How ‘Wangban’ Can Shrink China’s Education Gap

This article is the first in a two-part series on ‘wangban,’ a controversial academic livestreaming model aimed at reducing educational inequality.

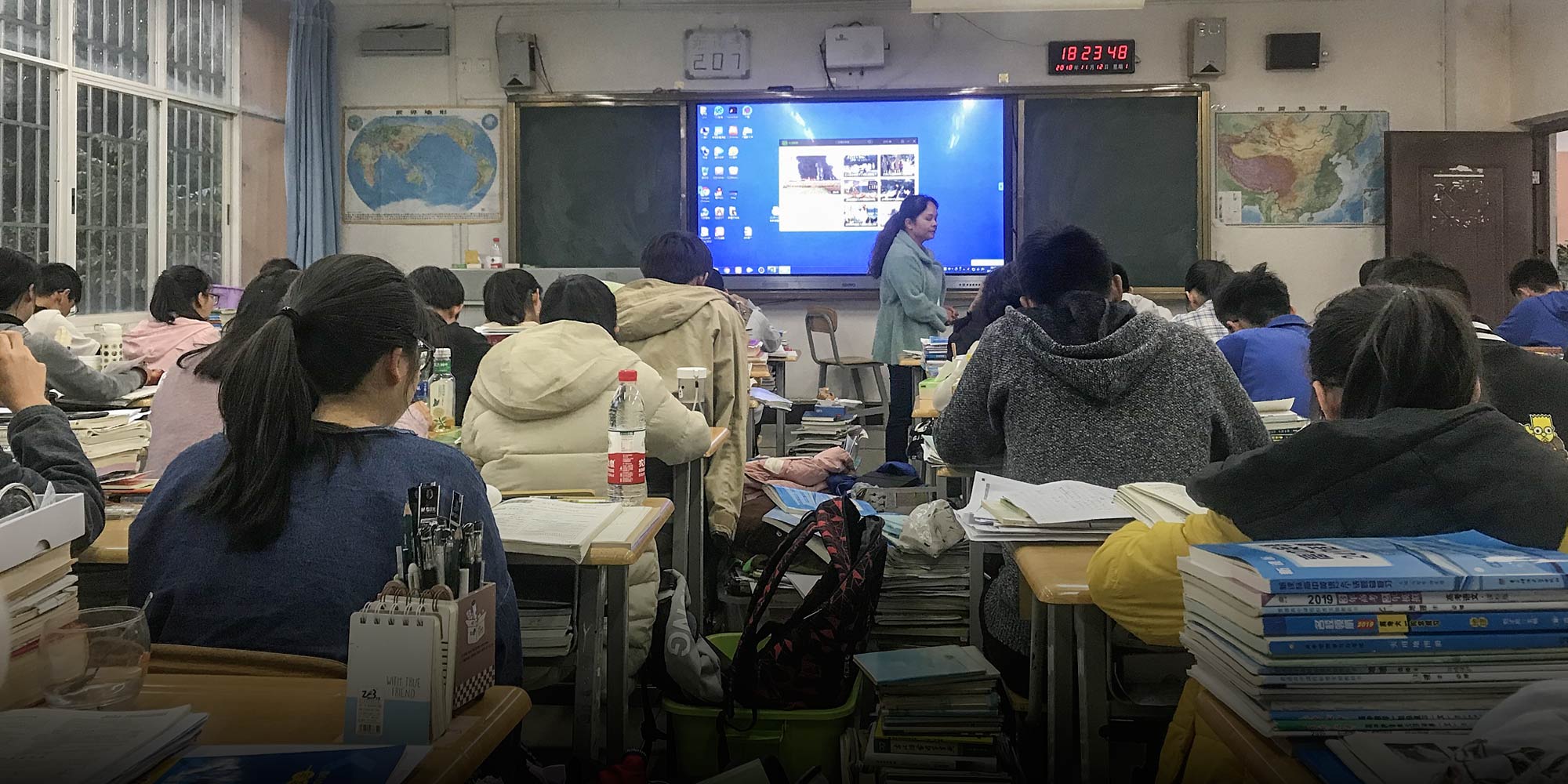

Last week, a China Youth Daily report heralding the growing popularity of so-called wangban classes in the country’s secondary schools sparked a nationwide debate. Titled “This Screen May Change Your Life,” the report centered on students like those at Luquan No. 1 Middle School, located in an impoverished corner of the southwestern province of Yunnan. Participants in the school’s wangban program use livestreaming technology to remotely attend classes at Chengdu No. 7 Middle School, arguably the best secondary school in all of southwest China.

Educational inequality is a severe problem in China, where scarce resources always seem to flow inordinately toward top schools in major urban areas, and I, for one, believe we should encourage anyone willing and able to bring the benefits of a better education to students in impoverished areas. Yet, media outlets and independent bloggers all over the country seem intent on denouncing the program for what it isn’t, rather than applauding it for what it is.

As a primary-school teacher myself, I know full well that the report glossed over some significant problems with the wangban model, but that doesn’t mean we should allow the program’s flaws to overshadow its many virtues.

One of the most common criticisms lobbed at wangban classes is that their success rate is too low. According to the abovementioned report, in the 16 years that Chengdu No. 7 has offered wangban courses, 72,000 students from 248 secondary schools — many located in poor parts of the country — have partaken. Of these, just 88 tested into Tsinghua or Peking University. That’s an average of 0.35 students per school. For context, more than 70 students from Chengdu No. 7 got into those two schools last year alone.

Others criticize wangban for exacerbating the problem of educational inequality. Slots in wangban classes are generally reserved for a small number of star pupils in participating schools, and school administrators — who yearn to see such programs succeed — typically allocate their best teachers to these classes. This sometimes ends up aggravating educational inequality within resource-poor schools, as the gap between the best students and everyone else grows wider.

Another widespread claim is that wangban contribute to the bootcamp-like atmosphere at many Chinese secondary schools. Wangban students have almost no spare time, since they’re expected to keep up with students at one of the best schools in the country. Buried under mountains of coursework, some wangban students complain of being overworked and overstressed.

Instead of investing in wangban, many commentators argue, our goal should be to encourage educational equality through systemic reform. Only then will children from underdeveloped regions be guaranteed the benefits of a first-rate education.

That’s a noble goal, but as a teacher, I must wonder how many of these critics have any real-life teaching experience. How familiar are they with the state of education in China’s impoverished regions? They obviously know there’s a huge resource gap between urban and rural schools, but do they understand how this plays out in practice?

In the high-minded words of one commentator: “The notion that a screen could change your life is based on a belief that the chief problem in impoverished areas is poor-quality teachers, when in reality, there’s more to it than that.” I had to stifle a laugh as I read through their argument. What does this person know about “reality”?

I’m a teacher at a primary school in a prosperous southeastern town, located right where the city meets the countryside. Because our county is one of the most affluent in the country, and because officials here value education, our school is in decent shape. And yet, when it comes to teaching resources — or any kind of resources — we’re at the bottom of the food chain.

Each year, the county’s so-called experimental primary schools receive first pick of the best equipment and staff, followed by the “central” primary schools, and, only then, semi-urban or rural schools like mine. Whereas experimental primary schools are staffed by the best teachers the county has to offer and have money for foreign teachers and extracurriculars, at my school, we’re so understaffed that music and gym instructors are teaching Chinese and math. Watching them muddle their ways through spelling lessons in front of a class of impressionable primary schoolers is heartbreaking. And when we do manage to hire a good teacher, they’re quickly poached by a school higher up the line — even I’ve received offers to move up.

And bear in mind, this is at a well-funded school system in one of the country’s richest counties. If, even here, the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer, you can only imagine what the situation is like elsewhere.

If those criticizing wangban truly understood “reality,” they wouldn’t be so haughtily dismissive of on-the-ground efforts to address this problem and give rural students a chance to learn from proven teachers.

I admit, wangban are far from perfect. It’s fair to question if local teachers and students can keep up with instruction, whether limiting enrollment to top students may actually increase inequality, or if there’s a way to run them that isn’t tantamount to academic force-feeding. But the real question we must answer is whether we should encourage efforts to bring about change, even if they’re imperfect.

I say we should.

Commentators like to talk about the importance of educational equality, and they’re not wrong. The question is: How do we get to that point? Too often, advocates are detached from reality. Rome wasn’t built in a day, and reforming China’s educational system will take time. As nice as their words may sound in an essay, their arguments do little to actually advance reform. Sometimes, compromise is necessary. In areas with limited resources, that might mean helping top students first, or asking motivated students to sacrifice their work-life balance for a few years for a chance at a better future.

I myself attended a strict, workload-heavy high school, and I’m thankful for it. If I hadn’t had that experience, I doubt I’d be in a position today to fight for greater equality for the next generation. That doesn’t mean there aren’t ways the wangban program could be improved. Perhaps the classes could be divided, not according to test scores alone, but according to student interest and motivation. And if the model proves itself, the country should look for ways to eliminate the financial and technical obstacles that stand in the way of wider adoption.

The internet cannot fix all our problems, and reducing educational inequality will require a long-term program of planning and investment. But, as with all things, difficult problems cannot be solved through high-minded slogans or keyboard activism alone. Real solutions will require us to compromise, to make hard decisions, and perhaps to even take risks on unproven technology. The wangban model has potential, so I’d ask the country’s commentators to give it some time. In a few years, who knows? Perhaps it will have blossomed into something wonderful.

This article was first published on the WeChat public account Narada Insights and has been condensed and republished here with permission. The original can be found here.

Translator: William Langley; editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Students take part in a livestreamed class at Luquan No. 1 Middle School in Kunming, Yunnan province, Nov. 12, 2018. VCG)