A State Scientist’s Views on China’s Microchip Industry

They’re tiny, yet powerful — and may be worth billions to Chinese scientists. Microchips, the tiny pieces of computing found in everything from cellphones to satellites, make up a growing industry in China — one that exceeded $100 billion in 2017 and 2018. Overall, the country is also the largest consumer of semiconductor products, occupying an estimated 60 percent of the global market, according to the professional services company PricewaterhouseCoopers.

But if the Chinese microchip industry is to realize its potential, it’ll have to bounce back from a turbulent 2018. In April, the U.S. government banned American companies from selling parts and software to Chinese telecommunications giant ZTE Corporation, claiming that ZTE had violated sanctions on Iran and North Korea. ZTE briefly ceased operations, before paying a fine of $1.4 billion to have the ban lifted.

However, the recriminations didn’t stop there: In August, the U.S., citing national security concerns, applied restrictions to 44 Chinese businesses and other entities, many of which work in defense, satellite communications, and aerospace industries. In October, the U.S. stopped exporting to a Chinese government-sponsored microchip producer in southern Fujian province. And the new year has brought little respite: American investigations into Chinese telecommunication giant Huawei brought a litany of criminal charges against the company and a formal extradition request for its Canada-based chief financial officer Meng Wanzhou, whom the U.S. suspects of breaching sanctions on Iran. The developments have ratcheted up tensions between the world’s two largest economies, with the Chinese government describing Meng’s detention as “immoral.”

The standoff has sent ripples through China’s still-developing microchip industry. Domestic output increased from 65 billion chips in 2010 to more than 150 billion in 2018; in August last year, China’s chips were worth an estimated 830 billion yuan ($123 billion), accounting for more than a quarter of estimated global market sales. But Chinese design and manufacturing technology still lags significantly behind the U.S. — the world’s foremost microchip producer. The gap persists despite heavy government investment dating back as far as the 1980s. In 2017, nearly 90 percent of the chips used in China were either imported or manufactured in China by foreign-owned companies, according to The Wall Street Journal.

The past year has brought change to the work of Zhao Yuanfu, vice director of the Science and Technology Committee at the Ninth Academy of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC). The state-owned corporation designs and manufactures a type of chip technology that already rivals that of the U.S., Zhao says: space-grade microchips, those used mainly on rockets, spacecraft, and satellites. Zhao’s team’s chips feature heavily in China’s space program, and Zhao himself won the 2018 State Technological Invention Award for his work. Space-grade chips must be “radiation-hardened” — that is, able to withstand the higher levels of ionizing radiation that occur in space and can cause satellite systems to malfunction.

Although CASC has developed space-grade chips since the 1990s, this field, too, was once dominated by U.S. technology. Now, after more than a decade of work and billions of yuan in state investment, China’s space-grade chips are almost entirely domestically produced, Zhao says. His team has developed more than 300 different kinds of components. China’s flagship geolocation satellites — the BeiDou Navigation Satellite System — uses over 1,000 chips on each satellite developed by Zhao’s team.

Zhao is a state scientist whose work, particularly when deployed in navigation satellites, serves to advance China’s national interests. Some of his opinions on how the country could realize those interests — for example, by acquiring shares in foreign technology companies — may sound controversial to Westerners. Sixth Tone sat down with Zhao to hear his views on China’s microchip development and the repercussions of the country’s trade tensions with the U.S. on the chip industry. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: How has China’s microchip industry changed since you started out in the 1990s, and what effects did the events of 2018 have on the industry?

Zhao Yuanfu: At the start of “reform and opening-up” in 1978, there was a huge gap between domestic and overseas microchips. At the time, Chinese chips lagged almost 10 generations behind developed countries. Even today, domestic microchip production is still messy. Last year, when the U.S. banned its companies from selling to ZTE, the effect on our production of critical microchip-based hardware — like phones and computers — was devastating.

I think China’s chip industry is still playing catch-up because of the culture of imitation that runs through the industry here. Ripping off other products — clothes, for example — is a good way to catch up with your competitors. But because a new generation of microchips develops very quickly — around every 18 months — imitating existing chips ensures a gap [between Chinese products and foreign chips]. When you start copying a new product, your competitors are already producing the next generation. There’s no way that China will catch up with the rest of the world by doing that.

In recent years, private Chinese companies like Haier, Hisense, and Gree Electric have diversified their businesses into microchip research. They are all realizing that if their overseas chip suppliers cut exports, their companies will die within months. They wouldn’t stand a chance.

Sixth Tone: How can China maintain high-quality space-grade microchips when faced with import bans from foreign countries?

Zhao: The U.S. has restricted microchip exports to China in two main ways. The first is a ban on microchips that have particular space and military uses. The second is a ban on microchips above certain capabilities, for which Chinese importers need a permit from the U.S. Department of Commerce. The permits require that such chips are used only for designated purposes, and this sometimes leads to chip smuggling [between the U.S. and China], arrests, and imprisonment.

In fact, export restrictions on space-grade chips to China have been going on for decades. This has actually benefitted China in unexpected ways over the years, because we’ve had to develop our own. For example, the government established the [CASC-operated] Beijing Microelectronics Technology Institute in 1994. I joined in 1996 as an expert in radiation hardening — the technology that makes microchips resistant to space radiation. At first, we tried to copy the ways that the Americans process their chips in order to harden them. But at that point, our processing capacity was at least five generations behind the U.S., so we couldn’t match them.

So we went back to the drawing board and created a chip whose very design — not just its later processing — makes it resistant to radiation. From 2003, we established a project for producing radiation-hardened central processing units (CPUs) for satellites — the “brains” of satellites that receive, process, and interpret messages. We spent four years learning the basics, and another three years designing and manufacturing the CPU.

Meanwhile, thanks to the 909 Project — a 4-billion-yuan government-backed project launched in 1996 that aims to manufacture high-quality microchips at a large scale — we were able to produce space-grade microchips that have gradually caught up with American technology. I’d say these chips are now at a world-leading level, although that’s partly because space-grade microchips tend to be simpler to design and manufacture than civil-use chips.

So the current U.S. restrictions may be hard for China in the short term, especially for private businesses. But my experience at CASC makes me believe that in the long term, it could eventually be a benefit, as it will force us to innovate our way out of trouble.

Sixth Tone: What were the first satellites to use your microchips?

Zhao: In the early 2000s, no one dared use domestically produced components like ours — we were making these space-grade circuits, but no one would use them! So in 2003, when CASC’s Fifth Academy — a different branch from us that makes satellites and manned spaceships — came to negotiate a price with us for using our chip in one of their satellites, I said they could pay whatever they wanted, as long as they used it. Fortunately, they accepted and the circuit worked well in space.

Two years later, we were asked to manufacture backup circuits for one of the early BeiDou geolocation satellites. In 2008, one of their core chips malfunctioned during launch and had to fall back on our backups. They worked really well. I think that was the point when domestic clients realized that CASC’s microchips could compete internationally. Today, a BeiDou satellite uses more than 1,000 of our chips in its main operating system. We also supply chips to China’s space station Tiangong-2, and export them to Russia, Germany, France, and other countries.

Sixth Tone: What do you think China needs to do to catch up with developed countries in the chip industry?

We should make up the gap in areas we fall short and strengthen what China is already good at. Developing essential capabilities — like strong supply lines — always takes time, but we have to do it. And if we can’t develop key technology ourselves, we should buy shares in overseas companies who can.

In a globalized economy, you can’t rely solely on yourself. But you must hone your strengths, as they earn you a spot at the bargaining table. HiSilicon, a subcompany of Huawei that focuses on microchip development, is now the biggest microchip-design company in China. Huawei is increasing the number of high-end phones that run on HiSilicon’s chips, and at least 60 percent of codec chips in the world’s surveillance cameras come from them. If they continue research and development, they will define the future of the microchip industry.

In the past, we always bought into the “Taiwan model,” which outsources the process of chip production — design, manufacture, packing, testing — to different companies. Yet none of the world’s biggest companies did it that way; they all made their own products completely in-house. We may not think of IBM as a microchip company, but they actually have the best microchips in the world. Sony is famous for its cameras, but it’s only because of its amazing image-processing chips that it has that reputation.

In China, no matter what business you’re in, you have to be able to compete. If you have a product — an air-conditioner, for example — and want to become the market leader, your chips are what add the most value.

I’m not arguing for China to retreat into itself and try to produce everything domestically — that leads to blind nationalism. Key to where our chip industry goes next will be how we define our aims and embrace a spirit of cooperation.

Editor: Matthew Walsh.

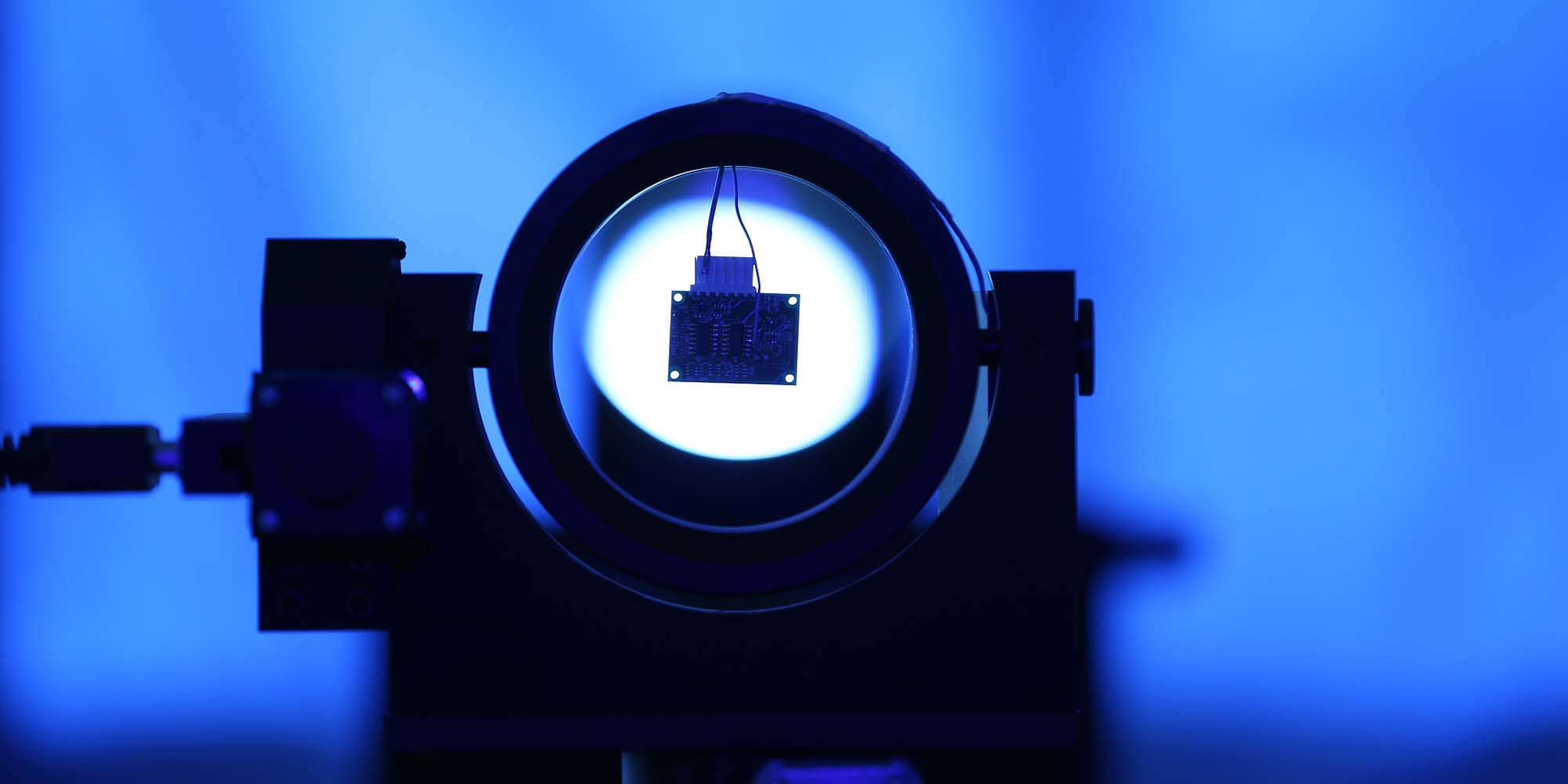

(Header image: A chip used in satellites is tested at a laboratory at Northwestern Polytechnical University in Xi’an, Shaanxi province, December 2015. Gou Binchen/VCG)