Chinese ‘Deepfake’ App Censured Over Privacy Concerns

A newly released face-swapping app has come under fire for a clause in its terms and conditions allowing it to sell users’ photos and videos, Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, reported Sunday.

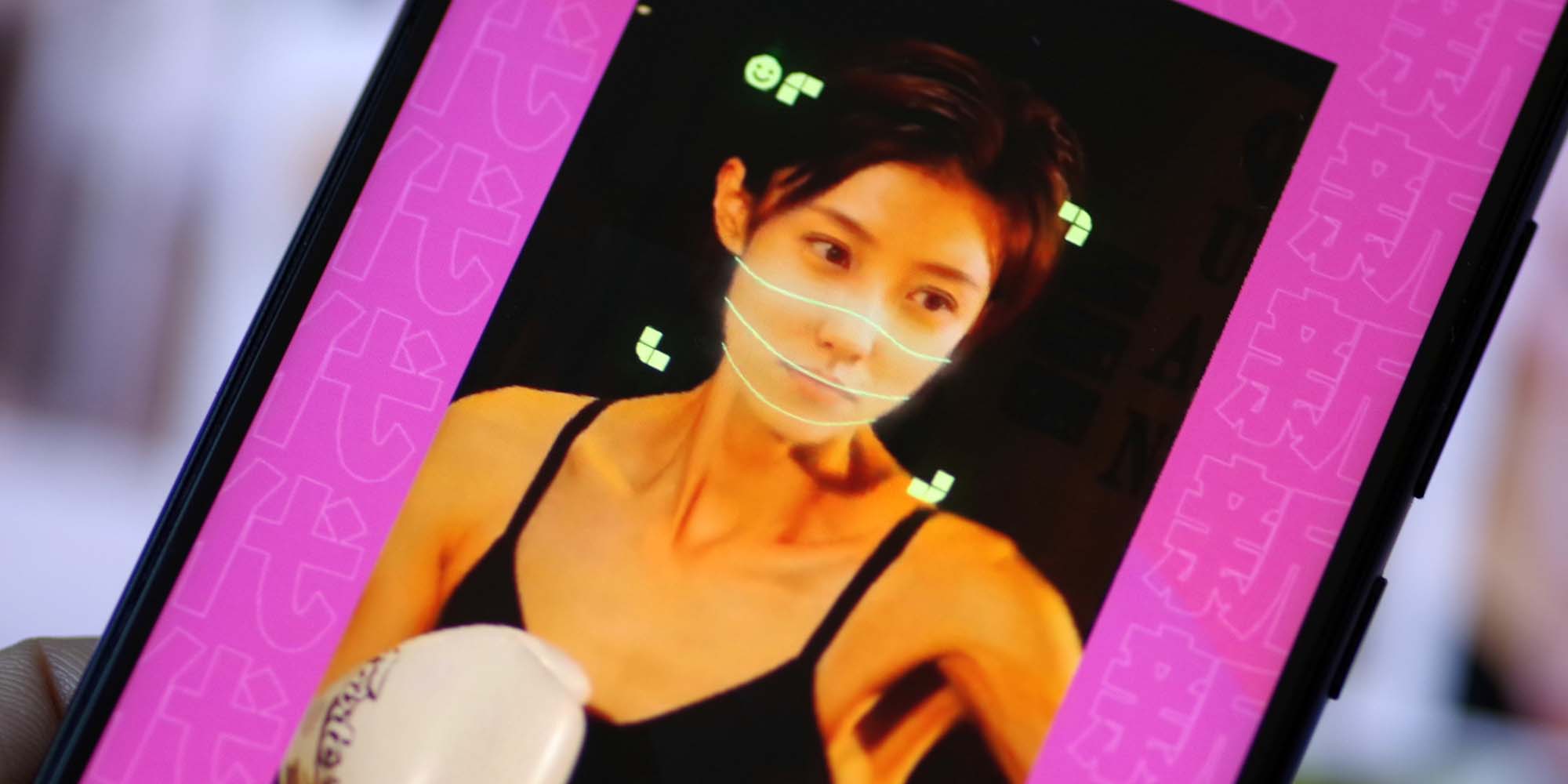

Zao — meaning “make,” “build,” or “fabricate” in Mandarin — turns users into “stars” by digitally grafting their faces onto the bodies of celebrities in scenes from movies, TV shows, and music videos to create what is known as a “deepfake,” a technological portmanteau combining “deep learning” and “fake.”

After downloading the app, users are asked to upload photos of themselves that can be used to make a face-flipped clip of their choice. Each video takes less than 10 seconds to generate, with enhanced quality if users agree to let their cellphone’s camera film their face from various angles, and while blinking their eyes or opening their mouths.

Lei Xiaoliang — head of the Changsha-based company that developed Zao — also co-founded Momo, one of China’s most popular dating apps. Since its release Friday, Zao has rocketed up the charts to become the No. 2 most widely downloaded free app on Apple’s China app store as of Monday evening.

Over the past three days, Zao users have been sharing self-made videos on their social feeds on WeChat, Tencent’s ubiquitous messaging app. Zao’s average ratings, however, dropped dramatically across several app stores after netizens discovered a problematic clause in the user agreement. The clause — which has since been deleted — said Zao maintained the portrait rights to user-supplied images within the app, as well as the right to distribute or sell such images.

On Monday, Sixth Tone found that, while video clips and GIFs could still be downloaded from Zao and shared on WeChat, the messaging app had blocked users from accessing Zao within its interface: Now, when WeChat users click their friends’ posts shared from Zao, they are greeted with a message saying the third-party app “has been reported multiple times and contains security risks.”

Meanwhile, on China’s other dominant social app, microblogging platform Weibo, a hashtag about Zao content being partially blocked on WeChat had been viewed over 160 million times by Monday evening.

On Sunday, Zao addressed the public’s privacy concerns in a Weibo post. “We understand everyone’s concerns about privacy and have received all of your feedback,” the app wrote. “We will make changes in areas we hadn’t considered well, and we need some time (to do this).”

The current version of Zao’s user agreement is prefaced by a note clarifying that “user content will remain exclusively with Zao” unless users consent to having it shared elsewhere. When users delete videos, they are simultaneously removed from Zao’s servers, the agreement further states. The original clause about Zao’s unfettered, permanent ownership of its users’ portrait rights has been removed.

However, these latest assurances seem to have done little to placate netizens, many of whom are still calling for the app’s removal. “Can the app be quickly taken off the app store? Don’t let it stay there continuing to harm society,” one Weibo user commented under Zao’s post.

On Monday, a Chengdu-based lawyer who blogs under the pen name Fashanshu explained that, under Article 41 of China’s cybersecurity law, network operators are forbidden from sharing citizens’ personal information. If Zao intends to transfer users’ portrait rights and related information to third parties, as suggested by the app’s initial user agreement, this “could potentially violate relevant laws,” the lawyer wrote.

A college student who spoke to Sixth Tone said she was initially impressed by Zao’s capabilities but later worried whether the app could be used to damage reputations. “When I first saw my friend share her Zao video, I liked it quite a lot because the clip was from a movie I like and her face fit (into the scene) perfectly,” said Cai Ziying, a third-year student at Shanghai Lixin University of Accounting and Finance. “But I no longer want to give the app a try because I’m afraid it might put my face on an incriminating video and send it to my parents.”

In February, a deepfake video of mainland actor Yang Mi’s face convincingly superimposed onto Hong Kong actor Athena Chu’s body went viral on Weibo, prompting its creator to come forward and explain that he had merely wanted to make people “more aware of how (deepfakes) could be used in the future.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: A promotional photo for the Zao “deepfake” app. IC)