My Life as an AIDS Nurse at a Shanghai Hospital

Even within the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center, my department is known as an island.

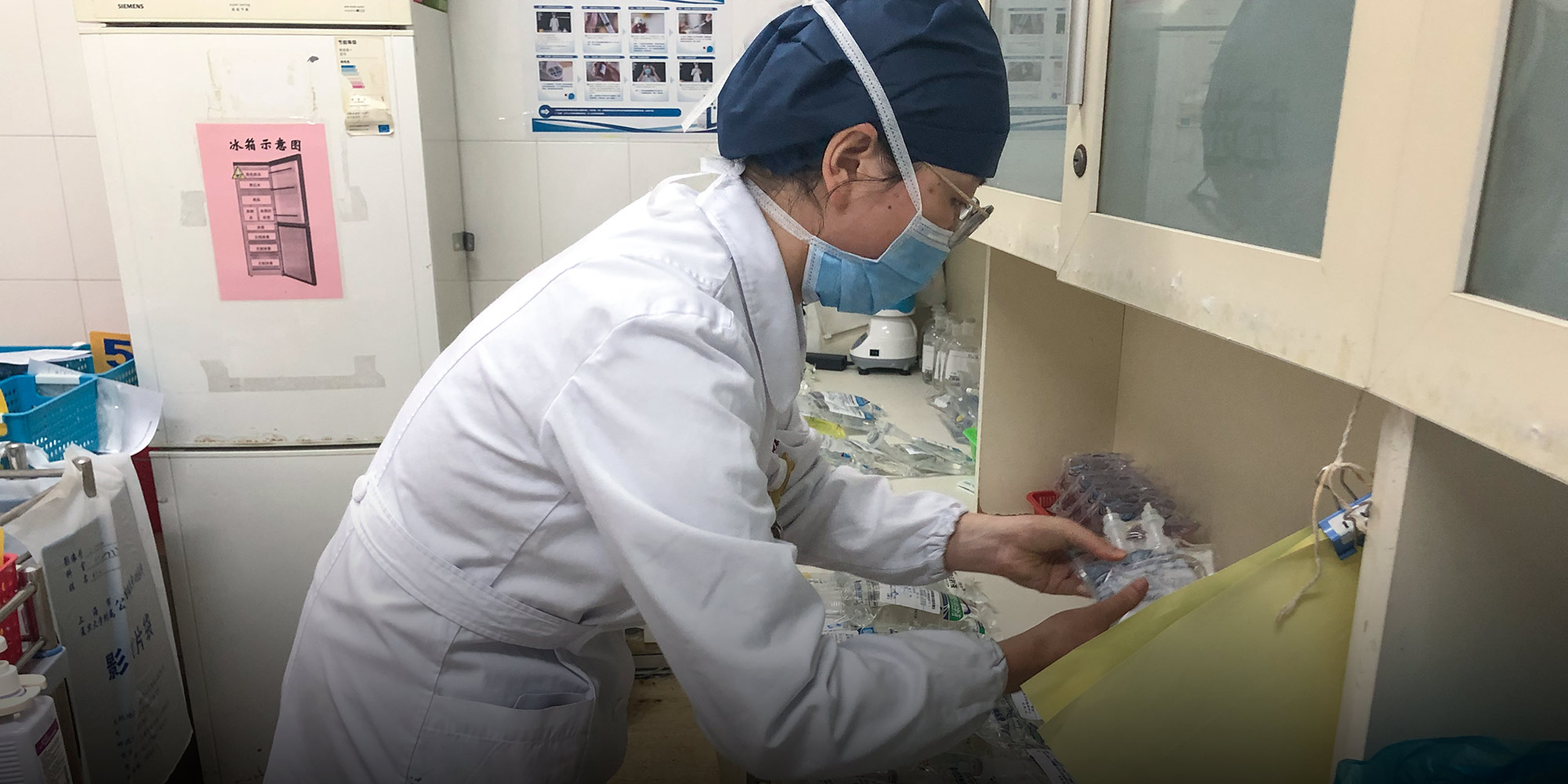

That’s because we’re one of the only medical departments in the city dedicated to the treatment of HIV and AIDS. In many Chinese hospitals, HIV and AIDS remain heavily stigmatized, and while my coworkers are generally knowledgeable enough about the condition to not fear it, many of them still blanch at the workload involved: In a single shift, a nurse in our department might need to change anywhere between 60 and 80 IV bags, all while dealing with the emotional needs and fears of patients and their family members. Although our nursing team has grown from 13 when I started in 2013 to 25 today, we still have our hands full taking care of the over 1,000 patients that pass through our doors every year.

To be honest, I never dreamed of becoming a nurse, let alone one who worked closely with HIV carriers and AIDS patients. Many nurses in China don’t have a university degree, and at the time the profession seemed both physically demanding and lacking in any societal status. Even as a nursing student at Chongqing Medical University in southwestern China, I always thought I’d try and become an accountant or civil servant after graduation. It wasn’t until my third year, when I realized the impact nurses could have on people’s health and lifestyles, that I began to see it as a potential career. I finally saw that there was more to the job than merely giving injections, changing IVs, and handing out medicine.

It was a coincidence that I ended up in Shanghai, but even in the beginning, I had no compunctions about nursing patients who were HIV-positive. Almost immediately, I was struck by how lonely these people were — many patients and their loved ones had no one with whom they could talk or share their pain. Once, after spending the night caring for a young, terminally ill patient, I was approached by his boyfriend. The young man told me all about how they’d met, fallen in love, and worked to build a better life together — they’d even briefly lived apart when he moved to a Northern European country where same-sex marriage is legal, in hopes of getting a green card.

I was a complete stranger to him. How desperate and lonely must someone be to pour his heart out to a person he barely knows? Not long afterward, the patient’s family removed him from the hospital so he could end his life at home.

Although doing so went against hospital rules, I looked up his boyfriend’s contact information in the hospital system. When I got in touch with him, he told me that he’d just attended his partner’s funeral. There, standing in front of the tombstone, he’d received a message notifying him that his green card application had been accepted. He’d told no one, not even their closest friends, that his boyfriend had died from AIDS. Who else was there for him to talk to? This event confirmed to me just how important and effective my interactions with patients could be.

Sometimes, even just the sight of our plain white gowns can be a source of comfort. Once, when I was working a night shift in 2015, a patient of mine suddenly hugged me. Crying, he’d just had a nightmare. Nightmares are a common side effect of the antiretroviral drugs he was taking, and when he woke in a panic, he’d seen my white gown and clung to it as he tried to calm down.

That same year, we admitted an infant who was born HIV-positive. A regular patient for years, the boy has since learned to be at ease around anyone in a white gown. Once, when I ran into him in the hospital building, he greeted me like an old friend and asked me to play with him. Incidents like these have caused me to rethink the significance of our otherwise drab, loose-fitting uniforms. To us, they might be poor-quality stain magnets, but to our patients, they represent peace and a sense of safety.

In recent years the government has taken steps to raise public awareness of HIV/AIDS and encourage members of high-risk groups to get tested, and our hospital now admits between 1,200 and 1,400 such patients every year. Many of them are members of the men who have sex with men community — a fact that contributes to the disease’s stigmatization among the broader Chinese public.

In one recent instance, upon finding out that her husband had been diagnosed with AIDS, a woman threatened to commit suicide. She said she could accept any diagnosis but AIDS, which she saw as a “dirty,” shameful, and fatal disease.

I tried to reassure her by telling her that the hospital has strict confidentiality mechanisms in place to guarantee patient privacy. We never release a patient’s medical information without their prior authorization, and in our interactions with patients, we are careful never to ask them how they acquired the disease. Comforted, the woman finally began to calm down.

Some view working closely with HIV-positive patients as risky, but while I’ve personally been exposed to the virus on two occasions, such instances are more bothersome than life-threatening. We’re required to start a 28-day course of medication within 24 hours of any potential exposure, followed by screenings at the one-month, three-month, and six-month marks. The first time I took the drugs, I felt some mild stomach discomfort, but by the second time, the drugs had improved, and I experienced no side effects.

In 2017, I took a nursing course at Fudan University in Shanghai. While there, I was pleased with the number of young students I met who expressed an interest in one day working in with HIV carriers and AIDS patients, a sign that the next generation may be more open-minded than the current one. Ultimately, while HIV is virus, its channels of transmission are very limited, and even if infection does occur, you can still lead a very long life with the proper medication. As long as you wear a condom, get tested if you’ve engaged in high-risk behavior, and get treated in a timely fashion, HIV and AIDS are nothing to be afraid of.

As told to Sixth Tone’s Ni Dandan.

Editor: Kilian O’Donnell, portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: Wang Lin performs her nursing duties in Shanghai, Feb. 2, 2019. Courtesy of the author)