How the Fabled Folk Tradition of Feng Shui Endures

JIANGXI, East China — Zhong Xihua was a young man when he first visited the underworld. On his way back from a village meeting one night in 1969, Zhong met a bearded old man wearing a robe who dragged him down into a dark well. Rather than being a trap, the well unveiled an underground world that resembled Beijing’s Forbidden City. “We walked through gate after gate, until we reached the ninth building,” Zhong recalls. “There, another old man in his 70s or 80s told me to do good and help others solve their problems.”

It’s a tall tale — one that Zhong, now 74, cannot prove or explain. Nevertheless, the story has helped solidify his status as an expert in the ancient divination practice of feng shui. Everyone in Dayu County, where Zhong lives, knows him as the “Governor of the Underworld.” On a typical day, he might use a compass and a yearly almanac of auspicious dates to calculate feng shui directions to help a family install a new door where it will bring good fortune. Mistakes could spell disaster for decades. “It would be terrible for later generations if the tomb of a family’s ancestor was facing the wrong direction,” Zhong explains.

Since ancient times, masters like Zhong have advised on where to build anything from imperial graveyards to humble cottages. However, feng shui was outlawed as a feudal superstition during the decade-long Cultural Revolution, which began in 1966. More recently, feng shui has been beset by accusations that it is at best a pseudoscience, while also enjoying a hands-off approach from the government. From Zhong’s rural hometown to China’s biggest cities, the mystical wisdoms of feng shui have survived, and are still in demand.

Last November, however, a local policy change pitted politics against tradition once more. Two cities in Jiangxi — including the one that administrates Dayu — joined a national pilot program that promotes cremations instead of burials to save land, protect the environment, and prevent people from holding overly lavish funerals. “The county government summoned coffin makers, pallbearers, Taoist priests, and feng shui masters to a meeting,” says Zhong, who attended one such meeting held by the county’s civil affairs bureau. “The Taoist priests were told not to perform funeral rituals anymore, and feng shui masters were asked not to go into mountains to find burial plots.”

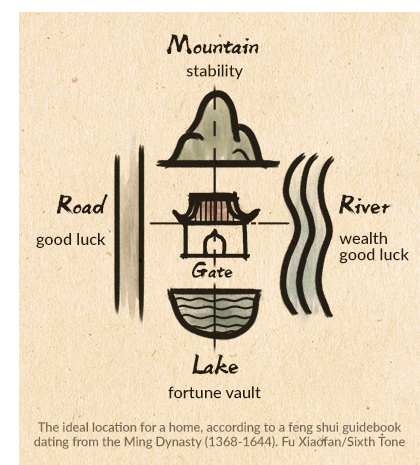

Feng shui — which literally means “wind and water” — is a loosely defined but complex mix of Chinese religion and mythology. Practitioners trace its roots all the way back to when Pangu, the mythical creator in Chinese mythology, split the earth and the sky, thereby separating yin and yang — the opposite but complementary natures of life force, or qi. Making sure that things are placed to ensure auspicious qi flow is central to feng shui. “For thousands of years, Chinese people have tried to seek luck and avoid calamity,” says anthropologist Liu Zhaorui from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou. Feng shui masters, he says, “comfort people by ascribing events and affairs to destiny and unknown powers.”

This holds true for Dayu, which is in Jiangxi’s hilly hinterland. The province’s complex landscape gave birth to a form of feng shui that relies heavily on geographic characteristics, such the direction a mountain’s ridge is going or the flow of a river’s water. It’s become a dominant school of thought in China, which has made feng shui a popular career. Liu found that in one southern Jiangxi village of about 1,200 families, there were 300 feng shui masters. For most of them, the profession had been passed down through generations. All were men: Female feng shui masters are rare, but do exist.

To ensure that death doesn’t bring the family bad luck, Dayu traditions prescribe extensive funeral processions and graves that have good feng shui. But last winter, the government began asking families to hand in all pre-purchased coffins, and said that graves of any ancestors buried too close to major roads and rivers had to be relocated to public cemeteries. While some counties in Jiangxi asked feng shui masters and other funeral-related professionals to consider changing careers, the government in Dayu enlisted Zhong and over 100 feng shui practitioners to persuade people to cooperate.

“When people came and asked me whether or not the relocation would have a bad impact on their family, I’d say it’s a government policy we should adhere to,” says Zhong. He was appointed the government’s consultant for tomb relocation and put in charge of choosing auspicious locations on public cemeteries. It was difficult to find plots whose feng shui had a long-term positive outlook. “Also, a certain direction’s feng shui changes every year, but the location of the public cemetery is fixed,” he says. “It can’t be helped.”

Sixty-one-year old feng shui master He Huabei helped families in Dayu wrap their ancestors’ remains in red cloth and relocate them to a new public-cemetery grave. Even though the campaign discredited the traditions central to his profession, he said it allowed him to make money. Also, he thought many remains had actually been moved to graves with better feng shui. Morally, however, he found it difficult to bear. “Burying the deceased is tradition,” he says. “It’s immoral to dig up ancestors’ graves. In the beginning, people could not accept it.”

Elsewhere in Jiangxi, the funeral reforms were carried out with so much force that the public pushed back. Perhaps the most infamous example of government excess occured in northeastern Jiangxi’s Yiyang County, where a recently buried body was dug up and cremated. The resulting outrage from this and other incidents impacted the entire province, and the relocation movement halted by summer.

In Hetian, a village about a two-hour drive from Dayu, it’s as if the funeral reforms never took place. In the Xiao family’s living room, the body of their 81-year-old mother lays in a wooden coffin next to a table adorned with a Taoist flag. Priest Zeng Shengming, 64, and his apprentice kneel side-by-side, chanting scriptures to the rhythm of Zeng striking a wooden fish. When they finish a chapter of scripture, three nearby musicians join in. The interwoven sounds of chanting, suona, flute, drums, and cymbals resound throughout the day.

Also a a feng shui master, Zeng had told the family that two days after their mother’s death would be an ideal burial date, according to the almanac. Today’s ritual would cleanse her sins. “The tradition in our village is that when an elder passes away, the family will invite Taoist priests to perform a ritual,” says the youngest son of the Xiao family. “It’s our wish that the deceased will have a good journey to the underworld.” During a break in the chanting, Zeng sits down, takes out a small piece of rice paper, and writes down the dates when the family would need to burn ghost money for their mother.

Unlike Zhong, who believes in the existence of the underworld and a feng shui master’s ability to interact with it, Zeng takes a more cautious view. “I’ve never been there,” he says. “Personally, I don’t think we have that ability.” There have been times when Zeng, who was born in a family of Taoist priests and started learning feng shui at age 30, doubted the tradition. “The core of feng shui is mystery,” he says. “But, after doing this for decades, I think some theories of it have been verified, because the families that have followed my advice are blessed and prosperous.” Zeng and all other feng shui masters interviewed for this article claim a 100-percent success rate.

Few scholars believe there is truth to feng shui’s heady mix of geomancy, astrology, and fatalism. Early 20th-century Dutch sinologist J.J.M. de Groot describes feng shui as “a ridiculous caricature of science” and “a mere chaos of childish absurdities and refined mysticism.” Retired geologist Tao Shilong is a present-day critic who thinks the practice is merely a beautified pseudoscience used to scam people, as he writes in a commentary for Party newspaper People’s Daily. But there are still scholars who support it. “After thousands of years of practice, feng shui has a comprehensive system that fits into contemporary science, such as geography, meterology, and psychology, despite some superstitious ideas,” Wang Qiheng, an architecture professor at Tianjin University, wrote in an article he sent to Sixth Tone.

“It might be a kind of superstition, but there are things you can’t explain,” says 42-year-old Li Yunqing, who runs a small hotel in Dayu. When she wanted to move into a new apartment this year, Li spent over 1,000 yuan ($144) to get a feng shui consultant’s advice on the location of the apartment, the position of the electric stove, the date to install a door, and the exact time she ought to cook the first meal in her new kitchen. She does not see herself as a firm feng shui believer, but when her partner cheated on her and left her, and her business did not go well, someone suggested she try talking to a feng shui consultant to improve her fortunes. “Maybe I just wanted to seek psychological relief, knowing nothing would actually change,” says Li, adding that her love life is yet to turn around.

Zhao Baoci, a 27-year-old feng shui master in Shanghai, tries to approach the practice with a critical eye. “When a client calls and asks me whether he should use his left or right leg first when he leaves his home, I’ll hang up right away. I would call this superstition,” says Zhao, who holds an economics degree from Shanghai University of International Business and Economics. “There were times when people believed that the sun revolved around the Earth and that the Earth was square-shaped,” he says. “I never blindly believe that I’m right, but the cases I’ve helped with have made me believe I’m right.”

Zhao’s main clients are businessmen and officials who need some extra luck to reach a company goal or get a promotion. “To some degree, feng shui consulting is a profession that exists because of people’s greed,” says Zhao. In a recent case, he suggested a shareholder of a publicly listed state-owned enterprise move a folding screen from behind his armchair. “There were too many bird patterns on it,” Zhao says. “It would be like people speaking ill of him behind his back.” In the near future, he plans to go to New York to work with real estate developers. The market for feng shui in the city is promising — even the golden globe standing outside the Trump International Hotel and Tower is reportedly there for feng shui reasons.

And so, the stars seem aligned for feng shui’s popularity to persist. Zhong is teaching his trade to his oldest son. “Feng shui is like my mission,” he says. Zhong seldom leaves Jiangxi on account of his old age, but he still regularly lays in his bed to communicate with the supernatural. “Every 1st and 15th of the month, I’ll go to the underworld to run errands,” he says.

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: He Huabei uses a mobile app with a digital ‘luo pan’ to quickly determine a location’s feng shui in Dayu County, Jiangxi province, Oct. 16, 2018. Fan Liya/Sixth Tone)