The Chinese Students Stuck in Fake Majors

JIANGSU, East China — Zhao Yangyang thought she was on the fast track to a bright future. She was three years into a program to become a high-speed rail attendant — a secure job that would allow the then-18-year-old to travel across the country. But last August, those plans suddenly derailed.

Zhao knew something was wrong when she arrived to pay the tuition fees for her final year at Mingda Polytechnic Institute, a private vocational school on the outskirts of her hometown Sheyang, in eastern China’s Jiangsu province. Instead of allowing her to register like usual, the receptionists told Zhao that the school wanted her to transfer her program from high-speed rail attendant to tourism management.

Zhao was confused. She had no interest in tourism. In a few weeks, she was supposed to be starting an internship as an attendant. Her new uniform was already hanging in her closet. She asked why the school wanted her to switch programs on such short notice.

That’s when Zhao received the bizarre, yet life-altering news. “They said that the (high-speed rail attendant) program did not exist, and that she would have to transfer to the tourism program,” Yang Ling, Zhao’s mother, tells Sixth Tone.

All around her, Zhao’s classmates were having similar exchanges with Mingda staff, and things began to get heated. Eventually, the school agreed to set up a meeting between the students and the school’s executives.

The meeting took place three days later. The families of nearly all 35 students in the high-speed rail attendant program squeezed into a conference room on the Mingda campus. The school’s vice dean, Zhou Kaimeng, said a few words, announcing that the school did not have a government license for the program, and so it was impossible for the students to graduate. He urged the students to transfer to tourism management. Zhao burst into tears.

“I’d spent years working on this, and now someone was telling me that it was all for nothing,” she says.

Many other students across China have been caught up in fake major scandals as the country’s private vocational schools struggle to recruit new pupils. In May, students at a vocational school in the eastern city of Nanjing disputed with staff after they discovered they would not receive qualifications for nursing, as they had been promised, but in home economics.

According to Zhang Run, a lecturer at the People’s Public Security University of China, there are many similar cases that go unreported because the students’ families reach a settlement with the school.

Zhao’s family had even heard media reports about a similar scandal at Mingda in 2016; but when confronted, the school assured them that the same thing would never happen to them. “The teachers looked gentle and well-mannered — some are even Ph.D. advisers,” says Zhao Yongjian, Zhao’s uncle, who works as a truck driver. “I couldn’t imagine them doing such a thing.”

Private Dreams

The fake major phenomenon comes as deeper challenges plague China’s private vocational education system. With vocational schools training 70% of new workers entering the manufacturing sector and emerging industries, it’s a sector the government considers integral to the country’s economic future.

The State Council, China’s Cabinet, has been calling for the market to play a bigger role in the vocational education system since 2013. But this commitment to market-driven education has not been able to prevent many private vocational schools from falling into financial distress.

Public colleges receive the lion’s share of government funding and policy support, meaning that private schools rely heavily on income from tuition fees. And, for many schools, this income is on the decline.

“Enrollment at (private) vocational schools in China is falling — you could even call it a crisis,” says Xiong Bingqi, an education policy expert at 21st Century Education Research Institute, a Beijing-based think tank.

China’s school-age population has been decreasing since 2007, according to Ministry of Education data, putting pressure on the higher education system as a whole — private vocational schools most of all.

Vocational higher education institutes struggle to compete with universities, as many Chinese parents still believe an academic degree will provide their children with better career options. Private vocational schools, meanwhile, often lose students to better-funded public colleges with superior facilities and teaching staff.

“Private vocational schools are at the bottom of the entire enrollment system,” says Liu Yunbo, a lecturer in the Institute of Vocational and Adult Education at Beijing Normal University.

These pressures drive many private schools to use any means necessary to attract students — from offering junior high school graduates free gadgets to sign up for a program, to offering majors of dubious legality.

“If the schools can’t recruit students, they have to close,” says Guan Hua, a law professor at Northwest University of Political Science and Law in the city of Xi’an. “They hang up lamb in the window, but sell dog meat.”

False Promises

Zhao knew none of this when she started thinking about her future in 2015. She was 15 years old and about to graduate from junior high school. Sheyang’s education bureau had arranged for local vocational colleges to talk with the students about their career options. One of those schools was Mingda.

Shen Xiaoqin, the mother of one of Zhao’s classmates, remembers representatives from Mingda promoting the new high-speed rail attendant program heavily at the event. China had been increasing investment in bullet trains, and a new line running through Sheyang was due to open in late 2018. It sounded like perfect timing.

“They promised us that there would be guaranteed jobs and that students would get assigned to workplaces with a good salary,” says Shen.

Shen was so impressed that she persuaded her son, Wulong, to sign up for the program. The clincher for Wulong was that, as his mother had agreed to pre-pay 1,000 yuan ($160) of his fees, Mingda gave the 15-year-old a free TCL smartphone — the first mobile phone he’d ever owned.

Zhao Yongjian, Zhao Yangyang’s uncle, also remembers feeling that the high-speed rail attendant program was a smart choice. “I thought this was a booming industry that needed talent, and it should be easy for her (Zhao Yangyang) to secure a job after graduation,” he says.

What the families did not realize was that Mingda had decided to go ahead and offer the major without first obtaining government permission. “It is illegal to enroll students in a program that has not been approved (by the local education bureau),” says Guan. “This constitutes civil liability, though not necessarily criminal responsibility.”

But Mingda was desperate to recruit new students by this point. The school’s quota allows it to recruit up to 1,650 students per year, but since 2013, it has never managed to attract more than 700 in a year, according to Mingda’s annual reports.

By 2015, Mingda’s finances had deteriorated so badly, it was unable to pay its teachers on time, Liu Bubai, an official in Sheyang’s education bureau, tells Sixth Tone. The school requested enrollment assistance from the local government.

Mingda had a history of irregular marketing activities, such as offering rewards to entice students to sign up for tuition, much like the smartphone offered to Wulong. But officials finally agreed to include Mingda in a government-supported enrollment program — usually a privilege only granted to public colleges — as they figured the school’s failure would damage the local economy.

The education bureau ordered Mingda to hand over all promotional materials for inspection. It also checked the students’ application results reported by the junior high schools. But the officials did not notice anything suspicious.

“We only found out about the (fake major) situation when the students were getting close to graduating,” says Liu. “We didn’t know that they (Mingda) were still recruiting students, even though the program was unapproved.”

Next Steps

The Chinese government has been trying to crack down on schools luring students into illegal programs. In 2016, the country amended a law to distinguish for-profit and nonprofit institutions — a move designed to increase supervision of for-profit schools like Mingda.

Recent policy announcements are expected to help alleviate underfunding in vocational education. In April, the State Council adopted a plan to raise enrollment at vocational schools by 1 million students and increase funding by 100 billion yuan.

But for the families already caught up in a fake major scandal, there are no good options — only less-bad ones. Such was the case at last year’s meeting between Mingda and the high-speed rail attendant students.

Of the 35 students enrolled in the program, 30 eventually accepted Mingda’s offer to transfer to a tourism major, even though it meant extending their studies by a year, receiving only a partial refund on their tuition fees, and — of course — possibly changing their career plans.

But the other five students, including Zhao Yangyang, decided to take a stand. After talks with Mingda broke down, they took the rare decision to sue their school for false advertising and fraud. Their lawyer filed a lawsuit at the People’s Court of Sheyang in December 2018, and the court has held four hearings on the case so far.

The legal proceeding is a big gamble for the families. By refusing to switch to tourism, the students have accepted that they will need to start their studies again from scratch. Their three years of learning at Mingda cost more than 35,000 yuan in tuition fees — a huge sum for Zhao’s parents, who work at a local factory and repair workshop.

The legal fees have cost another 15,000 yuan, and there is no guarantee the court will award them significant compensation. The verdict is expected to be announced in September, though the court is yet to confirm a date.

Zhao Yongjian says the families are determined to hold Mingda accountable for its alleged crimes. “You cheated our kid, and you didn’t even apologize,” he says. “I feel really upset. I definitely want to confront them in court.”

Several of the plaintiffs express frustration at the lack of consequences for Mingda so far. Though the Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education publicly criticized Mingda last September for malpractice in a post on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform, the provincial government is yet to take concrete actions to punish the school.

In early 2018, Mingda was acquired by the Northern Investment Group, a Beijing-based joint-stock company that runs 18 higher education institutions. When contacted by Sixth Tone, Zhu Li, an official at the school’s admissions office, blamed Mingda’s low student numbers and mismanagement on its previous owners, declining further comment.

And yet, several parents of the affected students tell Sixth Tone, the school continues to promote the high-speed rail attendant program.

Jiangsu Provincial Department of Education did not respond to Sixth Tone’s request for comment by time of publication.

Zhao hopes to start her studies again one day, but she is struggling to move on. The first high-speed train left Sheyang’s new station in January. She was not there to see it. “I’m a waste of space at home,” she says. “I’m almost 20 now. I tried to find a (decent) job, but without a diploma, I couldn’t do anything.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

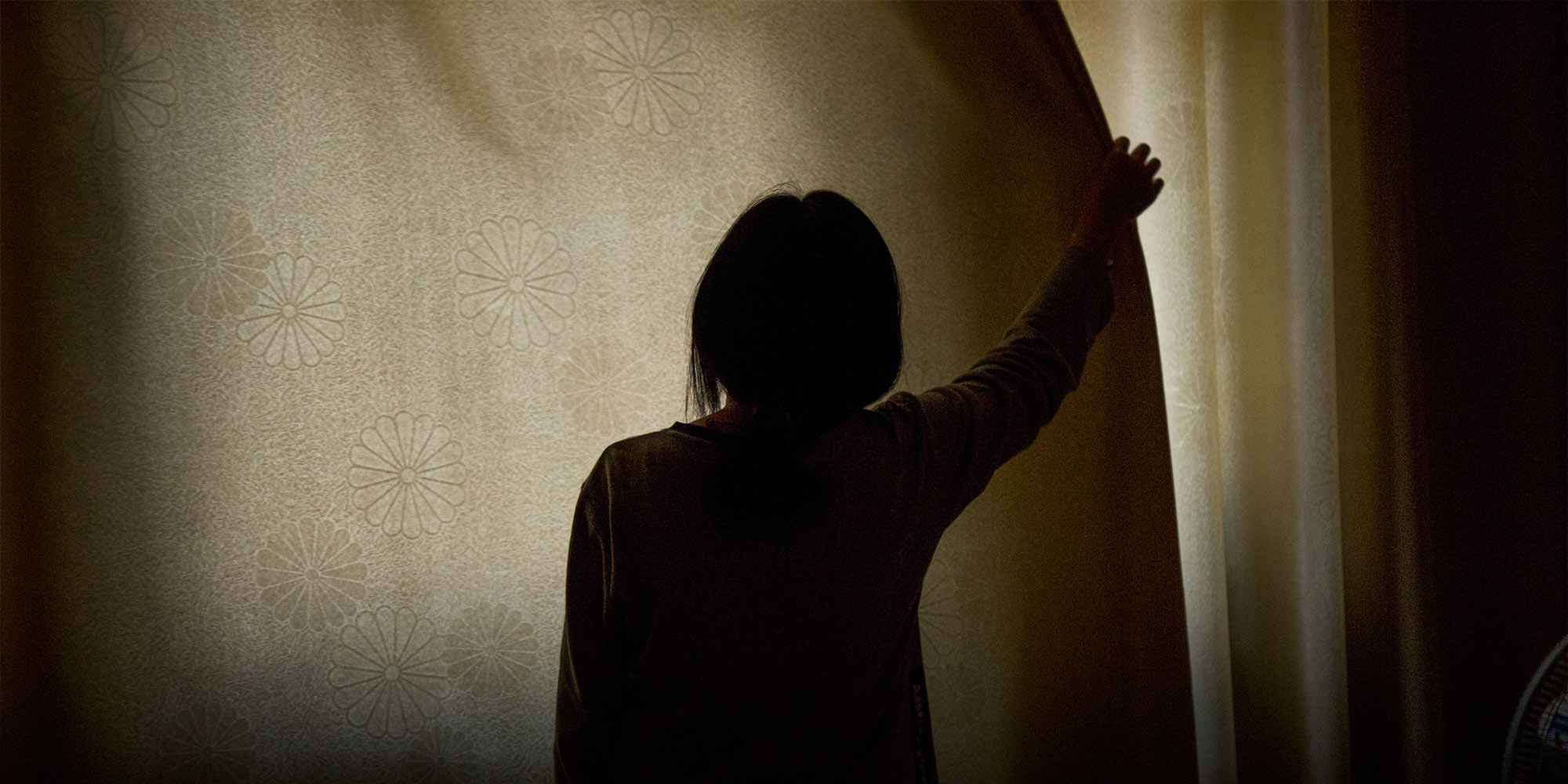

(Header image: Zhao Yangyang pulls the curtain in her bedroom in Sheyang, Jiangsu province, July 30, 2019. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone)