Visions of Gods in a Chinese River Town

ZHEJIANG, East China — Literary types have been seeing deities on the banks of the Yangtze River for more than two millennia.

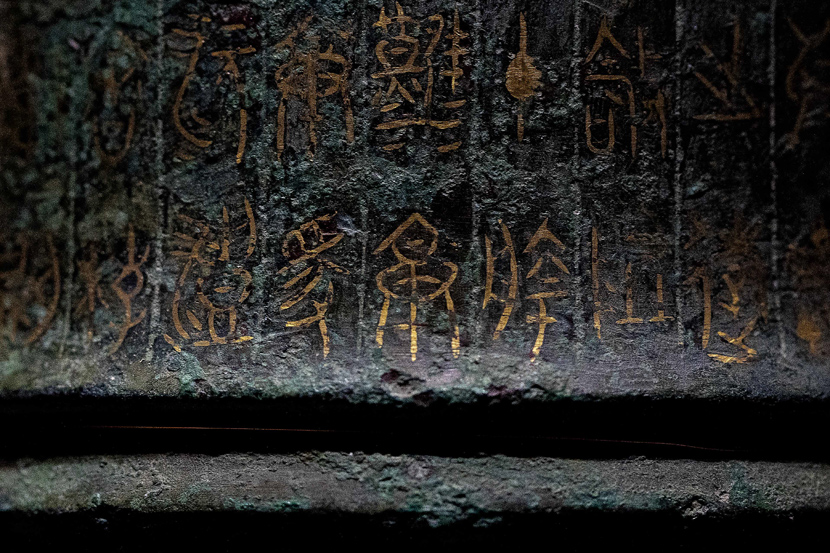

First came Qu Yuan, the poet and politician said to have written the classic “Nine Songs” — a collection of hymns to divinities and fallen soldiers — while exiled to a river town on the Yangtze around 2,300 years ago. Centuries later, the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) painter Chen Hongshou created delicate portraits of these same gods in his own “Nine Songs” series.

Tang Xiaosong is the latest Chinese artist to answer the river deities’ siren call. His first exhibition, a multimedia project titled “The Skiff,” brims with references to the Yangtze’s cultural heritage.

For the 43-year-old, the return to the “Nine Songs” — one of the wellsprings of Chinese literature — is deeply personal. Tang was born and raised in a village just outside Yichang, a riverside city in central China’s Hubei province, which is located just 24 kilometers from Qu Yuan’s birthplace. But he had spent much of the previous two decades working in Beijing as an editor at men’s magazines including GQ and Esquire.

Tang seemingly had it all — a high-flying, glamorous career in the Chinese capital — but one trip to Mount Putuo in 2013 convinced him to give it up. After staying overnight at a temple on the sacred Buddhist pilgrimage site, Tang decided, in his words, to “leave the world of celebrities and luxury.”

The former journalist turned to art as a way to rediscover “his sensitive self,” he tells Sixth Tone. At first, Tang struggled to find an outlet for his creativity, but then he attended a workshop by the celebrated photographer Shen Wei.

Shen’s work, with its persistent theme of capturing a sense of loss amid a rapidly changing society, made an instant connection with Tang. Though he had no experience as a professional photographer, Tang decided to make photography his main medium. “I found that what inspired me first was what I saw,” he says.

Tang returned to Yichang and began shooting. For him, the trip not only represented a return to his hometown, but also to an earlier period in his own life and even in Chinese history.

“I realized the changes happening to the Chinese people right now may be more dramatic than any changes that have ever take place within the same period of time in human history,” says Tang.

For Tang, the past appears as a purer place of which only traces remain. His lens constantly seeks out glimpses of this lost world amid the drab urban landscapes of Hubei: a bunch of fishing rods swaying in front of a gray suspension bridge or a single boat drifting on a lake among a ring of looming tower blocks.

This attitude is understandable. The physical landscape in much of Hubei is almost unrecognizable compared with 30 years ago. The village where Tang grew up is now underwater, submerged following the construction of the Three Gorges Dam.

“(The change) is dramatic, but just like the stones scoured smooth by the waters of the Three Gorges,” says Tang, “nothing can be cruel in the eyes of a poet.”

Tang’s sense of loss upon his return to Yichang helped him find new meaning in the “Nine Songs,” he says. “The Skiff” repeatedly alludes to the ancient work. In one series of images, Tang even directly superimposes wispy shadows of Chen Hongshou’s woodcut gods onto photographs of the sky.

“I think one of the essential themes in Qu Yuan’s poetry is waiting for someone who will never come,” says Tang.

For the photographer, the image of each god calls to mind a certain passage from the “Nine Songs.” A print of Shao Siming, for example, evokes the lines, “I looked for you, beautiful one, but you never came. I sing facing the wind in loud despair.” The image of Xiang Furen, meanwhile, makes Tang think of another passage: “I narrow my eyes to see him — it saddens me. In light gusts comes the autumn breeze. Waters of Lake Dongting ripple under leaf fall.”

The exhibition, which was held this fall at the China Port Museum in Ningbo, Zhejiang province, is Tang’s attempt to freeze these transcendent moments in time. Even the worn yellow sofa that sits in the center of the hall has its own link to a bygone age.

The Naples sofa, made in 1982, belonged to Tang’s maternal grandparents and contains countless memories of his childhood, he says. But the golden cranes covering the upholstery also symbolize the immortals in ancient Chinese folklore. Tang recites a poem by Cui Hao, the Tang dynasty (618-907) poet, to explain its significance to him:

Once upon a time an immortal flew away on the back of a yellow crane,

What remains of the tale here is a tower bearing its name.

The heavenly creature once gone has never returned,

For thousands of years white clouds have in the skies drifted in vain.

Note: Translations of passages from the “Nine Songs” are taken from Gopal Sukhu, “The Songs of Chu: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poetry by Qu Yuan and Others” (2017). The translation of Cui Hao’s poem, “The Tower of Yellow Crane,” is by Betty Tseng.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: “Xiang Jun,” the ruler presiding over the Xiang River, from the “Nine Songs” series in the project “The Cliff.” Courtesy of Tang Xiaosong)