Woman in the Dunes: Sanmao’s Life and Legacy

Echo Chen was 31 when she made up her mind to move to Africa. Always a writer and a romantic, the Chongqing-born, Taiwan-raised young woman had been biding her time in Madrid again, aching for freedom and adventure. Soon she would settle in the last vestige of the Spanish Empire. Residing in the town of El Aaiún, in what is now the disputed territory of Western Sahara, she adopted the pen name by which she would become known as one of the most striking figures in modern Chinese literature.

In October 1974, dispatches from the Spanish Sahara began appearing in Taiwan’s United Daily News, attributed simply to “Sanmao.” This pseudonym recalled the iconic cartoon character popularized decades earlier by illustrator Zhang Leping: a Shanghai street urchin named for the three lonely hairs on his head.

Sanmao’s newspaper vignettes set the domestic and the mundane against the stark and otherworldly backdrop of the Sahara. As narrator and protagonist, Sanmao toils away in the kitchen, attends to laundry and household chores, and vies to get her driver’s license. But just as often, she finds herself fending off thugs in a swampland, chasing down UFOs, or falling prey to a cursed necklace. Her Spanish husband José is by turns savior, conscience, and unwilling accomplice. Together they navigate the politics and bureaucracies of Spanish Africa, forge friendships with their Sahrawi neighbors, and in her words, “make a home from scratch.”

The first edition of Sanmao’s “Stories of the Sahara” anthology was published in Taiwan in 1976, where it quickly sold out of several successive printings. In her forward to my English translation, published earlier this month by Bloomsbury, writer Sharlene Teo posits that Sanmao’s “unabashed self-aggrandizement” may have presaged the egocentrism rampant in today’s social media landscape. Her marital life and daily banter with José threads throughout the collection of stories, depicting an intercultural relationship “both glamorous and mundane, deeply romantic and humorously practical.”

One could shrug her off as an archetype, a manic pixie dream girl, or a glitzy anachronism. But the truth is that freewheeling and internationally mobile women from Asia were few and far between back then; as such, Sanmao wielded outsized influence on her legions of fans. Hindsight also forces hard truths on the contemporary reader: the successive tragedies that shadow the liveliness of Sanmao’s prose, as well as the bizarre rumors about her life and stories that persist to this day.

In Taiwan, Sanmao made a name for herself as a female writer with remarkable candor and an astute grasp of narrative, paired with a larger-than-life persona. She was known as the woman wanderer in the desert, capable of charming or outwitting strangers at every turn. According to New York-based writer Manchuang Nadia Ho, Sanmao’s entree into the literary scene rocked the patriarchal and conservative sensibilities of 1970s Taiwan, then still under the grip of authoritarian rule.

Married to a foreigner, reveling in her independence and agency in distant lands, Sanmao eschewed conformity in favor of free-spirited cosmopolitanism. She sought meaning and connection in her encounters with lovelorn store clerks or hapless sojourners, desert nomads, and fearsome soldiers. That she would continue to center and reveal so much of her own personal life in her stories was an affront to some readers — and a delight to many more.

Although her prose and public persona both have their detractors, Sanmao’s appeal has proved lasting. Her readers in the ’70s and ’80s lived vicariously through her tales during a political era when few people could travel so far and wide. Meanwhile, she continues to be idolized by young women in particular, many of whom call themselves “Echo” in homage to the name by which she was known to José and her non-Chinese friends.

Sanmao represented values of “freedom, curiosity, and (belief) in … human kindness” for her contemporaries, says Ivy Ma, a financial professional in New York who first read “Stories of the Sahara” when she was about 13. Decades of economic development and the globalization of higher education have made a journey like hers much less remarkable, if not commonplace. But Ma says that reading Sanmao may have encouraged her to embrace a sense of openness to the world, perhaps even planting the early seeds of her dream to one day live and settle abroad.

As the Spanish Sahara convulsed with political unrest, Sanmao and José evacuated to Gran Canaria, an island roughly an hour’s flight from the African mainland. They made their home in Telde, the town where Sanmao would write her next volume of slice of life tales, titled “Notes of a Scarecrow.”

Their sleepy life on the island would not outlast the decade. José died in a freak diving accident in 1979, and Sanmao eventually returned to Taiwan and threw herself into her work, taking on all manner of projects — university teaching, writing songs and screenplays, and translating from Spanish into Chinese, all while continuing to publish prolifically about her life, her travels, and her worldviews.

At the height of her career, Sanmao had transformed into a cultural commodity herself, as the Australian scholar Miriam Lang once contended. “She was a product of the mass media,” Lang wrote in her Ph.D. dissertation. “And yet presented as an individual largely untouched by commerce, a spontaneous free spirit motivated by feeling.” Lang believed that it was precisely because her readers could project their own values onto her celebrity persona that they grew to love her as an aspirational “fantasy self.”

The public sphere has long been unkind to women who transgress social or cultural norms. A number of Sanmao’s male contemporaries set out to debunk what she claimed were truthful or autobiographical accounts. Some railed against supposed embellishments about her background or her relationships. Others advanced even more outlandish claims: that her husband never existed, that everything Sanmao had ever written was pure fiction. Even today, nearly three decades after her suicide in 1991, these whispers still haunt her legacy.

Even so, her charm has transcended linguistic and cultural boundaries in just the manner that would have pleased her. Almost half a century after Echo initially moved to Africa, assuming the mantle of Sanmao in the process, a recent spate of new translations into Spanish, Catalan, Dutch, and English are introducing this extraordinary woman to millions more readers around the world. Writing had been a salve for her loneliness, a means to inscribe logic and order onto a disorienting, at times dehumanizing, reality. Now, those words have allowed her to breach the ultimate boundary and gain new fans who are falling under the spell of her earnest warmth and compassion.

“Everyone saw this kind of yearning in her,” says Echo He Yu, owner of the Fou Gallery in Brooklyn. “She sought until she could no longer seek. Then she continued to seek.”

Editors: Hannah Lund and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

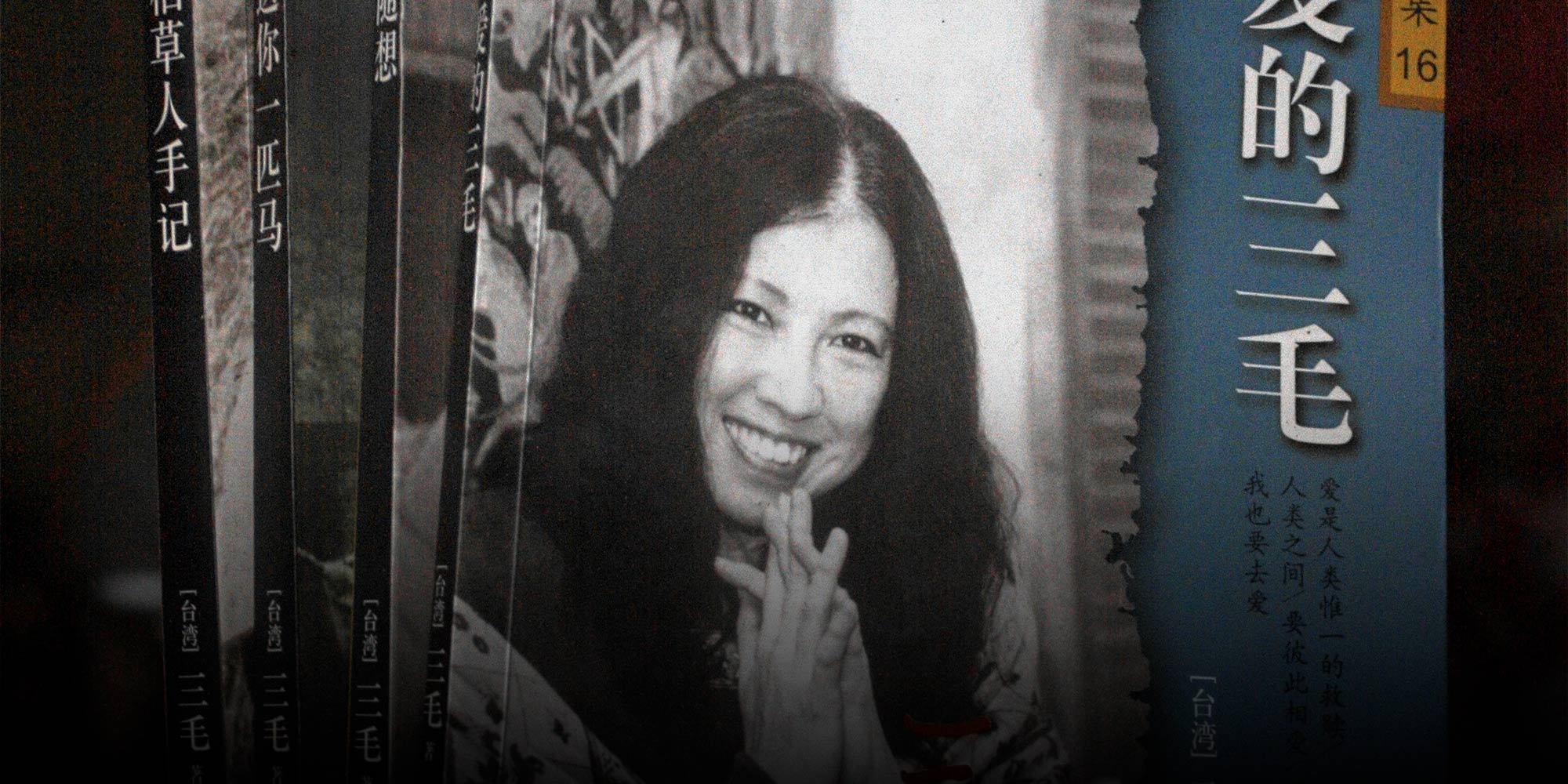

(Header image: Sanmao’s works on display in her birthplace of Chongqing, Jan. 7, 2011. Tuchong)