China’s Civil Service More Competitive Than Ever

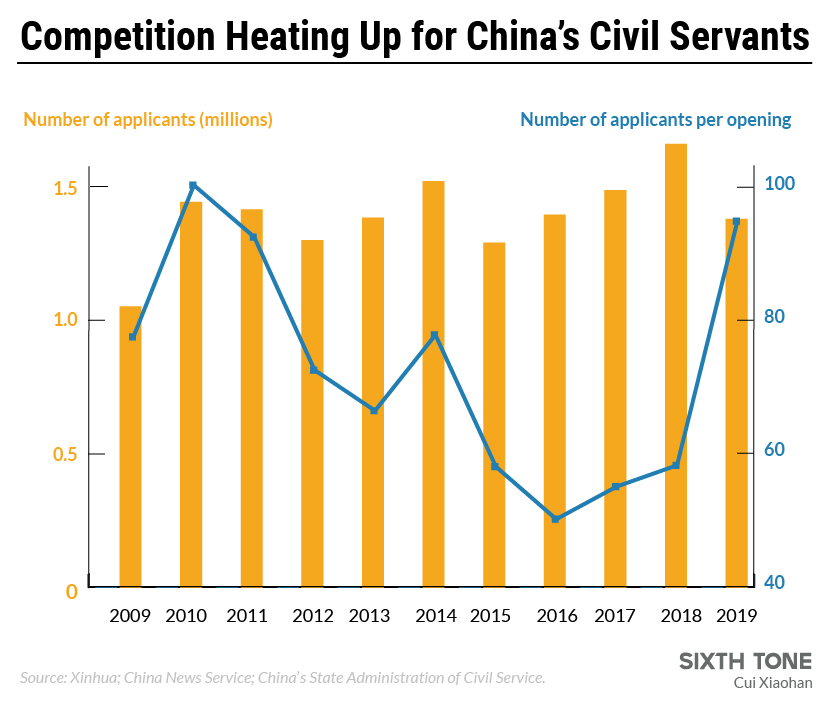

Around 920,000 people turned out to take China’s national civil service exam on Sunday, an average of 63 applicants for each open post, according to state news agency Xinhua. An additional 450,000 candidates who had been approved to sit the exam didn’t show up.

This marks the 11th consecutive year in which over 1 million people applied to take the annual exams, but the current competition is especially fierce: This year’s recruitment quota is set at just 14,500 vacant posts — around half as many as last year. Wang Yukai, a professor of public administration at the Chinese Academy of Governance, told Shanghai newspaper Wenhui Daily that the dramatic slash may have to do with March’s major cabinet reshuffling, which resulted in a net loss of over a dozen ministries and departments of the central government.

Careers in the civil service or at state-owned enterprises are often referred to as the “iron rice bowl” for providing those who obtain them with steady incomes, elevated social status, and near-certain job security. Such posts are especially coveted in China’s smaller cities, where there are fewer employment opportunities compared with first-tier cities.

“It’s the hope of my entire family,” recent university graduate Zhao Xinyu told Sixth Tone, referring to securing a job as a public servant. Zhao, a native of the eastern province of Anhui who works for a private company, was one of the 920,000 who sat the civil service exam on Sunday. Hailing from a sparsely populated county near the city of Wuhu, Zhao said his parents are nagging him to get a government job. “In rural China, being a civil servant is still the most ideal job in the eyes of the older generation,” he explained.

However, in more developed parts of China, such positions don’t hold as much luster as they did during the country’s economic boom. Xinhua reported in 2014 that a five-year civil servant in Guangdong province earned a little over 2,700 yuan (then $440) a month, in addition to receiving a year-end bonus equivalent to one month’s income and 4,000 yuan in holiday bonuses. The same year, the average monthly salaries in the province’s two largest cities, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, were 7,261 yuan and 6,830 yuan, respectively, according to a survey by the South China Market of Human Resources, a government entity administered by Guangdong’s human resources and social security authority.

After the adoption in 2012 of President Xi Jinping’s Eight-Point Regulation — comprised of policies aimed at weeding out official corruption — civil servants’ so-called gray income from “gifts” and side businesses significantly dropped, according to a 2015 report by Party-run People’s Daily. Although China’s cabinet, the State Council, announced the same year that it would adjust civil servants’ incomes by an additional 300 yuan per month on average and continue doing so at annual or biennial intervals, some civil servants nonetheless opted to give up their iron bowls.

Next year, a record 8.34 million students are projected to graduate from Chinese universities, posing a potentially severe challenge for those seeking employment within the domestic job market. In such an environment, many continue to view the civil service exam as a way out of the economic doldrums.

“It’ll be very hard for me to find a job, as my major will afford me only limited employment opportunities,” Su Xiaolei, a library science student at Soochow University, told Sixth Tone. “I see becoming a civil servant as a good choice, and I’m very attracted to its high stability.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: Civil service candidates wait outside a testing center in Nanjing, Jiangsu province, Dec. 2, 2018. VCG)