Too Costly, Too Late: Curable Liver Disease Ravages Rural China

HUNAN, Central China — At the foot of a mountain covered in green and surrounded by farmland, Dashuidong Village in Central China’s Hunan province has long been known for longevity endowed by nature. But nowadays, simply staying healthy has become a distant dream for many in the village.

Dashuidong, in Fuqiushan County, has been haunted by the highly contagious hepatitis C virus (HCV) over the past decade. Along with two neighboring towns — Huangheqiao and Tanshanqian — the mountain villages are now notorious as hepatitis C villages, keeping people away.

There are no accurate statistics on villagers infected by the virus because of people’s lack of awareness of early symptoms and unwillingness to report, as well as the frequent outflow of young people seeking urban jobs. Several villagers in Dashuidong said they think 30% to 40% of the 3,000 people there have been infected with HCV. A local disease control official said the actual figure couldn’t be that high, but he said about 2.8% of the 55,000 people in Fuqiudong County have been diagnosed with an HCV infection, nearly triple the national average of 1%.

Since 2010, new patients have been confirmed in Dashuidong every year, indicating a growing infection. The virus often spreads among family members, causing great economic pressure on households in a village that is among the poorest in the province.

HCV is a contagious liver disease commonly spread when the blood from an infected person enters the bloodstream of someone else, mainly through sharing needles or other equipment to inject drugs. It can also be transmitted through sexual contact or from mothers to infants at birth.

The disease often starts with minor symptoms such as fatigue and mild illness but can evolve into cirrhosis and liver cancer. With the most advanced, direct-acting antiviral treatment (DAA), 90% of HCV patients can be cured.

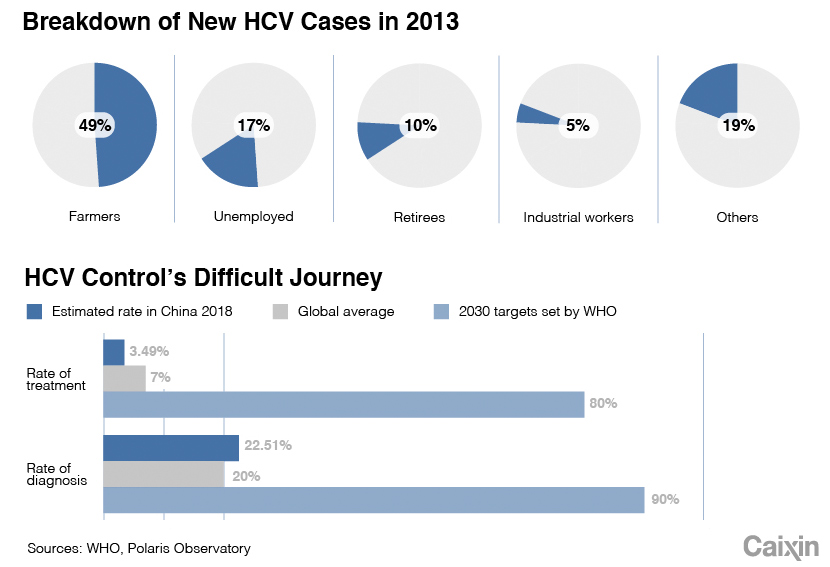

China has the world’s largest HCV-infected population of about 10 million, with 200,000 new virus carriers added every year, according to Zhuang Hui, an academic at the Chinese Academy of Engineering and an expert on HCV prevention.

Most of China’s HCV patients are in less-developed rural areas like Dashuidong Village, where medical services are less advanced and fewer people can afford the latest treatments.

Since 2017, China has approved the domestic sale of a number of drugs for DAA treatments developed by global pharmaceutical giants, but the treatments are largely excluded from the country’s basic medical insurance system, meaning patients mainly have to pay for the medicine themselves. A typical DAA treatment using imported drugs costs between 60,000 yuan and 80,000 yuan ($8,500 and $11,400) for each course of treatment. In 2018, the per capita disposable annual income for rural residents was 14,617 yuan, according to official data.

But a more imminent challenge for China to better control HCV is to effectively find the patients. The United Nations’ World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal in 2016 of eliminating the disease as a global health threat by 2030 by cutting new HCV infections by 90% and deaths by 65%. That would require 90% of HCV infections to be diagnosed in time for effective treatment and 80% of patients to receive proper treatments.

However, only about 22.5% of HCV infections were diagnosed in China in 2018, with 3.49% getting treatment, Zhuang said, citing an estimate by Polaris Observatory, an epidemiology organization that tracks data worldwide on hepatitis C and hepatitis B.

Hepatitis in Dashuidong provides a snapshot of China’s HCV control challenges, reflecting unaffordable treatment, insufficient infection monitoring, and the lack of a proactive disease prevention strategy, analysts said.

The sick village

Several new infections have been found since May, and one victim’s belly swelled up like a balloon as fluid accumulated in their abdomen because of cirrhosis of the liver, one Dashuidong villager said in a phone call.

Many villagers in Dashuidong have lived for years with HCV but have received limited medical treatments. Liu Liangliang, 48, was diagnosed with HCV in 2014, his wife in 2017. To cover their medical expenses, they sold all the pigs they raised for 8,000 yuan. As their bodies weaken, Liu said it will be difficult for them to earn more money to support future medication.

To 75-year-old Zhang Yongshan, who lived on just 3,000 yuan a year from slaughtering pigs with some support from children, the virus in his body seems negligible. He said he will just “let it be.”

No one in the village can say clearly when the virus appeared, but it apparently started to show up sparsely in the late 1990s. Since 2014, more than 10 new infections have been added every year, said Wu Zhifei, a village doctor. According to Wu, about 60 of the patients he treated since 2011 were tested positive for HCV. Statistics from the WHO show that between 70% and 90% of HCV-positive patients are truly infected.

No official data on Dashuidong’s HCV infections is available. In 2017, free health checks in Dashuidong by 360haoyao.com — an online health care service provider — diagnosed 100 infections, people familiar with the matter said.

But it is far from a complete picture of Dashuidong’s HCV infections, as a majority of the village’s labor force has traveled frequently for jobs, like any other village in rural China.

According to a recent study by the local government, a 2015 inspection of the rise in Dashuidong’s HCV infections found no clue to the source of the virus. “There was no reasonable explanation found about what caused (the spreading disease),” a local disease control official said.

Chen Xi, deputy director of the Hunan provincial Disease Control and Prevention center, said the monitoring of HCV infection mainly relies on health care institutions’ reports and inspections of specific groups with higher infection risks, such as drug addicts. But in practice, the monitoring system is not efficient, especially in rural and remote areas, Chen said.

Local authorities have often kept inspections of the disease low profile out of concern that it would cause panic.

Experts interviewed by Caixin said the spread of HCV in China is mainly attributable to the unsafe use of injection equipment, especially around the 1990s. Villagers in Dashuidong recall a late doctor who worked in the village more than 10 years ago and used one needle to treat several people. But since 2013, health care authorities have tightened scrutiny of medical safety and banned repeated use of needles.

Because of the difficulty of tracking the source of the virus, local officials can only fight HCV by enhancing public health care education and by regulating medical practices, a local disease control official said.

Dying to survive

Getting treatment has become a huge burden for most Dashuidong patients. Zhou Yuexi, in his late 50s, was diagnosed with HCV in 2014. Two years later, his wife was also confirmed with the infection. Since then, the couple has traveled frequently between their home and the southern city of Guangzhou for treatment.

“An injection per week for 1,280 yuan,” Zhou calculated. With transportation costs and examination fees, the couple has spent more than 140,000 yuan, thanks to support from their daughter.

Most people who accepted treatments chose the traditional PEGylated interferon plus ribavirin (PR) treatment, which has a cure rate of 50% to 70%. Costs of the treatments range between 20,000 yuan and 140,000 yuan depending on the variety of drug. Usually, cheaper drugs have stronger side effects.

Since 2017, China has approved 11 types of drugs for the more-advanced DAA treatments, which have higher cure rates and fewer side effects. But rural hospitals have little knowledge of the new treatments, and most rural residents can’t afford them.

There are many people who can’t afford even the PR treatments. In Dayudong, Wang Jianrui’s mother, wife, and two sons have all been infected with HCV. The only medicines they take are expired Ribavirin antiviral drugs and some herbal medicines. Wang, who has a disability and can only do limited work, said he worries that the medication will become increasingly unaffordable for his family.

Some people have turned to cheaper generic drugs produced in countries such as India and Bangladesh, purchased through online platforms or other intermediaries. But buying drugs abroad remains in a legal gray zone in China and exposes patients to risks because of the absence of quality control, a health care official said.

The issue was drawn into the spotlight last year by the blockbuster film “Dying to Survive,” the story of a man who smuggles generic cancer drugs into the country for patients who can’t afford brand-name treatments.

The Fuqiushan county government said it has allocated 150,000 yuan of subsidies over two years to support HCV patients. But villagers said the sum is far from enough, as it works out to just 100 yuan to 200 yuan for each person.

Expanding medical insurance coverage may be the most effective way to help patients. But in practice, local authorities and public hospitals have been hesitant to adopt the new DAA treatments over concerns about the impact of rising costs on already strained government budgets.

Meanwhile, requirements linked to better insurance coverage have stopped many villagers from taking the insurance. For example, patients can get larger reimbursements only when they are hospitalized. But many farmers are unwilling to stay in a hospital, as it will interrupt their work and may generate additional costs.

Several cities and provinces including Tianjin, Chengdu, and Zhejiang have launched reforms to include some DAA medicines under local insurance programs to allow partial refunds for patients.

But even in those pilot regions, the new treatments are still costly, as strict requirements are set for reimbursement, the Chinese Academy of Engineering’s Zhuang said. In the rest of the country, the DAA drugs have yet to be covered by the insurance system.

The advance of medical technology is enabling HCV patients to be cured faster and with less suffering. But the new treatments should be more accessible to patients, experts say. Authorities can negotiate with pharmaceutical companies on prices to reduce the burden on the insurance system while ensuring profit for companies, a liver disease prevention expert said.

There are contradictions between medical insurance policy and patients’ needs, which can be solved only with support from the state level, a local official in Fuqiushan said.

“It is not only a health care issue, it is also an issue about social stability,” he said.

This is an original article written by Zhao Jinzhao, Di Ning, and Han Wei of Caixin Global and has been republished with permission. The article can be found on Caixin’s website here.

(Header image: A general view of Dashuidong Village and Fuqiu Mountain in Yiyang, Hunan province, April 20, 2019. Zhao Jinzhao/Caixin)