The Foreign Teachers Caught Up in China’s Education Clampdown

SHANGHAI — In June, Jay finally caught a flight back to South Africa after several harrowing months spent in a detention center in East China. Her crime: Teaching English without a permit.

The 28-year-old, who is speaking to Sixth Tone on condition of anonymity, is one of several foreign nationals that have been detained during a government crackdown on teachers working illegally at extra-curricular cram schools.

Private language schools have been routinely circumventing Chinese employment law for years to save time and money when recruiting foreign teachers. In 2017, China’s Administration of Foreign Experts Affairs estimated that of the 400,000 foreign citizens teaching in the country, only one-third had a valid work permit.

But last August, the State Council, China’s Cabinet, released a document ordering officials to tighten supervision on after-school training centers to ensure “the employment of foreigners … abides by the country’s stipulations,” triggering training center inspections across the country. The crackdown has intensified this year, with local governments launching further inspections and warning parents to look into teachers’ qualifications.

Jay was among the first teachers to be affected, and her story is a telling example of how supervision of the education sector has tightened, but the crackdown fails to deter schools and teachers from ignoring the country’s visa policies.

The young South African had been working at King’s International English — an English training center in the eastern city of Rui’an, Zhejiang province — for nearly a year when local officials came to inspect the school last September.

Like several of her colleagues at King’s, Jay did not qualify for a work permit. Though she is a native English speaker, she had neither a Bachelor’s degree nor the two years’ teaching experience or necessary teaching qualifications.

King’s got around this problem by setting up a shell company and naming Jay an executive, then helping her apply for a business visa. Public business registration records show that six of the company’s seven executives were foreign nationals.

When officials uncovered the shell company, they cancelled Jay’s visa and gave her a 3,000 yuan ($423) fine for illegal employment. But that was not the end of her China career. Just weeks later, King’s offered to help Jay return to China, this time on a student visa. She accepted, and by October she was back teaching classes in Rui’an.

Jay understood she was taking a big risk but says she missed her friends and students in China — and her salary. King’s paid her 10,000 to 13,000 yuan per month, triple the amount she made at home. “I absolutely loved my job,” she says. “And I thought if I got caught, then I would just get deported.”

There are signs that other schools are willing to continue flouting the rules. Although the crackdown led to high-profile arrests of recruiters who had placed unqualified teachers in kindergartens in Beijing and Chongqing this year, multiple agencies are openly advertising English teaching jobs for non-native speakers and non-degree holders in China on Dave’s ESL Café, a popular online jobs portal.

The demand for foreign teachers among private language schools remains enormous, as many centers consider having overseas staff essential to their business, an agent surnamed Hu, who declined to give his first name for privacy reasons, tells Sixth Tone.

“Once there are foreign teachers, the school reaches a higher level — and so do their tuition fees,” says Hu, adding that he has helped more than 300 institutions in eastern China recruit foreign staff members.

In a 2016 survey by consulting firm iResearch, 85% of Chinese parents said foreign teachers were “very necessary for the study of English” as they are more creative and interactive than local educators.

But the supply of native English speakers who qualify for a teaching work permit is limited, forcing many schools to hire teachers illegally. For others, having foreign staff is more about optics than education, and they prefer to hire teachers without a work permit to cut costs.

“Some institutions ask for teachers from European countries like Italy, Ukraine, and Russia,” says an agent at Beijing-based recruitment firm Teachplus, who also requests anonymity for privacy reasons. “Their hourly wage is about 100 yuan — even lower than Chinese teachers in Beijing. But the minimum wage for teachers from America is 200 yuan.”

“The institutions’ major consideration is to increase their selling points,” says Hu. “They think the parents have limited English ability and will rarely have direct contact with the teachers.”

The government has further tightened regulations for education companies this year in a bid to get schools to comply. In July, the Ministry of Education required all online language teaching platforms to make their teachers’ qualifications and experience publicly available on their websites.

The number of inspections, meanwhile, has continued to increase. In August, southern Guangdong province began fresh checks on all public and private teaching organizations with foreign staff.

Jay’s second stint at King’s didn’t last long. She was detained in January, three months after returning to China. In May, she was sentenced to four and a half months in criminal detention. The principal and human resources manager at King’s were also detained, court records show, awaiting trial.

In early September, Sixth Tone contacted King’s posing as a parent enquiring about Jay’s deportation. A spokesperson for the school said that all the foreign teachers at the school had valid teaching qualifications. A staff member from the school’s human resources office added that Jay’s case was “not the school’s problem” and King’s was “not affected” by the incident.

The Teachplus agent says the number of clients asking him to supply foreign teachers with legitimate qualifications has nearly doubled since June. “Employing foreigners without the correct work permit can lead to serious legal consequences, like prison sentences,” he says. “The schools are worried about such punishments.”

Nevertheless, the agent adds that he still doubts the crackdown will continue indefinitely.

Eva, an English teacher from Russia working in Shanghai whose name has been changed out of privacy concerns, also questions whether the crackdown will bring lasting change. “There are not enough English-speaking people coming to China to teach, so they (the schools) have to have people working completely illegally,” she says. “I don’t think it can change on the schools’ side; it has to be changed from above.”

Though she is concerned about the crackdown, Eva has no plans to leave her job at an English training center, where she is officially employed as a business consultant. “I understand the risks of not having a proper work permit,” she says. “I just don’t have many other options if I want to stay in China. I’m hoping that it’ll be fine.”

In July, government inspectors visited Eva’s school. That time, she got lucky. “My manager showed them my visa and they (the inspectors) said, ‘OK’,” she says. “Maybe they did not go into details.”

Experts argue that the most effective way to encourage training centers to be more transparent would be to make China’s work permit system more flexible. In some cases, the government’s strict criteria are putting schools and teachers on the wrong side of the law unnecessarily.

“The system is too rigid, especially the requirements for degrees,” says Li Qing, an associate researcher at the Center for China and Globalization, a Beijing-based public policy think tank. “There should be a flexible mechanism that takes market demand, experience, and skills into consideration.”

Though he agrees that training centers should be required to share information on all teaching staff in order to ensure student safety, Li says the government should use more innovative methods to assess foreign teachers.

“There can be different skill requirements for foreigners working in different positions,” says Li. “For educators teaching oral English, the assessment should focus on their speaking skills.”

Any changes would come too late to help Jay, however, who is now volunteering at a children’s home in South Africa. She says she still misses her former colleagues and students, but when asked whether she would consider returning to King’s for a third time one day, she doesn’t hesitate: “Probably not.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

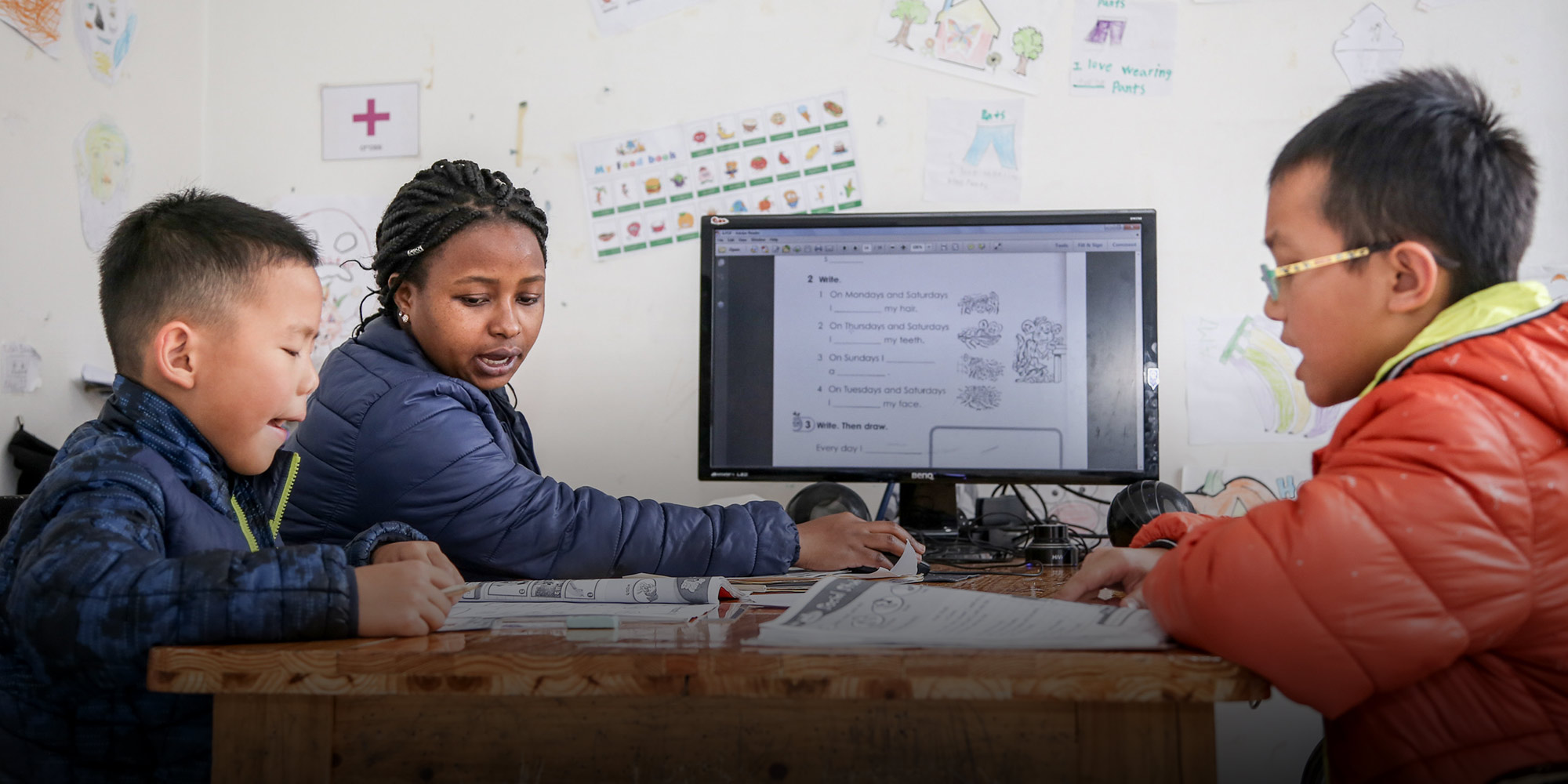

(Header image: A foreign teacher instructs her students during an English class at an after-school training center in Kunming, Yunnan province, Oct. 13, 2018. IC)