Four Charts That Help Explain How the Coronavirus Spread

On Jan. 12, a longtime resident of Huanggang, a city in China’s central Hubei province, caught a train to Zhuhai, on China’s southern coast.

She arrived the next morning with a nagging cough, but wrote it off as a cold. A week later, her symptoms worsened. She checked into a Zhuhai hospital on Jan. 19, and at 10 p.m. on Jan. 21, she finally got a diagnosis: the novel coronavirus.

At that point, Huanggang had reported just 12 cases of the disease. Today that number stands at 1,897, making the city one of the hardest hit in an epidemic that as of Feb. 7 has already killed 637 and sickened 30,000 more on the Chinese mainland since it was first identified in Hubei provincial capital Wuhan last December.

There were suggestions of human-to-human transmission from almost the very start of the outbreak. But as late as Jan. 19, Wuhan’s health authorities were still reassuring residents the risk was “relatively low.” It wasn’t until the next day, when Zhong Nanshan — a doctor renowned for his work during the 2003 SARS epidemic — declared the evidence for human transmission “definite,” that officials finally began to take it seriously. Two days later, they shut down all buses, trains, and planes in and out of the city.

It was too late. An estimated 5 million Wuhan residents had already left the city ahead of the country’s weeklong Lunar New Year holiday. Most of them dispersed across the province, to cities like Huanggang or remote villages to celebrate with their families. Others went on vacation to places like Zhuhai or the eastern city of Wenzhou.

The novel coronavirus has an incubation period of up to 14 days, meaning those infected might not have even realized they were carrying the disease when they set out on their journeys. By the end of January, there were confirmed cases in every province-level region in the country.

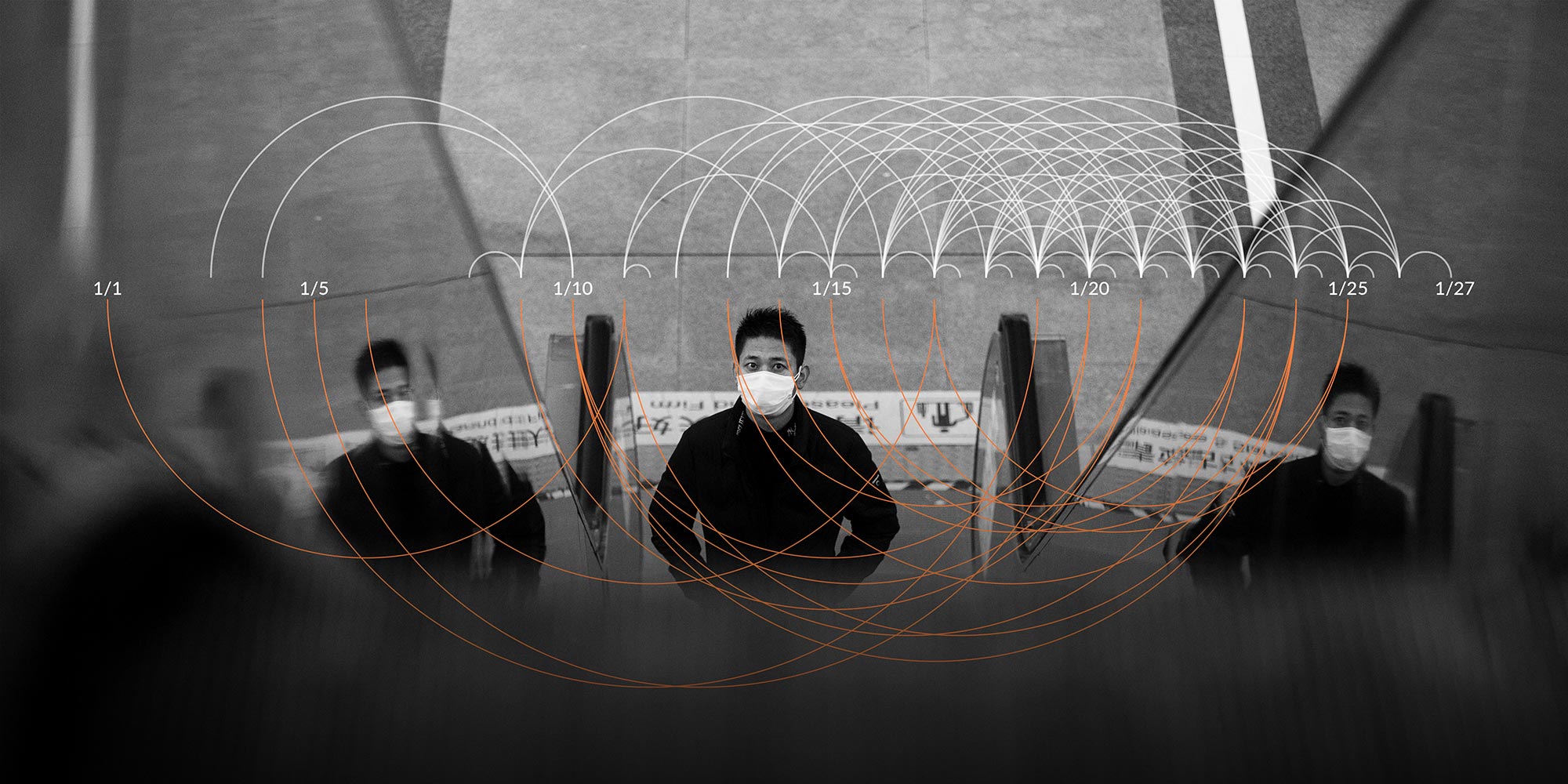

To get a clearer picture of how the virus spread, reporters at Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, analyzed the 763 novel coronavirus cases confirmed before Jan. 28 — a week after Zhong’s warning — for which detailed information is available. The results not only allow us to trace the path the virus took across the country, but also offer a powerful reminder of the importance of information transparency to a healthy society.

Editor’s note: Differences in the amount of publicly available data for each region make it hard to draw comparisons across regional lines.

On the night of Jan. 22, the Wuhan municipal government announced it was closing all airports, train stations, and other mass transit in and out of the city beginning from 10 a.m. the following day.

The decision came just two days before the start of the Lunar New Year holiday, a time when hundreds of millions of Chinese travel home or abroad, attend banquets, and convene with their loved ones. Of the 506 analyzed cases in which the patient’s full itinerary is known, 368 left Wuhan in the week before the quarantine. Of these, 86% did so prior to Jan. 21, when the authorities belatedly began warning of human-to-human transmission.

One carrier, a resident of northern Hebei province, arrived with his parents in Wuhan on Jan. 15. The three tourists left for the southeastern city of Xiamen three days later. Although the son began to experience symptoms on Jan. 19 — one day before Zhong Nanshan sounded the alarm — they continued their trip. He finally went to a hospital immediately after arriving in the southern megacity of Shenzhen on Jan. 22.

Many of those who left Wuhan in the days leading up to the shutdown had similar experiences. Of the 506 known itineraries, at least 47 included multiple cities after leaving Wuhan. Another 28 never entered the city, instead contracting the disease while visiting other parts of the province. And a few never went to Hubei at all: They were infected after coming into contact with carriers elsewhere.

Of the 67 patients who passed through Wuhan on their journeys, 17 stayed only one day, and another four spent just hours in the city. There does not appear to be a connection between travelers’ length of stay in the city and the possibility of getting infected, greatly increasing the difficulty of identifying potential carriers.

“Everyone has been dissatisfied with our information transparency in this outbreak,” Wuhan’s mayor Zhou Xianwang told China’s state broadcaster in an interview on Jan. 27.

The importance of timely, authoritative updates in an epidemic can be seen from the intervals between when patients first felt ill and when they sought treatment. In the early stages, a novel coronavirus infection can closely resemble a common cold, and many patients — and even some doctors — were unaware of the potential severity of the disease.

One patient, a longtime Hubei resident from the northwestern Shaanxi province, first became symptomatic in late December but didn’t seek treatment from the local hospital until Jan. 21, after Zhong Nanshan’s announcement brought greater attention to the epidemic.

The broader data shows a split between those who started showing symptoms prior to Jan. 18 and those whose symptoms appeared after — with the former waiting much longer on average before seeking treatment. The contrast becomes even sharper on Jan. 22, when there was a noticeable jump in the number of patients seeking treatment the day their symptoms showed.

What changed on Jan. 22? That was the day the Hubei provincial government finally declared a public health emergency. Within a week, every other province-level region on the Chinese mainland would follow suit.

Contributions: Zhang Yijun, Chen Liangxian, Wang Xujing, Li Hongying, and Zhao Yanan; translator: Kilian O’Donnell; editors: Liu Chang, Fu Xiaofan, and Hannah Lund.

(Header image: Photo taken by Yi Chuan; edited by Fu Xiaofan/Sixth Tone)