The Aging Hickory Nut Harvesters

ZHEJIANG, East China — Shen Ailan and her husband Xiang Chaochun stand on the branches of gently swaying hickory trees, wielding long bamboo sticks. The pair look as if they could be from the film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” — except instead of fighting, they’re knocking hickory nuts to the ground.

Shen and Xiang are among the numerous villagers in northern Zhejiang and southern Anhui provinces whose lives have been changed by Chinese hickory nuts. About 30,000 tons of the popular snack — which look and taste similar to pecan nuts — are produced annually in China. Around one-third come from Zhejiang’s Lin’an District, where about 100,000 farmers are involved in the hickory nut industry, according to the local forestry bureau.

Despite the lucrative industry, there’s a shortage of workers willing to risk life and limb. Every year, during the September harvest season, dozens of hickory nut farmers are injured or die after falling from tall trees. Just last week, a 69-year-old Lin’an farmer surnamed Zhou suffered several bone fractures and brain hemorrhaging after falling from a 3-meter-tall tree where he had been collecting nuts, local media reported. “Collecting hickory nuts is like giving birth to a child: It’s tough,” says 49-year-old Shen, referring to the exhausting and risky collection process. “If anything bad happens, you can’t recover losses [from the medical fees] no matter how many hickory nuts you sell.”

Thirty years ago, life was very different for villagers. “We didn’t have anything — no TV, no [electric] fans,” Shen says. She spent her childhood learning how to collect nuts, and didn't go beyond primary school, whereas her husband didn’t finish middle school. In her early 20s, she began learning how to climb trees — traditionally, women just collected the nuts from below — and is currently the only woman in Lin’an’s village of Wucun who’s brave and strong enough to climb the hickory nut trees, she says. Nowadays, nut farmers like her have TVs, cars, and three-story houses.

It’s now rare to see young people on the steep hills where the hickory trees grow. Most of the younger generation finish high school and head off to seek employment elsewhere. Shen and her husband, for instance, have a son who received a master’s degree who now works as an engineer in Shanghai.

To fill the labor gap, farmers like Shen must hire helpers during the harvest, though it can be hard to find workers willing to take on the exhausting and dangerous job. The price of hickory nuts fluctuates from year to year: This year, the unshelled nuts are sold at 10 yuan ($1.5) per kilogram — slightly higher than last year, but still lower than the 14 yuan per kilogram they’ve sold for in recent years. Meanwhile, the daily rate for nut collectors continues to rise. In the past, Shen and her husband have hired two or three couples to help during the harvest season, but this year, they only hired one. Xiang’s family pays 400 yuan a day to the man who has to climb trees, and 200 to the wife. By comparison, the average salary in Shanghai last year was 357 yuan a day.

During the harvest season, Shen wakes up every day at 4:30 a.m. to cook breakfast for her husband and the couple they’ve hired to help collect nuts. She prepares a dozen mooncakes, apples, and four bottles of tea. At 6 a.m., they set off for the hills, ready to start a long day of physical labor.

Almost every household in the countryside of Lin’an owns a few hundred hickory trees — Shen’s family has over 1,000. Shen, her husband and the two workers they've hired ride a motor tricycle for about 10 minutes, and then hike half an hour to the top of a hill covered by hickory trees and bamboo. Although Xiang and the male worker surnamed Li are lean, they each carry a wheelbarrow on their shoulders.

In recent years, villagers have hammered long nails into tree trunks to make it easier and safer to climb. For decades though, the way they’ve collected hickory nuts hasn’t really changed — men climb trees barehanded to knock down fruit; women and the elderly collect nuts from the ground.

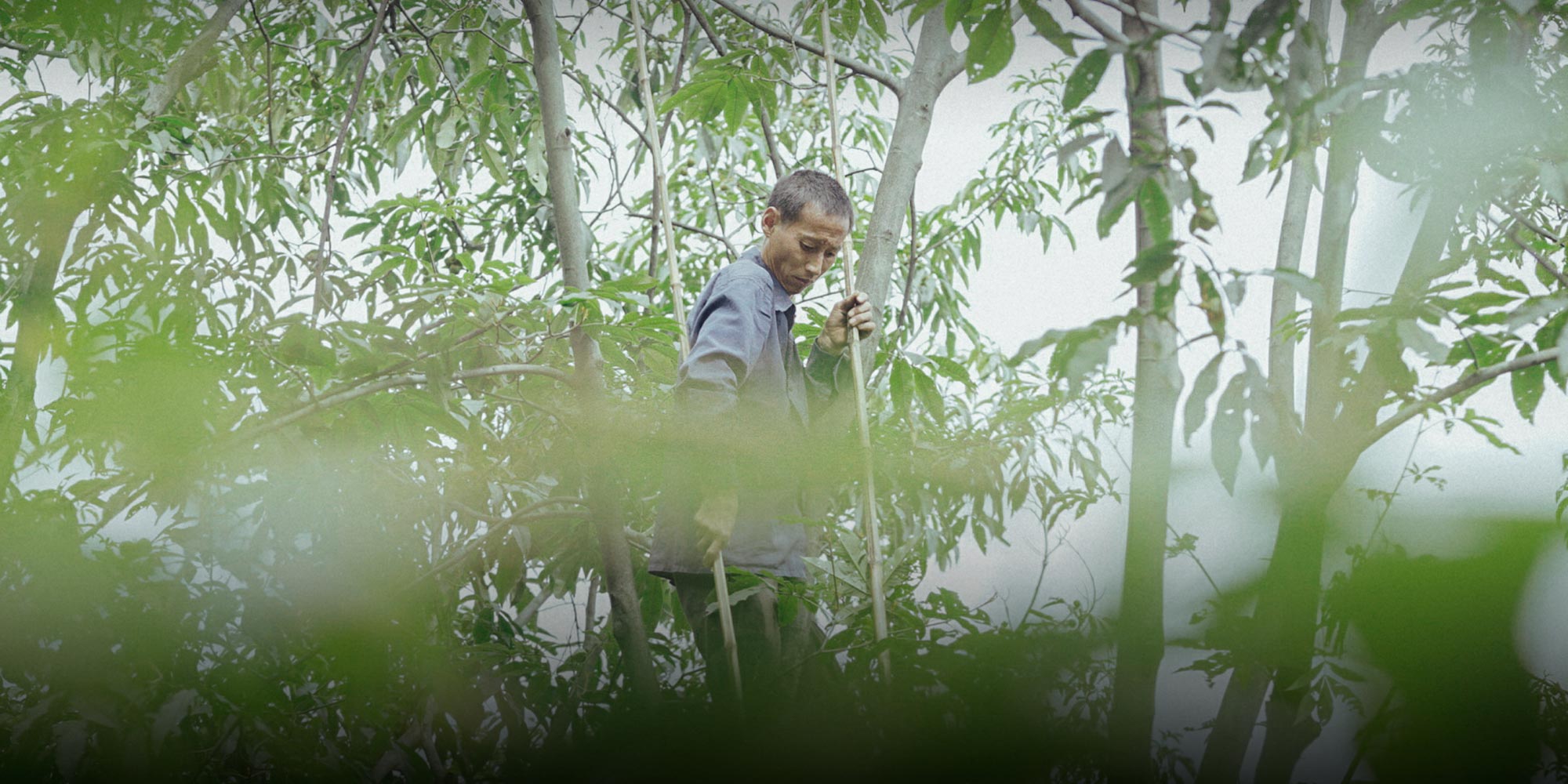

High up on the tree, Xiang stands on hickory tree branches as thin as his arm. Each time he hits the nuts with his bamboo stick, the two branches he’s standing on sway. It takes him an hour to knock all the nuts down from one big tree. He stops to eat an apple, before moving on to another tree. From time to time, the rhythmic sound of knocking wood and rustling leaves is interrupted by an “Ouch!” as the thick-husked nuts drop through the trees and onto the heads of the women below.

Despite the risks and the labor shortage, the middle-aged farmers are still fond of their hickory trees. Many still have vivid memories of families growing hickory trees together in the early 1980s during the reform and opening-up period. At the time, each household was given land and started to plant more trees.

“They feel attached to the trees — they have grown up with these trees,” says Wang Caiqiong, 35, a migrant worker from Anhui. Her family is growing new hickory trees for her 13-year-old son, who has learned how to climb. “When he grows up, he can choose not to harvest hickory nuts, but he needs to know how to do it.”

Shen and Xiang don’t know what they’ll do with their 1,000 hickory trees once they’re too old to harvest the nuts. They understand that their only son is not going to take care of them. Instead, they might just wait for the nuts to fall naturally or contract their land out to companies — but they wouldn’t get much money out of that.

For now, the couple is still strong enough to continue. At the end of a day’s work, they’ve collected around 500 kilograms of nuts in total. As Xiang carries bags of hickory nuts down the hill, he sings a popular song replaced with lyrics he rewrote:

“Ah, hickory nuts, you’re best among the nuts. Ah, hickory nuts, why must your price be cut?”

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

(Header image: A worker hired by Shen Ailan prepares to knock down hickory nuts in Wucun Village, Zhejiang province, Sept. 8, 2018. Tang Xiaolan/Sixth Tone)