I Spent Seven Weeks in a Wuhan ICU. Here’s What I Learned

This article is part of a series of first-person accounts from medical workers who lived and worked in Wuhan over the past four months. The rest of the series can be found here.

It was late at night on Jan. 24, the day after Wuhan went into lockdown, when I boarded a plane bound for the city as part of a 128-member medical support team sent from the southern Guangdong province to the epicenter of China’s COVID-19 epidemic. We received a brief training session the next day, and on Jan. 26, we were taken to the hospital ward where we would spend the next 54 days.

I’ve been a doctor in an intensive care unit for 12 years, and during that time I’ve dealt with all manner of serious diseases. But stepping into that ward was the most terrifying moment of my life.

The cleaning staff and security guards hired by the hospital — most of them contractors — were gone, and the hallways were covered in garbage bags and contaminated medical waste. The ward was staffed by a total of two ophthalmologists and two nurses who were expected to care for 85 critically ill patients in varying degrees of respiratory distress.

Most of these patients should have been in an ICU, not a converted inpatient clinic. That first day, we watched as one of the doctors did their best to save a patient near death. It was no use: The hospital didn’t have enough oxygen left.

Usually, when a patient sees someone in the same room die, they’ll have some kind of reaction. They might ask to change beds, or maybe they’ll turn and cover their head with their blanket. But the other patients in the room just watched, motionless, as the doctor tried to save the patient, as the patient died, as the body was taken away.

It was as if nothing had happened.

State of Emergency

We were stationed at Hankou Hospital, a mid-sized facility and one of the first three hospitals in the city to be converted into a full-time COVID-19 treatment center. The hospital received its first suspected case on Jan. 3, and by the middle of the month it was flooded with patients experiencing sudden chills and fevers. On Jan. 21, three days before our arrival, Hankou was designated a key facility for COVID-19 patients. Overnight, it opened 10 fever clinics. At the peak of the crisis, it received over 1,500 outpatient visits a day — five times the usual number.

When we arrived, there wasn’t an empty bed in the building. Under normal circumstances, admitting more than five patients for observation at a time would be considered unusual. We had more than 80, many of them in serious condition. With no beds to spare, at least one patient died while hooked up to an IV in the emergency room.

The staffing situation was equally bleak. A lack of warning and a severe shortage of personal protective equipment resulted in many frontline respiratory and critical care staff becoming infected. With this group incapacitated, members of the hospital’s internal medicine, gastroenterology, and surgery departments were brought into the fold. By the time we got there, those who hadn’t fallen ill were exhausted from the long hours.

The ophthalmologists were the last line of defense. The remaining doctors and nurses burst into tears when they saw us arrive: If they had gone down, there would have been no one left to step in.

Understandably, this bare-boned staff was too tired to worry about whether the requisite safeguards were fully in place, or whether their workflow and hours were safe, but these problems left them exposed.

When the inpatient ward was turned into an ICU, the quarantine area should have been fully sealed off. Instead, wooden doors were installed between the ward’s sections, allowing patients, doctors, and medical waste to freely commingle. And the area where staff would change into their protective clothing was a dark room only 2 square meters in size. This was extremely dangerous: Protective equipment could be coated in the virus, and putting it on and taking it off in the dark risked accidental contamination.

Back at the hotel that first night, we were in shock. Our team leader said things couldn’t go on like this. The next day, the first thing we did was take steps to prevent cross-infection.

We temporarily sealed the gaps around the doors with adhesive foam strips while waiting for them to be upgraded. We also found someone to install lights and a mirror so staff could see when they removed their protective clothing.

It paid off. When we left over a month later, my team had treated a total of 215 patients, 162 of them critical cases, without having a single member infected.

Strange Symptoms

Arriving in Wuhan, we knew little about COVID-19’s clinical attributes. When we asked some doctors from Shanghai who’d arrived before us, all they said was: “It’s complicated.”

One of the first things we noticed was that our COVID-19 patients had a higher tolerance for hypoxia, a kind of oxygen deprivation, than typical viral pneumonia cases. Patients with other viral pneumonias, such as H1N1, typically develop fevers and feel weak after just 20% of their lungs are affected. But COVID-19 patients could develop severe pneumonia while experiencing only mild respiratory issues. Most patients I treated only had trouble breathing after 60% of their lungs or more were affected.

Thus, the majority of patients displayed relatively mild symptoms in the first week. But this made the second week all the more critical, as patients’ conditions would deteriorate rapidly.

Eventually, hospitals in Wuhan began telling staff that the decision to intubate a patient or not could not be made on the basis of their clinical symptoms. Many doctors came to the conclusion that, by the time a patient is having difficulty breathing, the death rate, even after intubation, is high: The earlier you act, the better.

Doctors outside China have since made similar observations: One doctor in New York City told me that all the patients he had intubated later died.

Bringing the death rate down was our top mission. Faced with so many unknowns, we tried just about everything. I spent my free time poring over the latest scientific literature and talking to my colleagues about what we could do and how we should adjust our treatment plan. We even experimented with drugs like chloroquine, the anti-malarial that U.S. President Donald Trump has hailed as a “game-changer,” though many of our patients experienced severe side effects and couldn’t continue the treatment.

Indeed, in our experience, no medicine was particularly useful. Instead, the most effective solution was oxygen. For around 60% of our patients, oxygen saturation was improved by using oxygen masks with a reservoir bag. In more severe cases, we would also use a nasal cannula and an oxygen mask to increase the volume of oxygen.

Getting hold of it was a headache, however, even as patients needed more breathing assistance. Early on, with oxygen worth its weight in gold, we did our best not to waste it.

Finally, after trying everything we could think of, we located a factory in Wuhan that could supply us with massive 25 kilogram oxygen cylinders. The cylinders proved effective at boosting severely ill patients’ blood oxygen levels, but they were taller than me and highly flammable, making transporting them through the hospital a fraught affair. At the peak of the outbreak, we went through 70 to 80 of them a day.

It felt like fighting a war. The patients couldn’t live without oxygen, so we had to constantly monitor their condition. Hankou Hospital didn’t have ECMO machines to provide life support to critical patients, so our last resort was intubation and a ventilator.

This sometimes required quick thinking. One night, we received a patient in extremely critical condition. His blood oxygen levels had dropped to 20%, and he was in a coma. We immediately intubated him and put him on a ventilator.

Although he woke up and seemed to be recovering, after he depleted his first oxygen cylinder, we had issues attaching a new one. Unable to switch his ventilator back on, the patient’s face started to turn purple: a tell-tale sign of hypoxia in COVID-19 patients. I quickly pulled the tube out of his nose and put it directly into his mouth, which allowed him to start breathing again.

By the time his condition stabilized, it was already 2 a.m. He almost died in front of me.

Close Shaves

Working in a quarantine zone in a hazmat suit is not easy. It’s extremely stuffy in all that protective gear, and the shortage of equipment meant we often couldn’t change or go to the bathroom during our shifts.

The main problem wasn’t poor preparation, but the sudden influx of patients that would have overwhelmed a stockpile even 10 times the size available. Early on, what we had wasn’t high quality. Some suits were very thin, so we wore two or three layers. The resulting get-up was really difficult to take off: We had to undress very slowly, layer by layer, otherwise the thin material would tear. Washing our hands between each layer, it would take 45 minutes to remove it all.

During the worst of it, we relied on each other for support. One young nurse told us that when she felt stressed at home, she would give her pet a haircut to calm down. So the other doctors and nurses started going to her when they themselves needed a haircut. One doctor in Wuhan visited her five times to get his head shaved.

Eventually, the city built 19 fangcang shelter hospitals, most of them to house mild and moderate cases. Combined with an influx of doctors from all over the country, they gradually relieved some of our pressure. And by February, some of the patients were showing signs of improvement.

When we handed the ward back over to local staff on March 19, there were only 20 COVID-19 patients in Hankou Hospital. All of them had tested negative, though they had not yet fully recovered.

Looking Back, and Out

I was cleaning my home when my hospital called for volunteers willing to travel to Wuhan on Lunar New Year’s Eve. I don’t have children and having grown up in Hunan province, just south of Wuhan, I figured I would be more familiar with the region’s relatively cold, damp climate than some of my southern co-workers. As a clinician, I also thought I had a responsibility to learn more about this rare infectious disease.

I never expected to see so much suffering, nor did I envision the outbreak becoming a worldwide pandemic.

At the beginning, former classmates of mine who are doctors in Europe and the United States were all asking me whether we needed supplies or donations. They ultimately contributed a lot of supplies to help us.

By the end of February, however, they were starting to ask about the situation on the front lines. One U.S.-based doctor I know told me that the director of his hospital was encouraging staff not to wear face masks for fear of causing panic among the patients. When he asked me for my opinion, I told him that none of the medical staff I knew who wore protective equipment had become ill. But the director of his hospital failed to take the hint.

Now, my team is back in Guangdong and we have completed our 14 days of quarantine. A lot of us have also started donating face masks and protective clothing to doctors and friends in the U.S.

But ultimately, many things are out of doctors’ control. If there are problems with the epidemic prevention system, and screening isn’t carried out as soon as possible, then medical workers will be left powerless.

As told to Sixth Tone’s Cai Yiwen.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

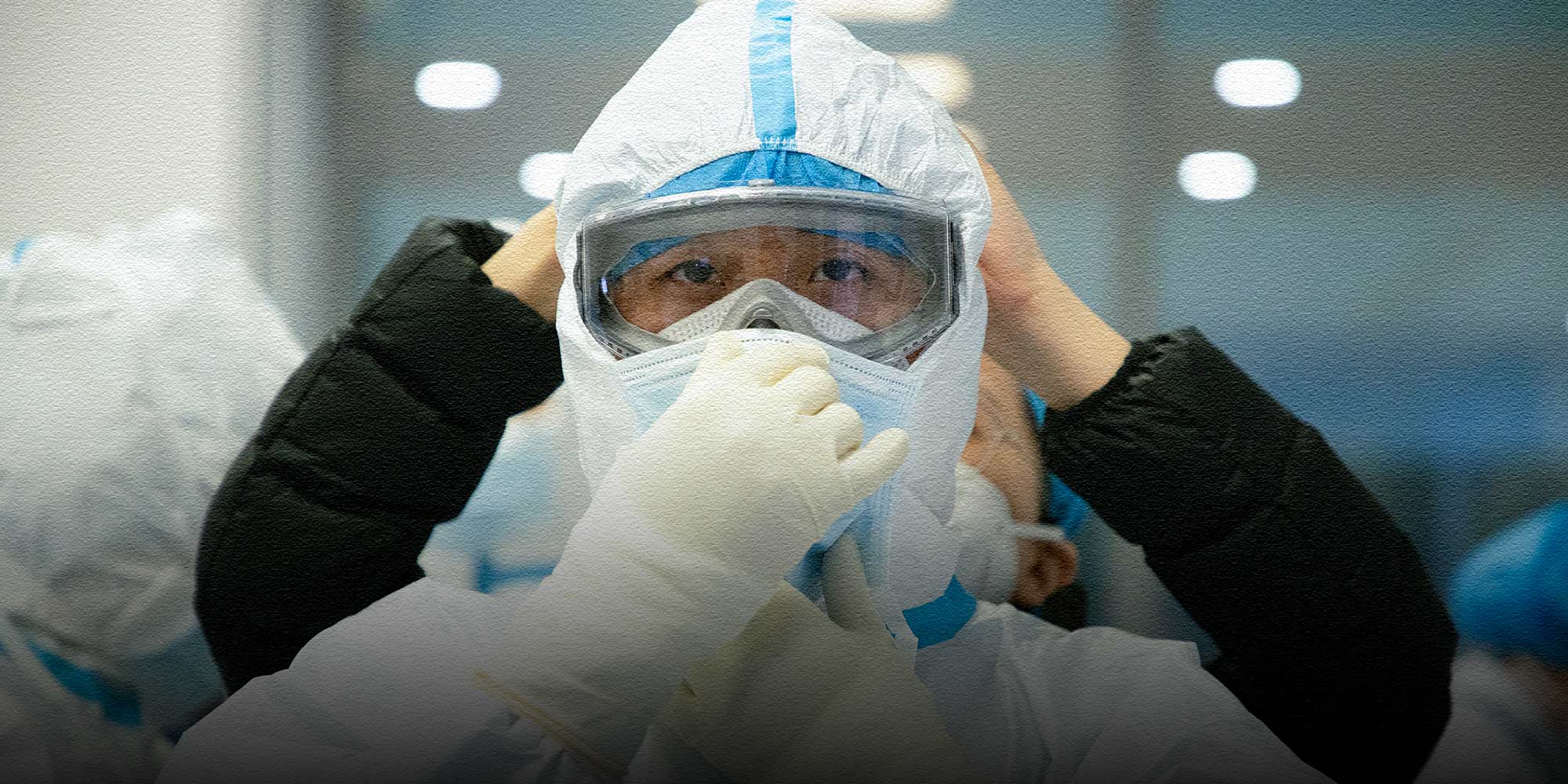

(Header image: A member of a medical worker relief team from Guangdong dons protective gear at a hospital in Wuhan, Hubei province, Feb. 28, 2020. Southern Metropolis Daily/People Visual)