The Social Medium of Pen and Paper Planners

SHANGHAI — In Japanese, techo simply means “personal planner.” While some of these notebooks are painstakingly decorated, others are scrawled with notes for business meetings and household errands. But in China, techo only refers to the former — a journal maintained with loving devotion, and sometimes a touch of obsession.

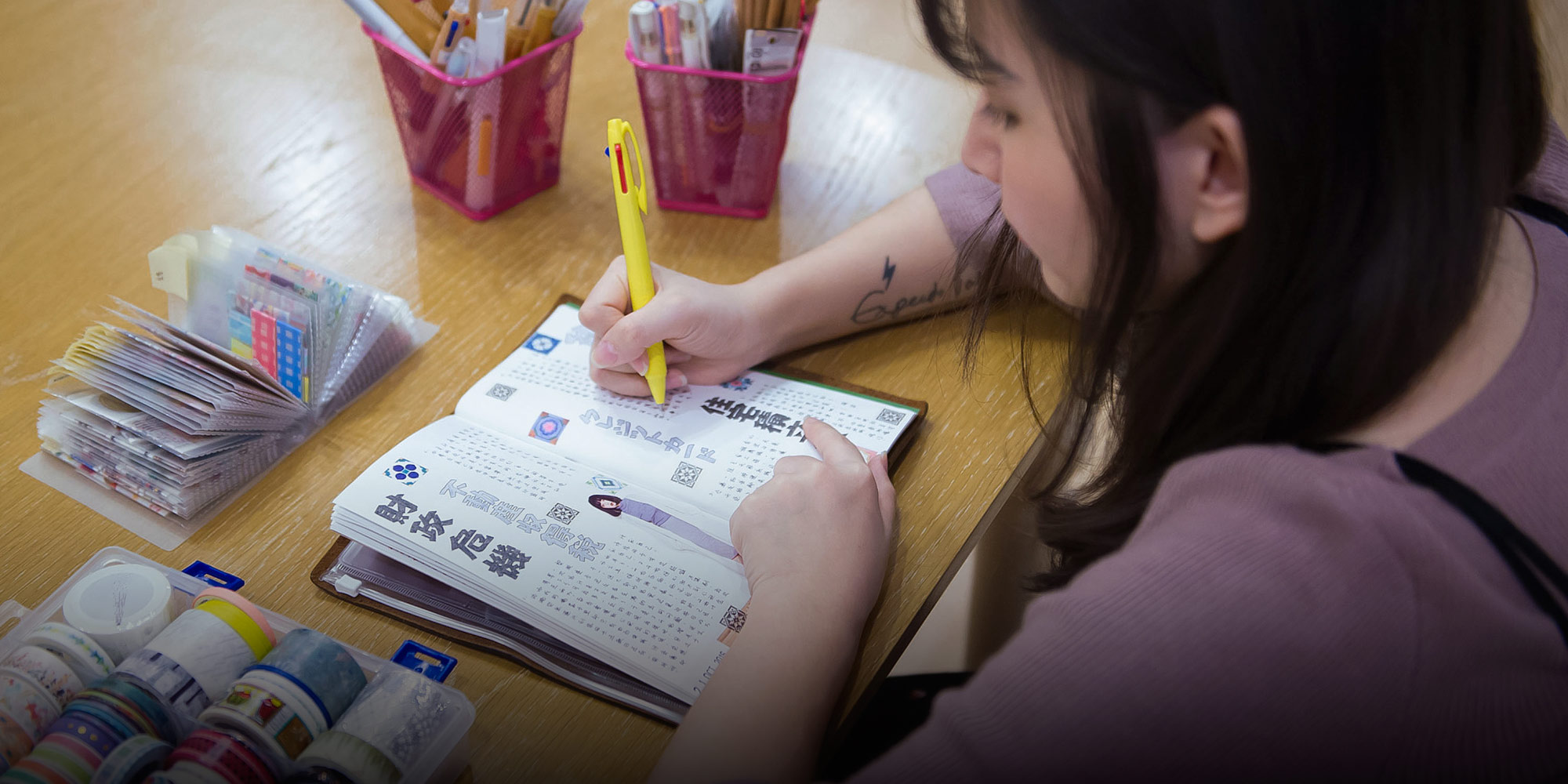

As the world becomes ever more digitized, many Chinese millennials are turning back to pen and paper to keep track of their thoughts and lives, creating their own techo — called shouzhang in Mandarin — in various styles with a combination of writing, drawing, scrapbooking, and photography. Yet the shouzhang trend also reveals the deep influences of digital culture, even on offline pursuits.

Much like Instagram feeds full of selfies and food porn, many shouzhang pages illustrate what the author ate, wore, or saw, and often pages are shared on social media. The hashtag “look at my shouzhang” has been viewed more than 1.56 billion times on Chinese microblogging platform Weibo, and shouzhang groups have popped up on online platforms like Douban, WeChat, and Weibo.

Thirty-one-year-old Yi Xiuping runs a shouzhang group that meets every month in the southern city of Shenzhen. Members have to submit daily photos of their shouzhang pages to stay in the group. “There are many who don’t last. They just act on impulse, buying many notebooks and rolls of tape, doing it for a couple of days, and then leaving it behind,” Yi says. “So, there are many newcomers, but also many being filtered out.”

As someone who has been keeping a shouzhang for more than five years, Yi takes pride in her long-term commitment to the practice, especially compared to those who just jumped aboard the latest fad. She even left her job at tech company Xunlei to start her own visual notes business — a profession in which she can readily apply her shouzhang skills.

Yi sees shouzhang as a way to relieve stress and remember the past. She shares most of her shouzhang pages on social media. The contents are not private, she explains. “It’s a way to communicate with yourself,” Yi says. “It makes your time visible.”

While everyone has their own style, Yi says most shouzhang can be divided into two categories: Western ones — which usually consist of blank pages, such as the bullet journal — and Japanese ones, which tend to be cute and decorated. Yi says her own style is more Western, focused on time management and habit-tracking — helping her eat healthy, stick to a budget, and spend quality time with her family.

Though any notebook can be used for shouzhang, the most popular brands are not cheap. One cover and set of sheets from specialized organizer manufacturers like Hobonichi, Leuchtturm, or Moleskine typically costs roughly 300 yuan ($44), while those with leather covers can fetch over 1,000 yuan ($147). Many spend much more on accessories and stationery. “I bought a box of watercolors that cost me over 800 yuan, [though] so far I haven’t been willing to use it,” Yi says. She also paid 8,800 yuan for a two-day writing workshop organized by a shouzhang network.

Japan’s Hobonichi is one of the most popular brands among Chinese shouzhang fans. According to the official Hobonichi website, more than 780,000 people around the world use the company’s shouzhang. Last year, the brand opened a WeChat shop and Weibo account to further expand into the Chinese market. And in February this year, the company organized a meet-up between select customers and its founder, 69-year-old Shigesato Itoi.

Shanghai-based business journalist Liu Yujing was one of those selected. She started keeping a shouzhang in 2014, when she was struggling with her postgraduate studies at the University of Southern California. She hoped that a shouzhang ritual would help with her personal and academic goals.

Liu believes shouzhang has brought discipline to her life. She documents her schedule meticulously, and there is an order, too, to how she keeps the book: She will never leave a page blank, and she only ever writes using a black gel pen. Yet when she looks over her first shouzhang, she concedes that she has achieved few of the plans she had detailed.

While most shouzhang-lovers are young women, there’s also the occasional outlier. For 61-year-old Zhou Rongtang, shouzhang has become an outlet for creative passions that he wasn’t able to realize in his youth, when art supplies were an unaffordable luxury. Nowadays, he fills his shouzhang with drawings of the cities he visits as an architect, and is even taking weekend painting classes so he can improve his shouzhang illustrations.

Zhou hasn’t met anyone else his age at the shouzhang events and fairs he has attended over the last two years. Most of those who keep shouzhang, he says, are teenage girls or women in their twenties. Nevertheless, inspired by the story of American folk artist Grandma Moses who famously launched her painting career when she was 78, Zhou believes that it’s never too late to start.

“There are no rules for writing or drawing in shouzhang,” Zhou tells Sixth Tone. “As long as it looks good, you are satisfied.”

Editor: Qian Jinghua.

(Header image: A woman takes notes in her ‘shouzhang’ in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, Nov. 4, 2017. Zhang Ziwang/VCG)