupes, but by the time it reached its heyday in the mid-20th century, all-male and indeed mixed casts were disappearing. In 1939, Shanghai boasted more than 20 Shaoxing opera troupes, all of which were entirely female. It is likely that the emergence of all-female casts was connected to an influx of women into theaters.

Audiences’ love of performative cross-dressing comes firstly from an appreciation for the high caliber of acting required to pull off the part. Roles like the nandan and the nüxiaosheng are complex and challenging because they demand that the actor break through the barriers of biology and gender, and reach toward an unattainable masculine or feminine ideal.

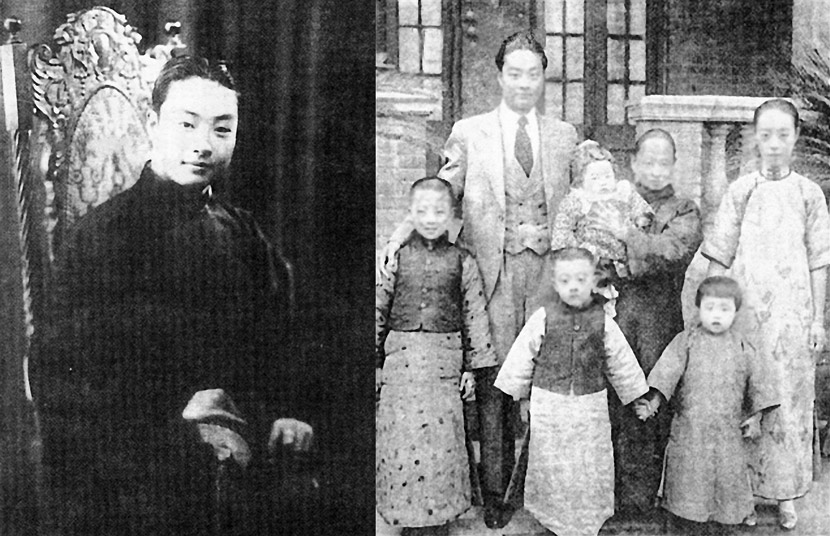

Performative cross-dressing is so enthralling because audiences are never allowed to forget the gender of the actors themselves. The greater the contrast between the actor’s onstage presence and their perceived “true” self, the more accomplished they are as an actor. Cheng Yanqiu, a much-loved nandan who lived in the first half of the 20th century, was a powerfully built man known for his forthright, direct personality. But on stage, twirling in circles and flourishing his silken sleeves, Cheng became an elegant, beautiful woman capable of striking myriad postures that tugged at the heartstrings. Cheng’s supreme technique came closer than almost anyone else to the nandan’s feminine ideal.

Many people misconstrue the nature of cross-dressing in Chinese theater, believing that only “effeminate” men can possibly play female roles and only “masculine” women can do the reverse. But performative cross-dressing does not necessarily favor an actor’s gender identity or personality type. Each of the five traditional opera roles, or jiaose, carries corresponding traits, including gender, identity, and temperament. After one or two years of training at an opera school, an actor will be assigned a jiaose according to their physical attributes, such as their build and voice — but, crucially, not their actual gender or personality. From there, they go on to study the entire package of skills that their jiaose requires.

When today’s audiences watch cross-dressing actors, they are perhaps moved on a psychological level that goes deeper than artistic appreciation. We might assume that male audience members favor female actors and vice versa, but Peking opera’s predominantly male clientele remain particularly partial to nandan, and Shaoxing opera’s largely female theatergoers are especially attached to their nüxiaosheng. This phenomenon gives rise to new ways of understanding each other, as the real men and women in the audience are presented with idealized images of the opposite sex and can see how difficult it is to attain that ideal.

This is particularly evident with nüxiaosheng. Shaoxing opera is known for its love stories between those of great talent and those of great beauty. When women play both roles, it makes for a unique dynamic between them — one that is notably unconstrained and intimate. The sometimes-threatening dynamic of male-female actors’ relationships is replaced with a greater sense of equality, respect, and understanding for the other’s so-called female experience. This, in turn, adds nuance to the nüxiaosheng’s portrayal of idealized maleness, one that is refined, gentle, sincere, and passionate.

Chinese opera, like all art, is a way of reflecting our own desires back at us. Theatrical cross-dressing is but a dream of an ideal, forged by both actors and their audiences in a society that, even today, maintains rigid and dualistic gender views. Like any good dream, it allows us to subconsciously break down the barriers preventing us from seeing things — in this case, that pluralistic notions of gender can and do exist.

Translator: Owen Churchill; editors: Wu Haiyun and Matthew Walsh.

(Header image: A nandan prepares for a Peking opera performance in Wuxi, Jiangsu province, Jan. 23, 2011. VCG)