China Can’t Livestream Its Way to Educational Equality

This article is the second in a two-part series on ‘wangban,’ a controversial academic livestreaming model aimed at reducing educational inequality. The first article can be found here.

The first time I heard the term “wangban” was in 2013, during the summer between middle and high school. Representatives from my local high school came to pitch us the idea. “You’ll be taught by teachers from Chengdu No. 7 Middle School,” they told us, referring to arguably the most well-regarded comprehensive secondary school in southwestern China.

I spent the whole summer bouncing between excitement and awe. To those of us who had been force-fed a dream that, one day, we could change our lives by testing into a top university — but who’d gradually realized that we’d never be able to do so — the class represented hope. It was a second chance for second-tier students like me.

In China, educational resources have long been concentrated in urban areas, and within those, at a few so-called key schools. And Chengdu No. 7 is among the best of the best: It’s so good at getting graduates into top universities, it’s become a household name in China. According to a recent China Youth Daily article, more than 70 Chengdu No. 7 students tested into Peking University or Tsinghua last year. What gets glossed over, however, are the ways some of Chengdu’s other, less prestigious schools have bent themselves out of shape trying to keep up with their better-funded peers, or how students at these less selective institutions feel when they realize that the name on their high school uniforms brands them as inferior.

My school had never offered a wangban class before my freshman year. Slots were allocated based on test scores, and competition was fierce. It was a grand experiment, and the results didn’t disappoint: Over 90 percent of wangban students got into a first-tier university. I wasn’t one of them.

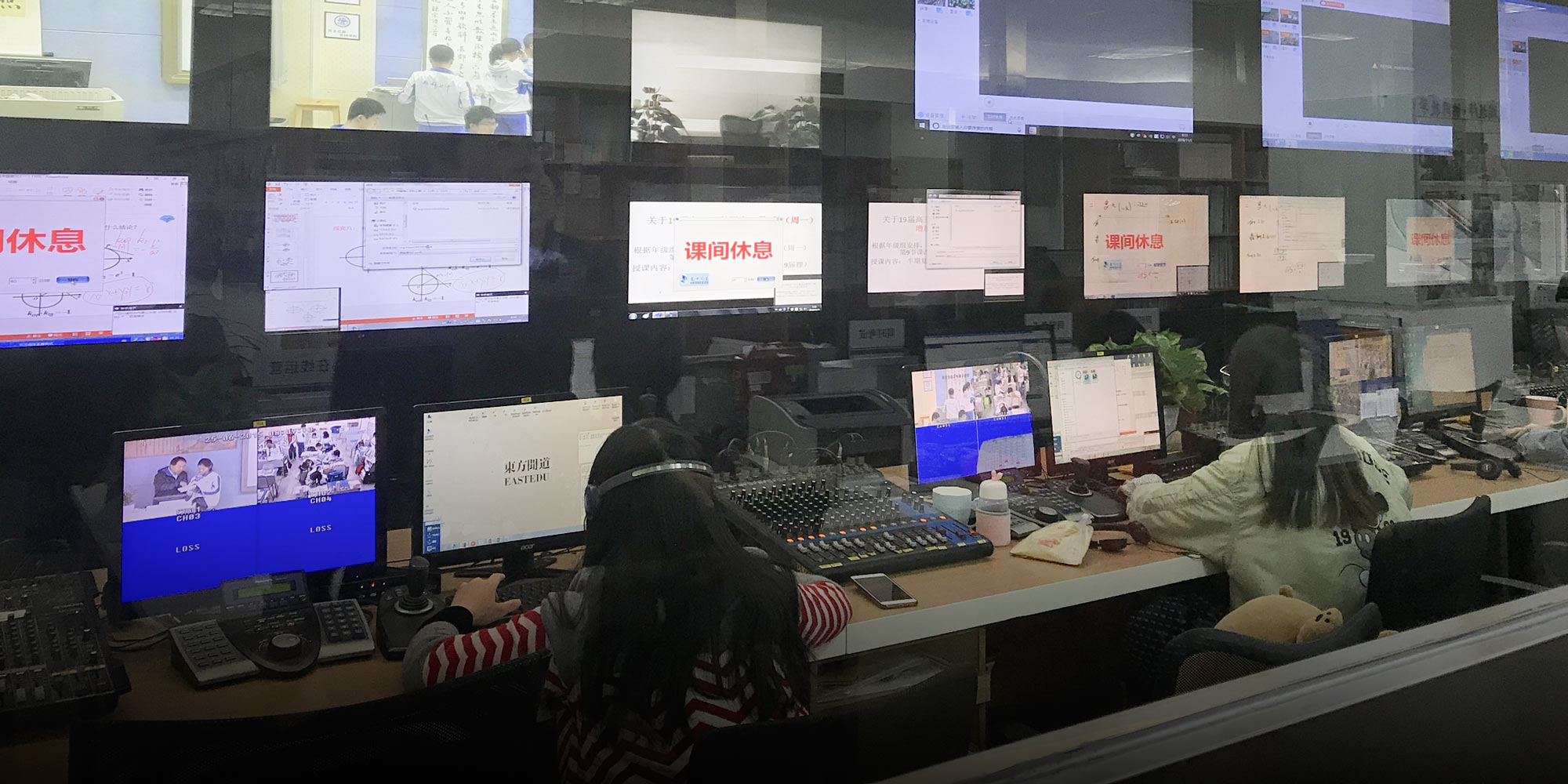

Wangban courses are conducted through a livestreaming platform that connects students from around China to classrooms at top schools like Chengdu No. 7. Every day, we would watch remotely as some of the best teachers in the country taught some of the best students in the country. All class sessions were recorded, and teachers or students were free to copy them, either for class or to review on their own.

Objectively speaking, wangban are a reasonable and even innovative solution to some of the problems facing China’s education system. Not only do they offer schools and students in poorer areas access to some of the best educational resources China has to offer, they also let them see how No. 7 teachers and students approach their work. But in my experience, however, the model’s implementation was so muddled that it undermined much of its merit.

To begin with, the logical outcome of the wangban model, at least at my school, was that it doubled the amount of work we had. That meant twice the courses, twice the homework, and twice the tests.

It didn’t have to be this way. Our teachers could have chosen to set aside their own lesson plans, or even No. 7’s lesson plans, but doing so would have required them to set aside their pride as educators. Instead, to make up for the fact that No. 7’s courses were taking up our regular class time — and thus depriving teachers of the chance to teach how they wanted to teach — the school turned our music, P.E., and art classes over to our Chinese and math teachers so they could run us through the same material again.

I still find it hard to articulate how stressful this was. The problem wasn’t so much the workload, as much as the baffling set of decisions that led to it. As the work piled up, school staff only grew more fanatical. The online classes may have been an experiment, but we soon realized they weren’t going to be allowed to fail.

I transferred out of the wangban and into a so-called ordinary class during the spring semester of my second year. Strictly speaking, it wasn’t because I couldn’t handle the pressure, but because I just didn’t see the point anymore. I remember thinking: Life is short; why waste more time doing something that’s not for me in a place I hate? Maybe I wasn’t cut out for a concentration in sciences — at our school, only students who selected this focus were eligible to enroll in wangban — but I think it had more to do with not wanting to be treated like a science experiment myself.

The wangban class was like a window to a whole new world. It let you watch everything the denizens of that world did, and it made it possible to imagine how happy you’d be, if only you lived there. But, in the end, it never let you cross through. Sooner or later, you always had to return to reality, and reality always told you the same thing: “You don’t belong.”

Our teachers constantly reminded us that the opportunity to attend class with students from Chengdu No. 7 was an honor — one for which the school had paid dearly. But, why should we see this as an honor? Why should we be thrilled to be treated like lab rats for an underdeveloped education model? Why should we be forced to acknowledge our inferiority and the inferiority of our school? Why should we accept second billing in a warped, test-centric system, where our grades are the sole measures of our value and potential?

While, ultimately, most wangban students did make it into a good school, the other six classes’ results were disappointing. This shouldn’t have come as a surprise: The wangban classes quickly became school resource-magnets. They got the best teachers, the best curricula, and the best part of the school’s attention.

To give an example of how this played out in practice, during our first year, the school purchased four air conditioning units and installed all four of them in the two wangban classrooms. The other classes had to wait until the following year.

Our teachers never let us forget just how much money they were spending on the online courses, either. I think this was meant to encourage us; but, if that was the case, their methods failed to do so. That’s because they approached everything from the school’s perspective, not from that of the students.

I asked a former classmate of mine who stuck with the class for his thoughts on the matter. Although he tested into a good school, he was realistic about the utility of Chengdu No. 7’s teaching methods at a high school like ours. “Their target is to be the best, but how many can be the best?” he asked. “Our goals are different from theirs.”

The truth is, even our highest scorers would have just been average in a typical Chengdu No. 7 class. The best students in my year got into schools like Dalian Medical University, China University of Geosciences, and the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China — good schools, but not Tsinghua or Peking University.

In short, we need to face the fact that the wangban model has not been successful. Perhaps it helped a little, but not nearly enough to justify how hard the students work and how crazy it seems to make teachers. My classmates and I found ourselves turned into hapless participants in an educational experiment, but is that really the only way forward?

This article was first published on the WeChat public account Narada Insights and has been condensed and republished here with permission. The original can be found here.

Translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Kilian O’Donnell

(Header image: A control center run by educational livestreaming company Eastedu in Chengdu, Sichuan province, Nov. 5, 2018. VCG)