A Brief History of Face Masks in China

It’s usually not a good sign when the most in-demand accessory of the season is a face mask. With China battling an outbreak of a novel coronavirus — the newly named COVID-19 — that has already killed 1,114 and sickened 44,000 as of Feb. 12, face mask factories around the country have been working overtime for weeks to keep up with demand. Yet supplies remain scarce enough that local governments are requisitioning shipments bound for other cities, and residents in some areas need to register for state-issued vouchers if they hope to get their hands on some.

Between widespread air pollution and the occasional infectious disease outbreak, images of Chinese people in face masks have become a kind of visual shorthand for some of the problems that have emerged over the past 40 years of breakneck development. Yet for all their seeming ubiquity, convincing the public to actually wear the masks is an ongoing project. In the early days of the current outbreak, netizens left a wave of online comments complaining about the difficulty of getting their parents and older relatives to put on masks when going out. The masks you do see on China’s streets are products of a conscious, centurylong campaign to improve national hygiene and health standards.

Long before the development of anything that resembled a face mask, Chinese simply covered their mouths with either their sleeves or hands. This method was both unsanitary and occasionally inconvenient, however, and the more affluent eventually started using silk cloth instead. In the 13th century, Italian explorer Marco Polo recounted how servants in the Yuan dynasty court were required to cover their noses and mouths with a cloth of silk and gold thread when serving food to the emperor.

The surgical masks in use today are a Western import. The use of masks in medical procedures dates back at least to 1897, but they were not widely adopted by the Chinese medical community until the early 20th century.

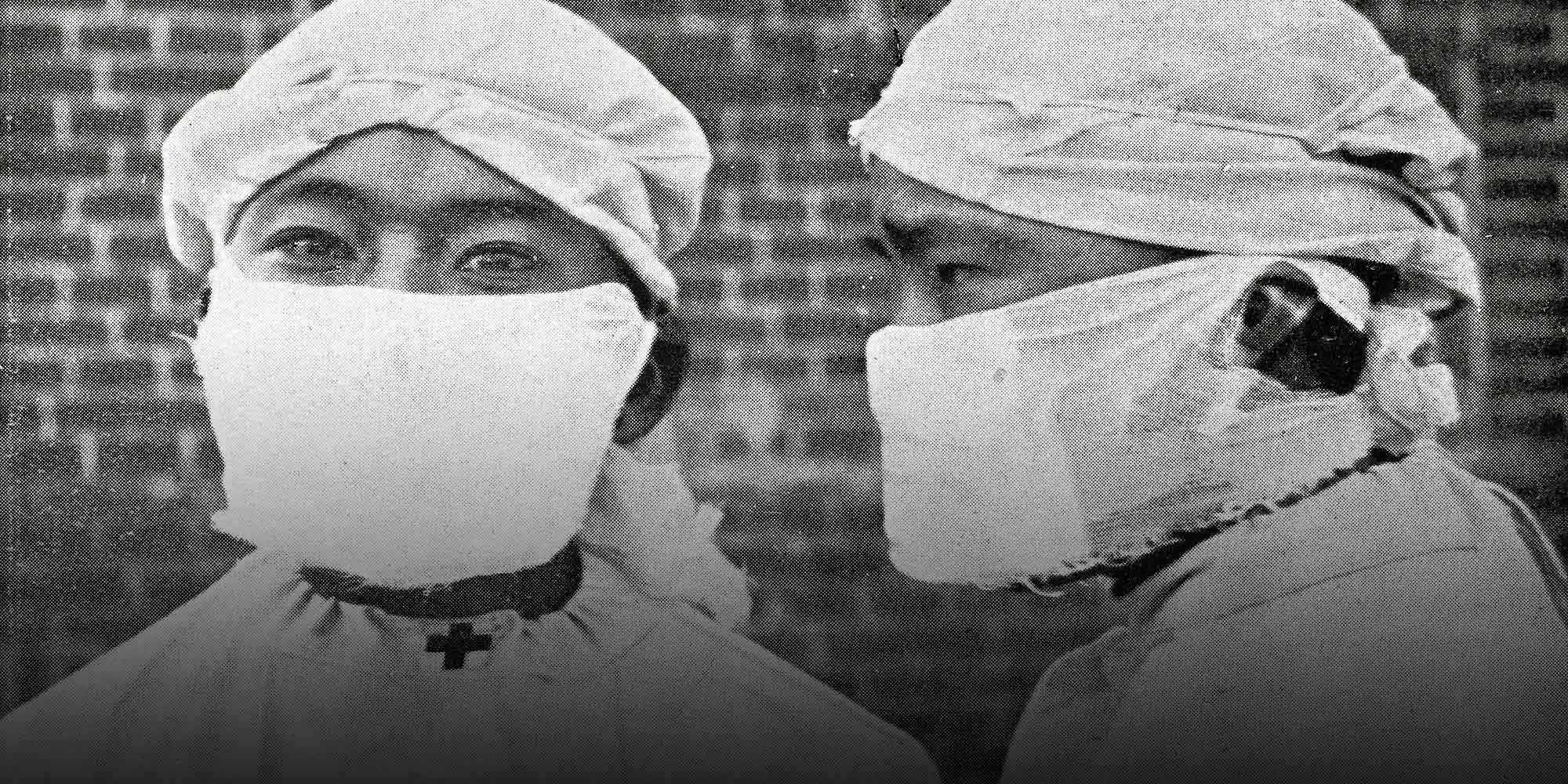

In late 1910, the legendary Malaysian-Chinese doctor Wu Lien-teh was serving as China’s chief medical officer when an epidemic broke out in Northeast China. Wu went deep into the affected areas to lead prevention and control work, and soon identified the epidemic as a form of pneumonic plague spread by droplets in the air. In addition to proposing now-familiar-sounding measures — including quarantining patients and cordoning off many cities — Wu also designed and invented a cheap sanitary face mask that promised some protection from the disease. Made of widely available surgical gauze folded around a 4-by-6 inch piece of cotton, it could be wrapped around the back of the head and tied in a knot. Simple and easy-to-make, it was affordable enough for almost anyone to buy.

China’s doctors and nurses continued using Wu’s design throughout the 20th century, improving it here and there but making no substantial changes. It wasn’t until the 2003 outbreak of SARS, which infected hundreds of medical workers and showed the limitations of traditional cotton masks, that the then-China Food and Drug Administration retired Wu’s mask in favor of newer, more effective models.

But medical professionals aren’t the only Chinese to routinely wear face masks. During the Republican era (1912-1949), China experienced wave after wave of cholera, smallpox, diphtheria, typhoid, scarlet fever, measles, malaria, and dysentery. Shanghai saw 12 outbreaks of cholera between 1912 and 1948, six of them major. In 1938 alone, the city reported 11,365 cases, and 2,246 people died.

As far as the country’s health authorities were concerned, one of the easiest and cheapest means of preventing these outbreaks was getting people to wear masks. In 1929, the government responded to a meningitis outbreak that began in Shanghai and soon swept across the entire country by encouraging citizens to don masks and avoid public gatherings. Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, in China’s then-capital, sold face masks to public servants and ordinary residents alike. In small towns like Pinghu in the eastern Zhejiang province, residents could collect face masks for free.

In cosmopolitan Shanghai, face masks were promoted as fashion accessories to encourage their use. In response to the meningitis outbreak, well-known journalist Yan Duhe discussed the importance of wearing masks in a 1929 column for the newspaper Xinwen Bao titled, “The Most Fashionable Spring Accessory: A Black Face Mask.” In it, Yan suggested that drugstores should set aside profits and sell items necessary for epidemic prevention, including masks, at cost.

He also recommended the government recruit famous celebrities and socialites to wear masks at spring fashion shows as a means of boosting popular acceptance. Contemporary magazines often portrayed women in masks as exemplars of good hygiene, turning the coverings into a status symbol connoting membership in the city’s educated upper crust. Other outlets produced tutorials that taught housewives how to knit their own wool masks to use in the winter.

With the onset of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937, face masks became essential protection against chemical and biological warfare. Magazines such as the Red Cross Society of China Newsletter, Air Defense Monthly, and Student Magazine began publishing articles on how to improve face masks by dousing gauze in chemicals like urotropin, sodium carbonate, and ammonium thioate — a combination that would supposedly provide protection against poison gas.

The evidence is mixed as to whether masks — even high-tech variants like the N95 — provide protection against COVID-19. But over the past century, Chinese have relied on face masks to shield them from disease, chemical warfare, and pollution. In the absence of better options, we may have to do so again.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: A photo tutorial showing how gauze-cotton masks should be worn, in “History of Chinese Medicine,” by K. Chimin Wong and Wu Lien-teh, 1934. From Wellcome Collection)