How COVID-19 Changed the Conversation About Chinese Journalism

On Feb. 26, Caixin, a Chinese media outlet with a well-earned reputation for high-quality reporting, published an in-depth investigative report on the Chinese researchers who had identified key warning signs of the current pandemic as early as December 2019 — only to watch as their work was flushed down a bureaucratic black hole for weeks.

That same week, another prominent Chinese news outlet, Caijing, published an exclusive exposé of its own, detailing how local officials had allegedly obstructed the work of a national investigation team sent to the emerging outbreak’s epicenter in early January. The article’s sources did not mince words, outright accusing their local interlocutors of “lying.” The piece was viewed millions of times on social networking platforms like Weibo and WeChat.

The past few years have been a trying time for China’s journalism industry. As a teacher at a journalism school, I’ve seen firsthand how these trends have caused my students to question their professional futures, but I also believe the current crisis proves there’s still room for real reporting in our society.

The ongoing spread of COVID-19, which the WHO March 11 declared a pandemic, has ironically offered a sort of proof-of-life for several once-prominent Chinese media companies. According to one analysis, since Jan. 20, a total of 13 market-oriented outlets have sent journalists to the central city of Wuhan, where the outbreak was first reported late last year.

Although Caixin has arguably gotten the most attention, a number of other respected but long-torpid publications, including China Newsweek and Sanlian Life Week, have also published detailed, hard-hitting reports from Wuhan. They’ve covered everything from residents going untreated as hospitals struggled to cope with a deluge of patients to malfeasance and incompetence at a local Red Cross Society of China branch.

These outlets’ outstanding performances have given a needed boost to the country’s traditional media industry. At the turn of the 21st century, journalism — especially investigative journalism — was both a haven for idealism and a lucrative pursuit. Those days are long gone, in part thanks to regulations as well as competition from digital outlets. Public reactions to the journalistic work being done in Wuhan, however, offers new hope for outlets willing to conduct in-depth reporting.

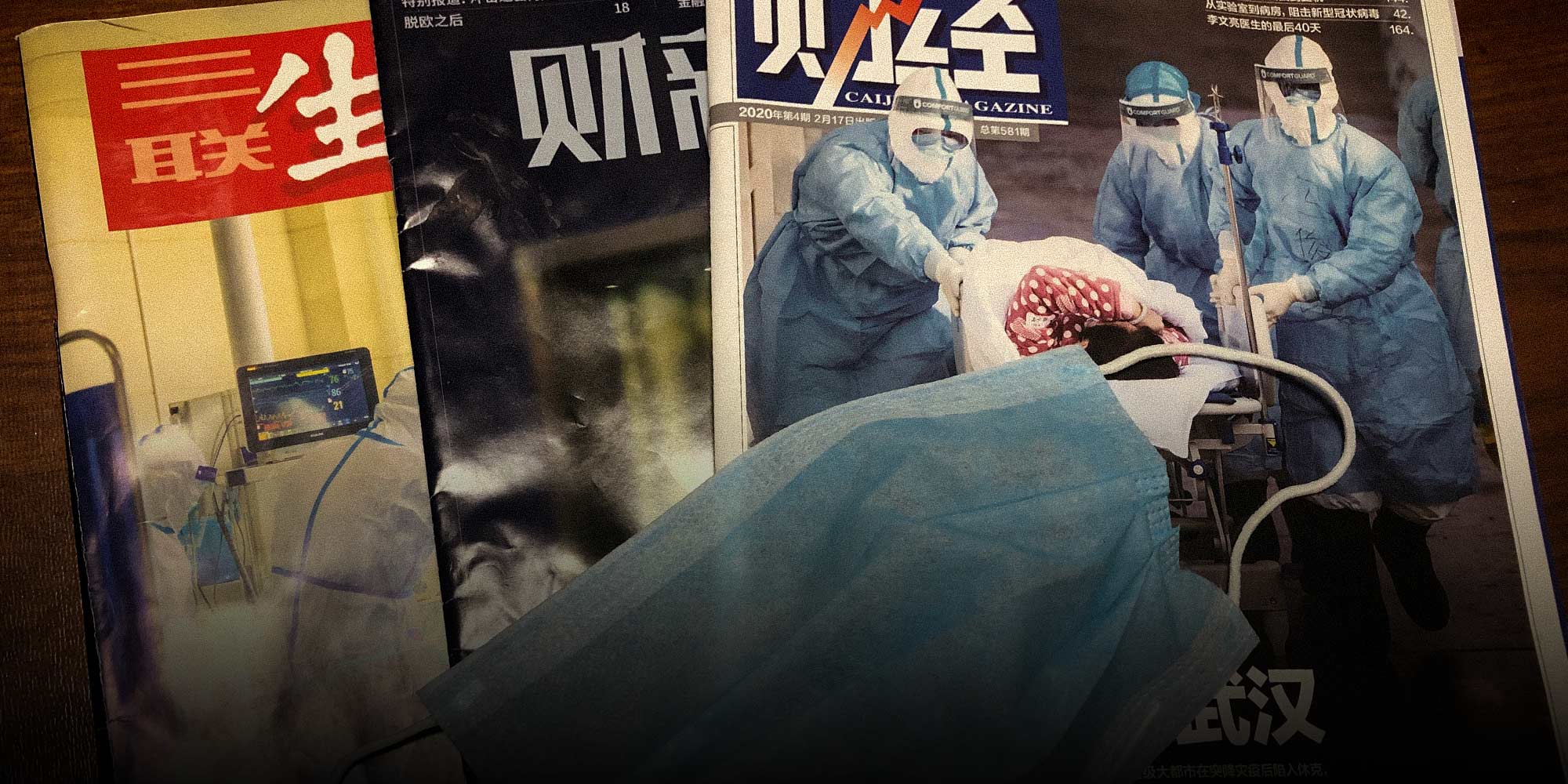

Take Caixin, for example. Although it removed its paywall for reports linked to the pandemic, readers have found other ways to support the company. When its weekly print magazine published the first two parts of a three-issue series on the pandemic and response efforts, they sold out almost immediately, and the company quickly announced plans for a secondary print run. Anecdotally, several members of chat groups I’m in have purchased every print issue that Caixin and Sanlian Life Week have published about the crisis, partly for historical purposes and partly to memorialize those who’ve died.

Meanwhile, from my vantage point within academia, the recent performance of China’s journalism industry offers a vociferous rejoinder to doubts about the importance of reporting in the “post-truth era.”

Chinese students and scholars of journalism are suffering from an identity crisis. What’s the use of upholding professional standards such as fact-based reporting and objectivity when all audiences seem to want is sensational content that reinforces their preexisting notions about the world? I’ve lost track of how many debates I’ve witnessed at conferences, seminars, and forums over the value and viability of professional journalism: Is it still necessary? Will it be replaced by social media or citizen journalism? Can the industry even survive?

These anxieties are not unique to China: Together, they comprise what I like to call the “post-truth syndrome.” But the debate has added significance in China, where only media organizations certified by the state are authorized to report on issues of social or political importance. Done right, grassroots WeMedia outlets can play a useful role in keeping the public informed, but they lack certifications, as well as access to the kinds of authoritative sources open to professional journalists.

This ultimately limits their usefulness in times of crisis. We face a century likely to be filled with uncertainty and risk, whether natural or man-made. To meet them, we need to cultivate dedicated, professional media organizations capable of carrying out challenging investigative reporting under difficult circumstances. That doesn’t mean social media and citizen journalists don’t have a role to play, but if grassroots journalists are the foot soldiers of the future journalism industry, outlets like Caixin are the special operations forces.

Training these troops should be the primary goal of journalism education. A competent journalist must be equipped to sniff out useful information from a variety of sources, have the sensitivity to navigate China’s challenging political and regulatory environment, and ferret out the truth based on conflicting, entangled narratives. This cannot be achieved through courage and passion alone. It takes tedious and repeated practice, ideally in an educational environment, where practitioners can get guidance from experienced teachers.

In a previous piece, I wrote: “The value of journalism is not fading, even though traditional media seems to be deteriorating. Decline also foreshadows revival, and in my journalism class, I’ll do my utmost to prepare them (my students) for its future renaissance.” Last year, for example, I organized a new student group at my university to assess various media outlets on the basis of diversity, balance, transparency, and logical coherence.

At the time, a friend of mine joked that quality no longer mattered in journalism — all that counted was clicks. I’d like to think that the events of the past month definitively show that is not the case.

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Wang Xuanhui for Sixth Tone)