Notes on COVID-19 and the Abrupt Digitization of Learning

I have been an associate professor at China’s Zhejiang University for over a decade, but the current semester — only a month old — has presented even an experienced teacher such as myself with plenty of novel challenges. On the very first day of class, I was sitting in front of my computer, trying to focus on the screen in front of me, when out of the corner of my eye I saw my elementary school-aged daughter sneak into my room and strut around. In that moment, it was like my brain short-circuited: I suddenly knew exactly how “BBC Dad” Robert Kelly must have felt during his famous interview.

With schools across China temporarily unable to open their doors because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Education in late January unveiled what it termed its “suspending school, not learning” policy. Among other proposals, the policy called for a massive expansion of online teaching at all levels.

By the time my university started online classes on Feb. 24, I was already familiar with some of the different platforms available: Primary schools in Zhejiang had started about a week prior, and I had sat in on some of my daughter’s virtual lessons while she got accustomed to the new system.

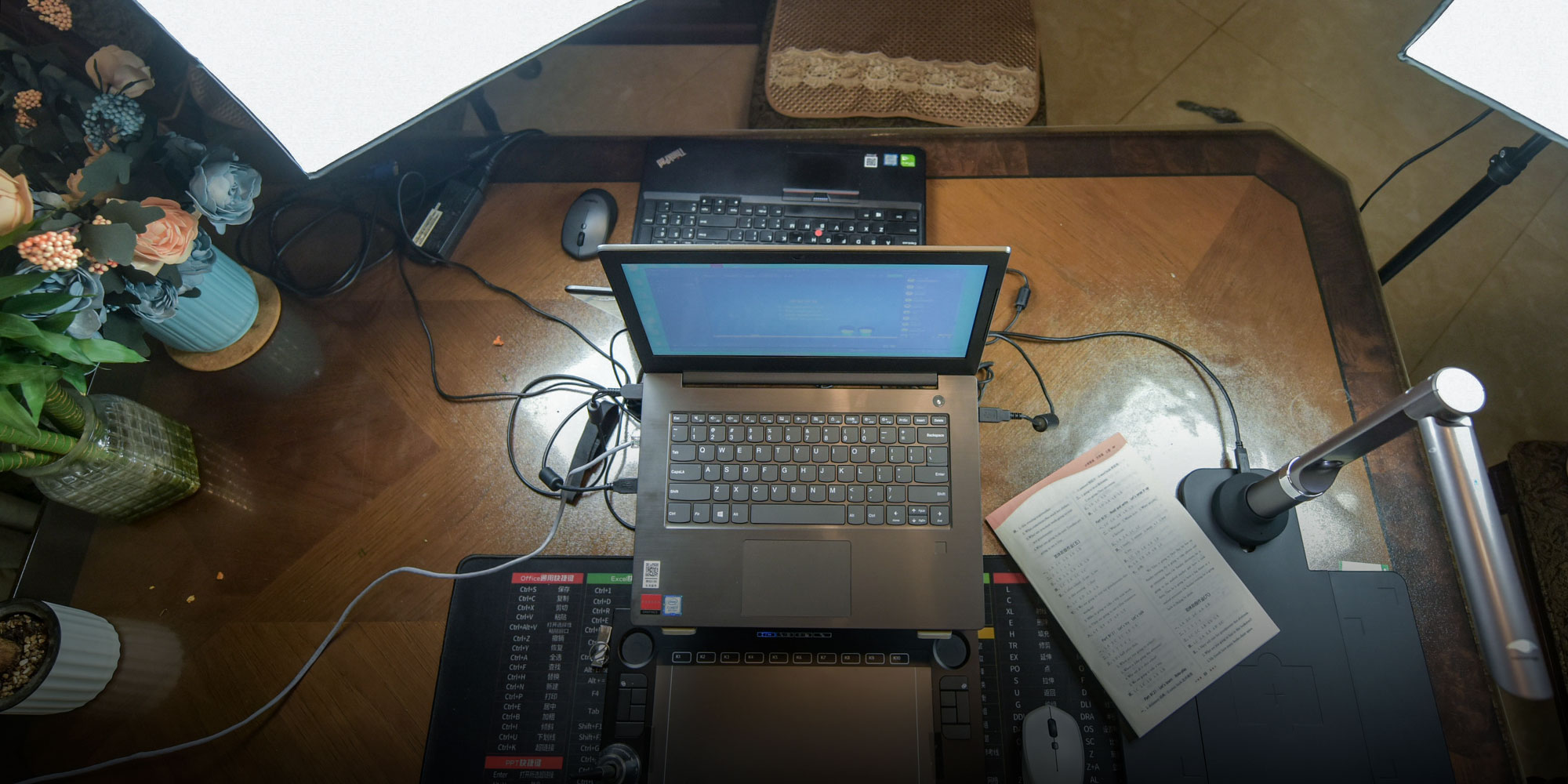

So instead of worrying about the technical side of things, I was more concerned with how I was supposed to squeeze a makeshift recording studio into my family’s tiny living quarters. I already felt like I was living in a miniature internet café: My daughter had to take classes online; my wife was telecommuting and participating in frequent conference calls; and now I was expected to be a livestreamer. But after spending three afternoons a week lecturing into the empty air of my bedroom, I do think I have a better understanding of what the digitalized future of teaching the humanities may look like.

The first thing I noticed was that online teaching lacks the usual sense of ritual and focus of the classroom. I was struck by how a seemingly simple spatial shift — moving from one’s home or dormitory to a classroom, for example — could help solidify a corresponding shift in social roles from civilian to student or teacher. You lose this feeling when classes are held online. For teachers, the journey becomes a walk from your bedroom to your living room or study, or vice-versa, in my case; for students, perhaps from their bed to their couch or desk. (Though I did notice some students opting to partake in class directly from the comfort of their mattresses.)

Online teaching also has a way of removing the most basic human and emotional exchanges from the classroom atmosphere. Although I don’t consider myself a controlling classroom manager, I miss the silent communication of the lecture hall.

I’m not sure if this is a cultural thing or not, but in China, at least, most teachers and students seem to tacitly agree that audio streams are sufficient. But because teachers now can’t see anything — or have a very limited and grainy view of their students — the content and pace of the class cannot be adjusted based on student expressions or body language.

The pauses I used to leave in my lectures seem abrupt once transferred online, and my attempts to liven the atmosphere with an occasional joke come off as awkward. No matter how hard I try, it’s impossible to break through the wall of silence in front of my screen. Students’ feedback is essentially restricted to “likes” or comments.

Finally, online teaching models tend to infringe on student and teacher autonomy and comfort due to technological surveillance.

Online teaching platforms objectively require more work than their analog counterparts. Such platforms often provide predetermined modules for teachers to fill in, such as “coursework,” “discussion,” and “reference.” Although not specifically required by schools, the design of the platform exerts a silent pressure on teachers to fill these spaces. While this may result in a more disciplined and standardized teaching plan, it comes at the cost of flexibility and autonomy.

Meanwhile, we must record entire classes for students to watch or listen to at their convenience. Data on student playback is naturally also recorded. This information can help teachers understand how and when students are learning, but it also creates a virtual panopticon that is not exactly conducive to feelings of comfort or security. I keep checking myself mid-lecture as I consider who might one day see or hear the thing I am about to say.

Ultimately, livestreaming technology may be better suited to courses that require a lot of writing on the blackboard or laboratory demonstrations. For the humanities, however, I tend to see them as a stopgap measure at best and not something that can replace classroom instruction.

On a conceptual level, the humanities focuses on inquiries into the relationship between the self and the world, society and nature. In place of the experiments found in the natural sciences, or the empirical evidence and fieldwork of the social sciences, it encourages solitary reading and contemplation.

So perhaps we should be looking at other ideas. The current quarantine offers a perfect opportunity for students to free themselves from their usual hectic university lives and engage in quality reading and reflection on the issues raised by the pandemic.

The literature department of Sun Yat-sen University in the southern city of Guangzhou offers an example of what this might look like. Instead of online classes, it recommended a list of over 100 books to students and encouraged them to read and write at home. The idea is, quite frankly, impressive. But it also makes intuitive sense: Reading, thinking, and writing can be carried out independently, so why not allow students to study on their own and hone their independent reading and thinking skills?

Unlike most classes — the lessons of which students may forget as soon as they’re out the classroom door — the impressions they form at this critical time will likely be with them for life. The pandemic offers us a unique opportunity to deepen our understanding of matters like the fragility of human life, the relationship between fate and social systems, and freedom of speech. If the questions posed by literature can sometimes feel abstract or theoretical, experiences such as these bring them home and can effectively shape how we understand and respond to them.

For now, my students and I are eagerly awaiting the end of the pandemic and a return to our beautiful campus: to a world where people can face each other, not perfectly or even efficiently, perhaps, but with emotion and spontaneity.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Zhang Bo and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

(Header image: A teacher’s home-livestreaming setup in Xi’an city, Shaanxi province, Feb. 10, 2020. Li Hui/IC)