Opening Up the History of China’s ‘Reform Pioneers’

This article is part of Sixth Tone’s ongoing coverage of the 40th anniversary of China's ‘reform and opening-up.’ The other articles in the series can be found here.

China’s recently announced list of “reform pioneers” — 100 individuals deemed by the government to have made “outstanding contributions” during the country’s reform and opening-up period — is a veritable who’s who of influential Chinese. Headlined by well-known figures ranging from tech mogul Jack Ma to basketball player Yao Ming, the list was compiled as part of China’s ongoing campaign to promote and commemorate the 40th anniversary of the reform.

Yet, while everyone on the list had a significant impact on contemporary China, not all of their stories had happy endings, and some have largely been forgotten. To an extent, the list’s gauzy nostalgia obscures a simple truth: Reform is a messy process, and the progress we’ve made could all too easily be reversed if we waver or forget the lessons of the past. It’s important, therefore, to look beyond surface-level hagiography and delve deeper into the complex, sometimes disheartening stories of those who made the list — and made China what it is today.

Prior to the reform period, engaging in private enterprise was a risky proposition. This was especially true during the late 1960s and early ’70s, when, amidst the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, the country’s authorities equated any private commercial activity with “taking the capitalist road” and classified entrepreneurs as enemies of the people.

That didn’t stop some from trying, however. In the early ’60s, “reform pioneer” Zheng Juxuan opened a stand on Hanzheng Street, one of the main commercial drags in the central city of Wuhan. But after 1966, China’s already meager private economic activity came under attack, and businesses that weren’t state-run were shuttered. Rather than close up shop, Zheng — who had been left nearly blind by a childhood case of smallpox — began hawking his wares from a series of inconspicuous stalls he set up along the road. For much of the next decade, Zheng played a game of cat and mouse with law enforcement officials, and his goods were frequently confiscated.

In the spring of 1978 — just months prior to the advent of the reform period — Zheng was finally sent to prison on charges of “profiteering.” While inside, he refused to divulge the names of his suppliers or buyers. This, combined with his poor eyesight, earned him the moniker the Blind Knight. Zheng was only able to secure his release in June of the following year.

By September 1979, Wuhan’s government was attempting to restart its markets after years of inactivity, in line with the recent dictates from the central government that nixed many state monopolies by encouraging capitalist entrepreneurship. The city granted Zheng and about 100 other city residents personal business licenses — the first ones it had issued in the post-Mao era. Zheng’s reputation as the Blind Knight proved highly valuable in those early, hesitant days of reform. Within five years, he had become one of the richest men on the newly revitalized Hanzheng Street.

But Zheng still bore scars from the suffering of the past. Once, when a French journalist on a press tour asked him how much money he’d made, he froze. Sweating profusely and surrounded by local government officials, he didn’t know how to respond. He worried that if he gave too high a number, he might be investigated; too low, and he would lose face — both for himself and the reform movement as a whole.

Eventually, Zheng found himself overtaken by the pace of reform. In 1992, after former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping's “southern tour” kicked off another wave of marketization, Zheng decided to open a department store. He chose a building and renovated it, but months later it was knocked down and the site redeveloped. He quickly tried again, but in 1993 that building, too, was torn down. Both times, Zheng incurred heavy losses, and he retired just a few years later.

It was an unfortunate end for a “reform pioneer,” but Zheng at least kept his reputation intact. Others included on the 40th anniversary list met with fates even more bleak.

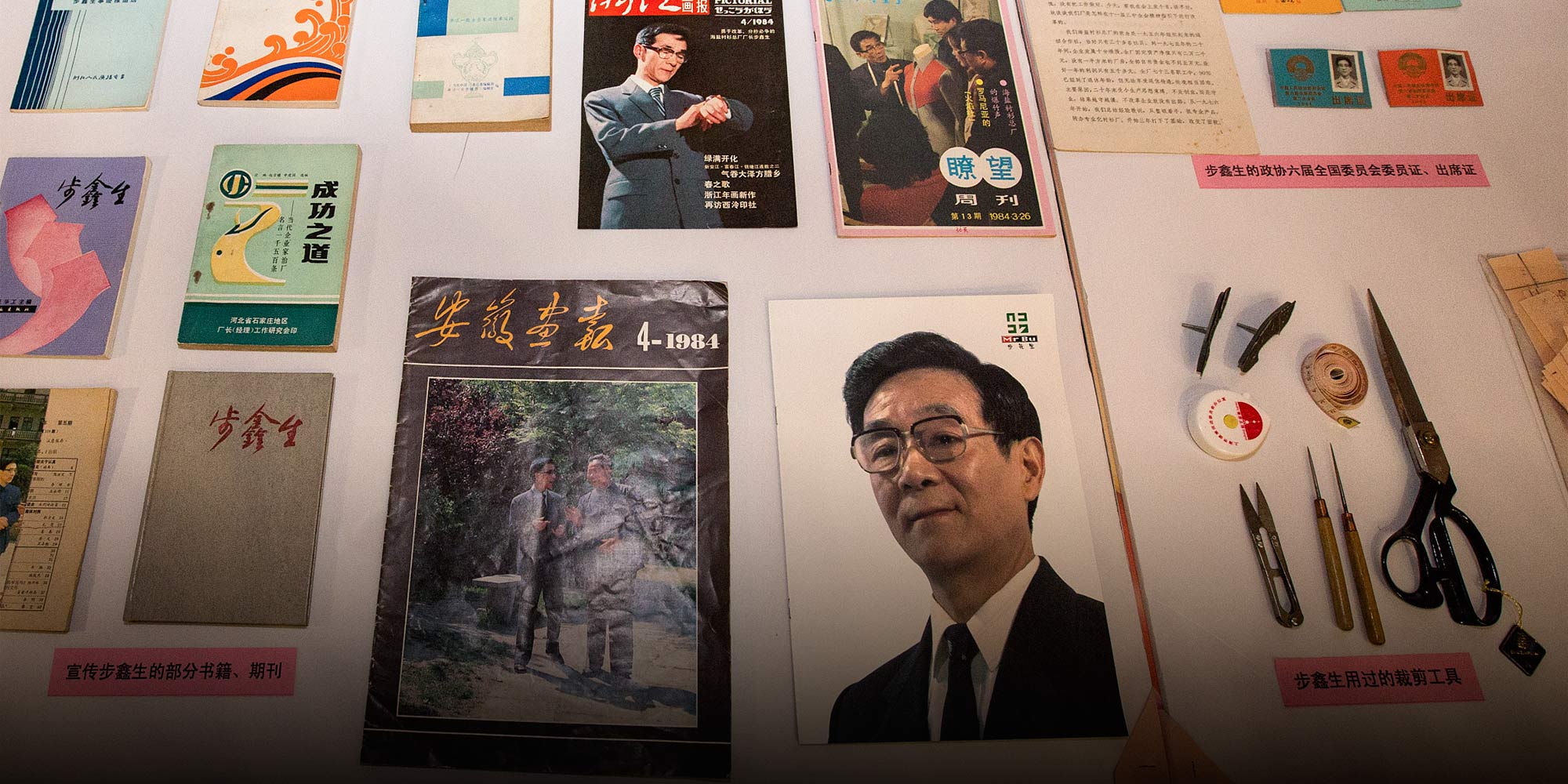

In 1981, three years after the formal start of the reform and opening-up period, Bu Xinsheng was named the new director of the Zhejiang Haiyan Shirt Factory in eastern China. Bu was a die-hard reformer, and he quickly moved to dismantle the old factory work system. He began by abolishing the practice of “eating at the communal pot,” according to which all employees received an equal share of factory profits, regardless of the amount of work done. Instead, each worker was expected to iron 90 shirts a day. Those who did more were eligible for bonuses, while those who did less were subject to salary deductions.

Output increased considerably, and Bu became a sensation. He was invited by factories, schools, and government ministries to come and give talks, and government and business representatives from all over the country flocked to Zhejiang Haiyan to study his system. On the evening of Feb. 26, 1984, the country’s state-run national evening news program ran a short item announcing that the Central Committee of the Communist Party had declared that Bu Xinsheng represented “the spirit of reform.”

Over the next month, the state-owned Xinhua News Agency published 27 articles about Bu. At age 50, he had reached the peak of his career. He couldn’t have imagined that he would soon be brought down by some of the same forces that had lifted him up.

In the early ’80s, Western-style suits had exploded in popularity across China. Shortly thereafter, in 1984, just as Bu was at the peak of his popularity, a local county official asked him to set up a production line with an annual output of 30,000 suits. Bu was concerned about ramping up production so fast, but he had little choice. Soon afterward , the official upped the target from 30,000 to 60,000.

Reports about the factory expansion eventually reached the desk of the provincial government. The relevant provincial officials decided that a national paragon like Bu Xinsheng should have no problem scaling up even further. Soon, the Zhejiang Haiyan Shirt Factory was investing in a massive expansion of its production lines, one that would allow it to produce 300,000 suits a year.

China’s suit fad passed as quickly as it had come, however. In 1986, the province — worried about falling demand — ordered construction of the new production lines be halted, but Bu stubbornly insisted he be given more time. By the time the two sides settled their dispute in 1987, it was too late: The factory was drowning in debt.

In January 1988, Bu was fired. His name once again appeared in the pages of China’s state-owned media, but this time the text read quite differently: “Bu Xinsheng dismissed from post because of brutishness, arbitrariness, and not following advice. Debt-ridden Haiyan Shirt Factory recruiting operators.”

The myth of Bu Xinsheng was shattered. He refused reassignment and left the county. Dying in 2015, he went to his grave maintaining that he had been scapegoated for government meddling in the business sector.

To reform is a choice, and stories like Zheng’s and Bu’s have much to tell us about what those choices look like. It’s important to commemorate the past 40 years along China’s road to prosperity, but we shouldn’t use that as an excuse to ignore the bumps along the way — or the brave, sometimes doomed reformers who helped get us to where we are now.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Lu Hua and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: Bu Xinsheng’s personal effects on display in an exhibition in Haiyan County, Zhejiang province, June 12, 2014. VCG)