Where Watchful Eyes Are Welcome

CAIRO — Seven months into her livestreaming career, Nada Khaled Mohamed, 20, still gets nervous every time she goes on air. But after taking a few minutes to compose herself, she turns on the camera and warmly greets her audience, her hands tucked into the shape of a heart: “Welcome! I want an island! I want a Ferrari!”

It’s a sweltering summer afternoon, but Mohamed seems not to notice the heat as she chitchats with her viewers in excited Arabic. She responds to their comments, many of which compliment her looks — “You look so beautiful!” — and she talks about her day. She’ll often sing them a song.

The exchange is at most mildly flirtatious, but in a socially conservative region, such unscripted interaction seems plenty exciting for Mohamed’s mostly male followers. They tip her generously with virtual gifts — such as “islands” and “Ferraris” — that can be converted into real money on 7Nujoom, one of the first Chinese livestreaming apps to enter the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, in 2014.

Plenty of other Chinese companies have since followed, joining an overall push to explore foreign markets under the banner of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, of which Egypt is a key participant. The region’s 450 million people — roughly one-third of whom use smartphones — have proven enthusiastic streamers. Last year, MENA users spent $81.4 million on current livestreaming market-leader Bigo Live, according to Sensor Tower, a company that tracks app data. Despite only having 13% of its total global users, the region supplies nearly half of the app’s revenue.

Mohamed streams for hours on end, interrupted only when mosques throughout Cairo sound one of their five daily calls for prayer. She has quit her part-time job clearing goods at a logistics company that paid at best $80 per month, required a two-hour commute to get there, and had her working in the scorching sun. Now, she can make up to $850 — about triple her father’s monthly income — from the comfort of her family’s 10th-floor apartment. At first, it seemed too good to be true, she says: “Hearing about the livestreaming app, I felt rather confused: It’s impossible for someone to make money by just talking in front of the camera.”

During her first livestream sessions, Mohamed felt embarrassed to talk with men: “I won’t talk to strangers on the street, let alone have personal conversations with a man.” Initially, Mohamed’s mother was wary of her daughter running into miscreants. “I was listening outside during the first month when my daughter started broadcasting her livestreams,” she says. But the family — with three daughters and one son — faces the prospect of three dowries and wants to put the boy through college, and so could use the extra income. Moreover, Mohamed’s mother is among the just one-quarter of Egyptian women who are formally employed, and she knows the value of earning your own income. She encouraged Mohamed to keep at it.

At home, Chinese tech companies employ small armies of moderators to remove content from their apps for one reason or another. This operating model proved adaptable to the conservative sensitivities of the Middle East and North Africa. 7Nujoom filters out any religious, political, or lewd content — to the relief of mothers like Mohamed’s. She sees the censorship as a barrier between her daughter and the “unspeakable” world. Mohamed says she chose 7Nujoom over more international platforms, in part because it had less “indecent” content. Together, Mohamed and her mother also managed to convince her father, who was kept in the dark at first.

“(Content regulation) is a core competitive strength that allows us to have a foothold in the Middle East market,” says Liu Boxia, COO of Fission, the company behind 7Nujoom, sitting in his Beijing office during a July interview. Catching forbidden content depends on public tipoffs, a database of sensitive words, and around-the-clock monitoring by employees. To that end, the company set up regulatory departments in Beijing, Cairo, and Morocco’s Rabat. Sensitive words are automatically masked and flagged. “Then, our regulators will impose the corresponding punishments on these users, such as blocking posts for a short period, kicking them out of the studio, and banning the account,” Liu says. This way, content on 7Nujoom is kept “healthy,” though some users complain that vague definitions of what is allowed have made the app’s content less rich than that of its competitors.

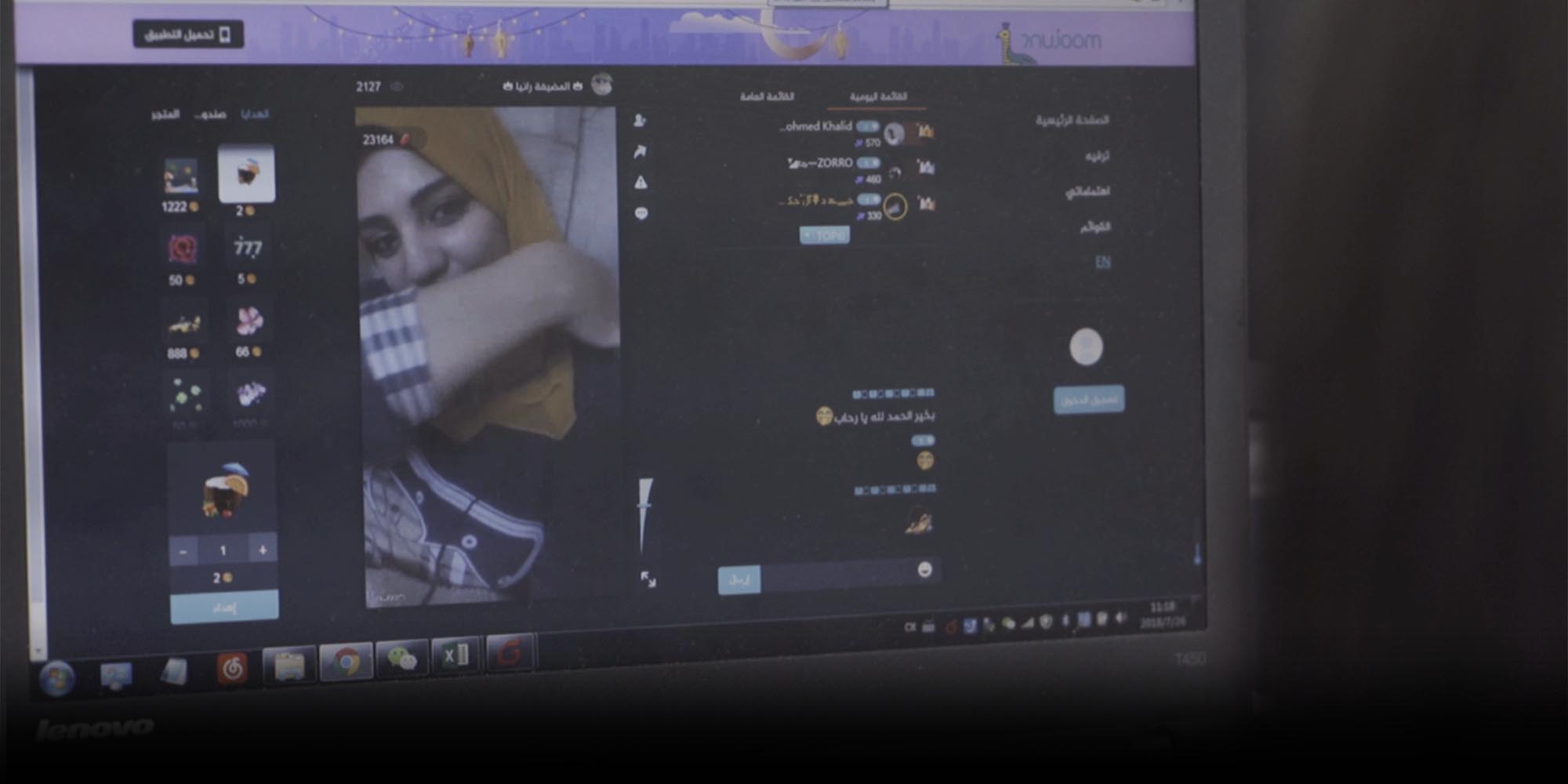

At around 9 in the evening, local time, 7Nujoom sees its peak in daily users. Amr, a member of the nighttime regulation team in 7Nujoom’s Cairo office, sits behind a desk with two computer screens, on which he monitors dozens of streamers in real-time. If a user reports an infraction, he jumps in instantly. His team punishes about 200 viewers and 10 streamers each night, he explains. There are regulations for streamers, that, for example, stipulate they are not allowed to lie down or show too much skin.

Regulation team leaders regularly go to Beijing for training on how to keep the balance between entertainment and civility. There is more at stake than just the disapproval of concerned parents. Last July, Egypt’s parliament passed a media supervision law that stipulates that any social media account with more than 5,000 followers is subject to the same scrutiny as regular media, meaning popular streamers can be held legally accountable if they spread “false news” or insult religion.

Much of Mohamed’s income comes from wealthy viewers from oil-rich countries across the Red Sea. When a user from Saudi Arabia joins the session, she stops talking in the local dialect and switches to humming a well-known Saudi ballad. The Chinese livestreaming business model — funded not by ads but by virtual gifts — depends in large part on such wealth gaps, says Liu. Streamers are rewarded with virtual gifts that are purposely designed to appeal to rich viewers’ desire to show off, such as with digital “Ferraris.”

Egypt, where most of 7Nujoom’s streamers are from, has a per capita GDP of just $2,400, whereas Saudi Arabia, the main source of the app’s paying users, has a per capita GDP of nearly $21,000. Liu says the best-spending users work in the gold or oil industries. Some spend thousands of dollars per night. “We regard clients with a single recharge of more than $5,000 as our super-VIPs,” says Han Jiatong, an Egypt-based 7Nujoom employee responsible for user service. Some of these super-VIPs ask for their profiles to look like they are Middle Eastern royalty. “When VIPs make such requirements, we will immediately contact the Beijing head office and have colleagues at the design department help these customers create a special profile page,” she says.

In northern Africa, Chinese livestreaming apps often cooperate with local agents to find streamers for their platforms. Khaled Osman, 50, operates an entertainment company in Cairo. Since 2014, he has worked for his Chinese partners to find livestreaming talents. He usually goes to the opera house, where there are “many young people with musical talents,” or to university campuses to spot beautiful faces. Plenty of the people he approaches are initially skeptical, as Mohamed once was, that there really is that much money to be made. But with high youth unemployment, streaming can prove a welcome source of income.

After watching several livestreaming sessions, our interpreter Ahmed, a young man with a doctorate in religious studies, says it reminds him of belly dancing. A symbol of Arab culture, many countries in the region nevertheless forbid women to belly dance in public. In decades past, men from the relatively religiously stricter countries in the Gulf region would travel to Cairo to admire its dancers. But as with belly dancing, livestreaming is sometimes accused of immorality by critics in the region. In 2016, a Moroccan YouTuber criticized 7Nujoom for allowing users to exchange indecent photos. As the story got play in mainstream media, the company kept its head down, apparently convinced in its strategy of content regulation.

For a while, 7Nujoom seemed promising to investors. Parent company Fission received 20 million yuan ($3.15 million) in angel funding in 2015, and then another 105 million yuan in round A financing in 2017. But as it helped prove the viability of the MENA market, bigger players stepped in — mirroring what had happened years earlier in China itself. At the end of 2016, Bigo Live, which is linked to Nasdaq-listed Chinese livestreaming giant YY, launched on Middle Eastern app stores. It has grown to become the top platform in the region.

“The competition is so fierce that various Chinese livestreaming companies are stealing talents from their competitors,” says Yang Yue, an agent who represents streamers in Egypt. He says there are at least 25 apps with Chinese backgrounds that focus on livestreaming and short videos on the MENA market. Bigger companies have deeper pockets to attract talented streamers. And there is now a larger variety of formats, from voice-only livestreaming for people who don’t want to show their faces, to one-on-one video chatting for the intimately inclined.

Around Christmas 2018, 7Nujoom recalled all its Chinese staff from Egypt, confirming a monthslong rumor that its Cairo office would close down. “At first, the head office just claimed that there was something wrong with the remittances,” a former Egypt-based employee says in February. “But beyond my expectation, the headquarters were almost empty, and there were only four employees when I returned to Beijing.” In February 2019, 7Nujoom was removed from both the iOS and Google Play app stores. By then, Liu, the COO, had already left his post. Liang Yaolong, former manager of the app’s Egypt office, says that many members of the team behind 7Nujoom are now developing a social app aimed at the Indian market, a new frontier.

For three months leading up 7Nujoom’s closure, Mohamed hadn’t received any of the money she had made. Still, the app’s demise saddened her, as it meant losing online friends from around the world. “Even men over the age of 60 would share their experiences with me,” she says. She also invited her real-life friends to watch her livestreams. Gradually, her entire social life was centered around livestreaming.

Mohamed tried a competitor, Prince, which launched in November and offered a $300 monthly base salary. But she left quickly, because she didn’t like its payment rules. There’s no lack of alternatives, however. Earlier this year, the Chinese livestreaming app Yome Live launched in the Middle East, and in 2018, China’s ByteDance-funded TikTok was the most-downloaded short video app in the MENA region.

In any case, Mohamed, now a junior in university majoring in business, plans to continue streaming for some time. Her mother is supportive, but after 7Nujoom shut down, expressed a desire for her daughter to start thinking about a more traditional career, perhaps in banking, or even following her mother’s footsteps and starting her own business. It’ll be hard to earn as much as she does livestreaming. “I’ll give up being a streamer if my future boyfriend doesn’t want me to,” Mohamed says. But she hopes he’ll understand.

Contributions: Ahmed Medhat, Ye Luting, and Liu Jingwen; editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: A 7Nujoom worker monitors MENA-region livestreamers in Beijing, July 2018. Wu Yue/Sixth Tone)