Online Classes Get Mixed Reactions From Students, Teachers

Update: On March 2, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology issued a notice urging domestic telecom companies to improve network coverage in rural areas and offer discounted data plans to students from low-income households.

Millions of Chinese students are starting a new school term not in their classrooms, but in front of their computers.

Weeks after schools delayed the spring semester due to the ongoing COVID-19 epidemic, China’s education ministry in late January ordered institutions to continue administering coursework online. Daily activities including flag-raising ceremonies, roll calls, and lectures are now conducted virtually.

Wang Lufeng, an associate professor of food science at Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan, the central Chinese city at the heart of the epidemic, told Sixth Tone that he has been livestreaming lessons to his 62 students. To get a better signal in his rural hometown in the eastern Shandong province, the professor said he has to lecture from his roof.

“It’s normal,” Wang said. “A majority of teachers in our school have started to give online courses.”

But an increase in demand for livestreaming and other online education services is causing app crashes and other internet disruptions, with several related hashtags including “Tecent Classroom crashed” trending on microblogging platform Weibo.

“I wait from 8 a.m. until noon, feeling like a century has passed,” a college student complained on Weibo, referring to frequent disruptions during live lectures.

Many online education platforms including Rain Classroom, Superstar Study System, and China University MOOC apologized for poor service on Monday, naming the surge in users as the chief cause.

“The number of concurrent online users on the platform is about 10 times higher than usual, resulting in system overloads and platform instability,” China University MOOC wrote on Weibo. The education platform recommended that students log in during non-peak hours when possible.

With distance learning on the rise, education experts are questioning whether online courses are necessary for everyone, from primary schoolers to university undergrads.

“Students require autonomous learning abilities for online education,” said Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute, a Beijing think tank. “Meanwhile, spending too much time online could affect students’ eyesight, and is not conducive to the cultivation of their learning habits.”

For many students, access to computers and the internet has also posed challenges for continuing online classes.

A student surnamed You at Anhui Agricultural University told Sixth Tone that she hasn’t been able to take classes regularly due to a spotty internet connection at her home in rural Fujian province, and because using cellular data is “extremely expensive.”

“It’s hard to take online classes in a rural village,” You said. “Broadband connections aren’t common here. Not every family has a smartphone.”

Xiong told Sixth Tone that online courses cannot reduce the educational divide between urban and rural areas — and in fact may even be counterproductive.

“In addition to poor rural internet access, rural children more importantly lack sufficient family supervision and guidance,” he said. “Providing them with online resources doesn’t mean that they will learn. The gap between urban and rural children may even widen.”

Editor: Bibek Bhandari.

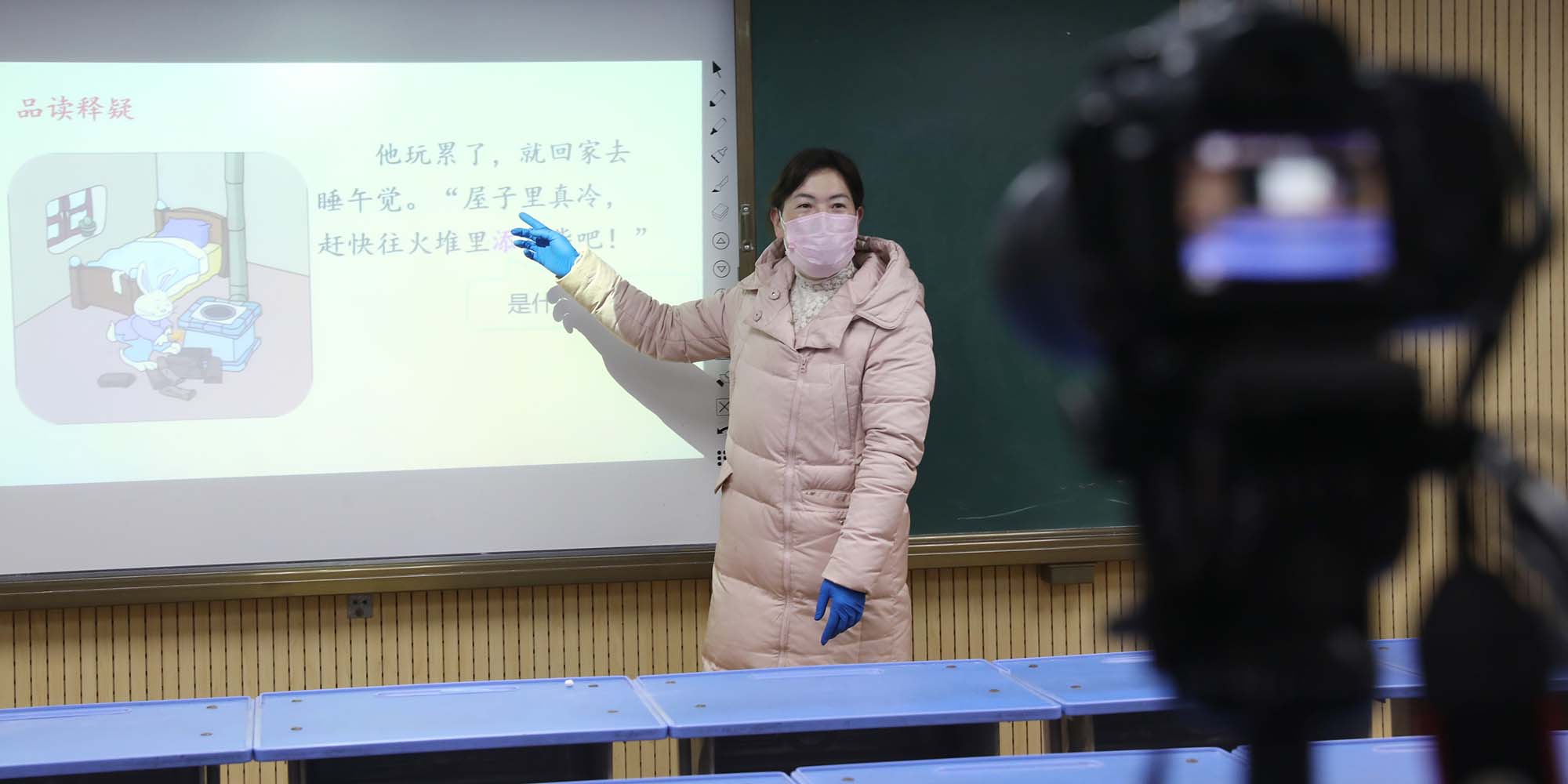

(Header image: A teacher leads a livestreamed class for primary schoolers in Jiaozuo, Henan province, Feb. 10, 2020. Xinhua)