The People Paid to Hear Pillow Talk

GUIZHOU, Southwest China — On a misty October night, as the fog swallowed the bright neon lights of Guiyang’s big data zone, Liu pressed play on his computer. He listened to idle gossip about the news, awkward flirting, and tone-deaf singing to upbeat pop music — then something much more arresting.

“Ah, ah, ahhh! I can’t hold back! I want it!” a female voice shrieked, appearing to orgasm before letting out a sigh of relief. Liu’s face remained impassive. “Ban,” he decided, resolutely clicking a button on his computer.

For eight hours each shift, 21-year-old Liu puts on his headphones and listens to other people interact. He’s one of 30 content managers hired by voice-messaging social app Yuwan. The app was founded in 2015 in Guiyang, partly motivated by the local government’s big data push, and later moved its headquarters to Beijing. The content moderators, however, remained in Guiyang to save relocation and rehiring costs. Now boasting 20 million registered users, Yuwan is part of a small but growing number of voice-messaging apps that connect strangers who want to chat online.

Although the app was intended to be an innocent space to find friends, a quick glance through the chat listings reveals a burgeoning hookup culture. Some users break the app’s rules — or even the law — by sending sexually explicit messages, using profanity, spreading rumors, or harassing other users. Although the app has always required content-checkers, nowadays rule-breakers are on the rise, according to Yuwan.

That’s where Liu comes in. Yuwan relies on people like Liu — who asked not to use his full name, fearing that his parents would find out about his job — to monitor the conversations of the app’s 500,000 daily active users. If someone believes their fellow user is breaking the rules, most commonly by swearing or using sexual language, they can report them. And if Liu and his counterparts agree with the report, the offending user could find themselves banned for 24 hours or even permanently blocked.

When Liu starts work, messages are usually already waiting for him. Content moderators must process messages within two minutes of the initial report. On peak days, an individual moderator may handle up to 5,000 messages within a shift. The sheer volume means sometimes Liu must simultaneously listen to and process up to five voice messages at a time. Yuwan is organized as a series of mostly public chat rooms, in which up to nine people can talk over each other as background music plays. The app has no age restrictions, and since most chat rooms are not private, anyone could end up overhearing a person swearing or using sexual language.

The cacophony can be overwhelming for Liu, who’s been with Yuwan for almost two years. After graduating from a technical school where he majored in kindergarten education, Liu worked a stint as a China Telecom customer-service representative. Now after work, he often spends time on his own playing video games, attempting to recharge after his noisy shift.

Sometimes, he finds himself inadvertently turned on by the sexual content he overhears, or negatively affected by users’ vitriolic spats. On occasion, he’ll finish a shift with his ears still buzzing, or he’ll be easily agitated when a friend taps him on the shoulder. “I sometimes delude myself into thinking that the users are cursing me,” he said.

Content moderation is big business in China, home to the most internet users in the world — and some of the most restrictive internet policies. Circulating rumors and porn is banned, and platforms often take off, only to be flooded by obscene content and then face an inevitable strict crackdown by the authorities. Livestreaming platforms, for instance, were a popular way to meet strangers in 2016 and 2017, which led to the government tightening internet regulations. Platforms like Douyin and Kuaishou began hiring more content editors — including Communist Party members — to monitor users’ behaviors. As platforms expand, some content inevitably strays into R-rated territory, or falls foul of what the authorities might condone.

For now, voice-messaging platforms are flying under the government’s radar. Nevertheless, the platform tries to keep content clean to ensure user safety — and to avoid future government crackdowns. “The government has been stepping up policies on livestreaming since last year: We’ve seen users moving toward voice-messaging platforms,” said Chen Xiaoxiao, head of Yuwan’s content-management department. Any trend that grows too fast will inevitably attract regulator attention, she added.

While artificial intelligence is already helping moderate content on platforms like Facebook, at Yuwan, this task is given to human content moderators. AI hasn’t yet become developed enough, said Chen, adding that algorithms wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between, for example, physical exhaustion while running and heavy breathing during sex. In the future, however, AI will inevitably get good enough to take over content-moderating jobs, she said. Chen prefers to hire female staff, believing that men may become sexually aroused if they have to listen to sexually explicit messages each day. Despite her hiring preference, Yuwan has fairly even numbers of male and female content managers.

Wu, who’s considered Yuwan’s star moderator, believes she has the necessary attributes: thick skin and a detective’s intuition. Content moderators earn 6,000 yuan ($870) a month — higher than the average 5,560-yuan wage in Guiyang — but their pay may be docked if they penalize an innocent user or if they miss an offending one. But in the last two years, Wu’s never made a mistake.

The 24-year-old started working at Yuwan three years ago, after working a series of odd jobs. The transition made sense: She’s been using voice-messaging apps herself for years, and still uses them even now. She first used them to find e-sports and online gaming teammates, and then as a way to make friends. Yuwan’s demographic is 18- to 25-year-olds, and Wu thinks that, like her, many are looking for unique, close friendships. “If [your secrets are] something that you won’t even tell your closest friend, you’ll probably confess it to a stranger online, simply because no one knows who you are,” Wu said. “Even if they judge you, you won’t care.”

While playing on the apps, she noticed guys who were constantly harassing girls and even experienced some of the harassment herself. When she came across the Yuwan job, she was excited: It was a chance to help keep Yuwan a safe space in which people could talk about their thoughts, rather than letting the platform slip into violence and cyber-orgies. “I’m like the online police, only with less power,” Wu quipped.

When Wu first started the job, she found it hard to listen to orgasms and colorful language day in, day out. She had trouble sleeping, and when she did drift off, the sounds of men moaning and grunting still played in her head. Like her fellow workmates, she’s dealt with the stress by talking with her workmates over dinner about the weird stuff she’d heard that day or taking her mind off it altogether by reading. She’s still disgusted when she hears sexual interactions between a man and a woman, although she doesn’t mind overhearing sexual interactions between two men, because she thinks they’re usually just joking around. “When it’s a woman and a man, you can tell they’re really trying to have phone sex, but if it’s two men, they just seem like they’re just kidding,” Wu said. When asked how the company was taking care of its staff psychologically, Chen said the company was looking into hiring an in-house counselor.

Wu now finds the job easier to deal with. She enjoys the powerful God’s-eye-view of her role, even if she still has to look at salacious pictures and listen to sexual sounds. And Wu’s become adept at telling when people are swearing, even if they’re using a dialect she doesn’t understand to avoid detection. As a result, she’s learned curse words in several dialects. “Some might think these arguments are horrible to listen to, but I just see them as jokes,” Wu said.

Nevertheless, Wu doesn’t want to be a content moderator forever. One day, she’d like to become a social app designer herself — after all, it’s an area in which she’s very experienced. “We [content moderators] are the closest to the users; we know what they want,” she said.

Editor: Julia Hollingsworth.

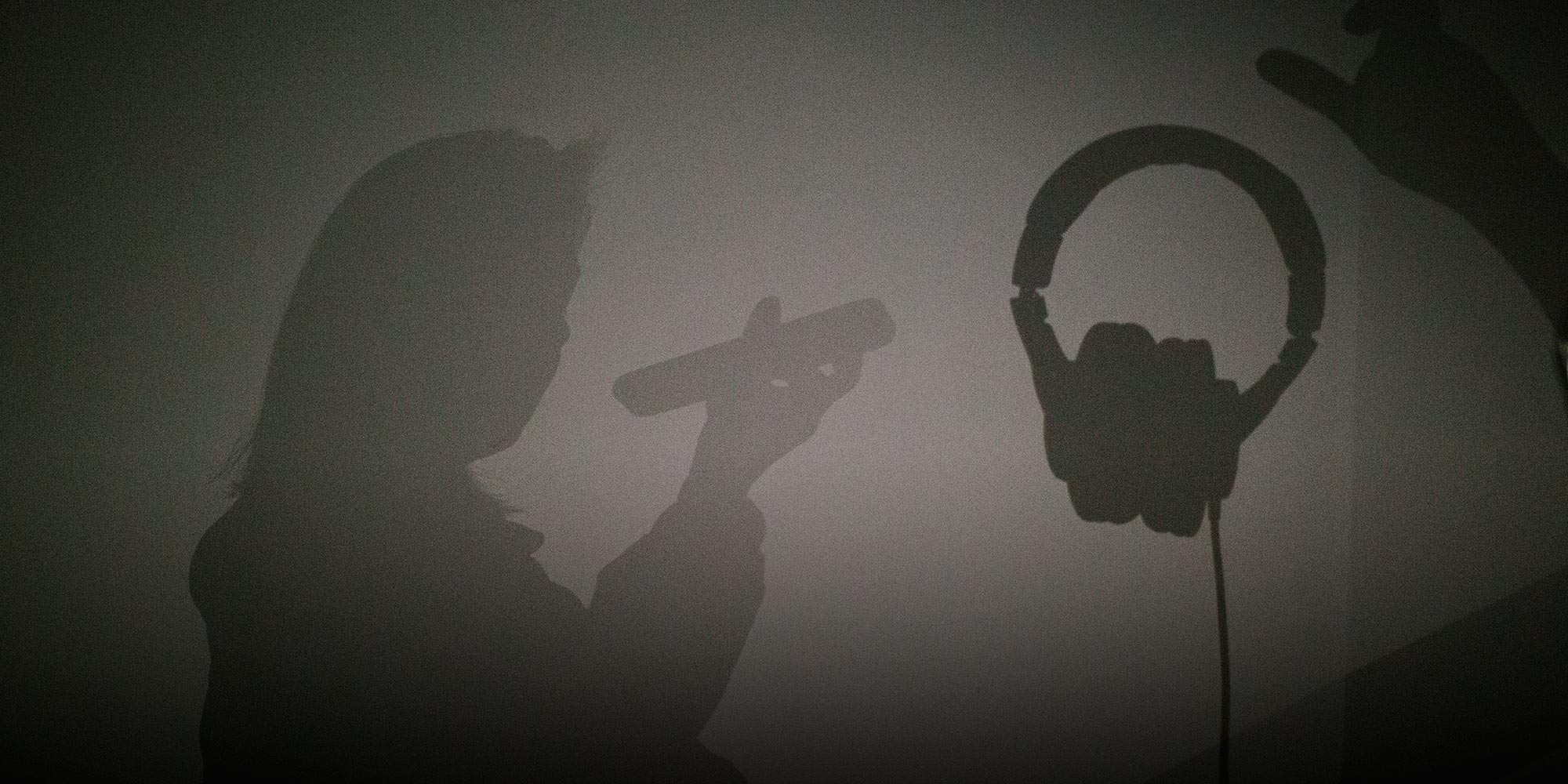

(Header image: Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone)