In Wuhan, a COVID-19 Tester’s Search for Answers

This article is part of a series of first-person accounts from medical workers who lived and worked in Wuhan over the past four months. The rest of the series can be found here.

The first time my lab team processed nucleic acid tests given to suspected COVID-19 patients, only 30% of them came back positive.

All of us, physicians and testers alike, were stunned. Most of the individuals tested had clinical symptoms consistent with COVID-19, such as cough, fever, shortness of breath, and low blood oxygen levels, as well as a history of close contact with confirmed patients. Sometimes we gave patients multiple tests, only for their samples to come back negative again and again before they would finally test positive.

We quickly realized the nucleic acid tests we were using at the time, which were tricky to administer and reliant on a newly developed and not yet entirely reliable reagent, were prone to false negatives. As the only officially recognized means of confirming COVID-19 diagnoses, they remained vital, but if we wanted to filter out the noise while we waited for an upgraded version, we needed to look elsewhere.

The seven weeks I spent in the central city of Wuhan helping doctors search for this strange and previously unknown virus were filled with unending bouts of trial and error. Even now, nearly half a year into what has become a global pandemic, there’s much I still don’t know.

Nucleic Waste

I landed in Wuhan on the night of Jan. 24 as part of a medical support team sent from the southern Guangdong province to the epicenter of the country’s COVID-19 outbreak. I did my master’s in virology, a three-year doctorate in laboratory medicine and testing, and have spent the past three years working in a medical laboratory. As such, I was confident I could handle the job. Even before pulmonologist Zhong Nanshan finally publicly acknowledged that the coronavirus could be passed from person-to-person on Jan. 20, I never put much stock in official pronouncements that such transmission wasn’t taking place or that young people were somehow not susceptible to the disease.

Of course, I also didn’t believe the terrible stories trickling out of Wuhan until I got there and saw them for myself.

In the early days of the pandemic, the city’s hospitals and clinics were inundated with thousands of potentially infected residents searching for an explanation for their fevers, coughs, and breathing problems. It was imperative to identify who had COVID-19 and who didn’t — if only to keep the two groups from infecting each other at the hospital.

That would generally be done by administering a nucleic acid test, which can identify the presence of the coronavirus in patients’ respiratory tracts. Later, China would also allow doctors to diagnose COVID-19 on the basis of a positive antibody test result, if given in conjunction with a nucleic acid test. Antibody tests check for unique proteins produced by the body to fight off the virus and are generally faster and easier to process than nucleic acid tests. But it takes time for the body to make antibodies, so the tests are less reliable in the initial stages of the disease’s progression in patients.

In late January, however, we were still a month away from the first government-approved antibody tests hitting the market. Reliable nucleic acid tests were usually in short supply, and some inpatients who were given an early version tested negative three or four times before testing positive.

You could improve the accuracy of the nucleic acid test by getting a sample from deep inside the patient’s respiratory tract, where the virus tends to cluster, but this was highly uncomfortable for the patient, and they would often start hacking and wheezing all over the person conducting the test. Even being covered from head-to-toe in protective equipment wasn’t enough to ease some of my colleagues’ fears about being splashed with potentially infectious spittle.

On Feb. 3, Zhang Xiaochun, a medical imaging expert at Wuhan’s Zhongnan Hospital, became the first physician to publicly propose supplementing nucleic acid tests with CT scans of patients’ lungs.

Unlike nucleic acid tests, CT scans are simple to perform and return results quickly. On Feb. 4, one day after Zhang’s proposal, China’s National Health Commission allowed doctors in Wuhan and elsewhere in Hubei province to make clinical diagnoses of COVID-19 based on CT scans. A week later, the province added almost 15,000 cases to its tally.

But CT scans posed the opposite problem: too many false positives. Influenza, for example, can be difficult to differentiate from COVID-19 on lung scans, but treating influenza patients alongside COVID-19 patients risked cross-infection.

The health authorities eventually halted the practice of using CT scans to confirm cases. Early on, however, our primary goal was simply arresting COVID-19’s spread in the city. Many doctors were willing to overlook CT scans’ deficiencies as a diagnostic tool out of a belief that it was better to misdiagnose influenza as COVID-19 than risk missing a case of the latter.

Still, nucleic acid tests remained the primary way my hospital officially diagnosed COVID-19 patients until antibody tests became available in late February.

Capped Out

Before I went to Wuhan, I heard that manufacturers were already at work producing the components needed for nucleic acid test kits, so I assumed there would be an adequate supply. I soon found that production was unable to keep up with the rising numbers of patients, and logistics networks, jammed by nationwide lockdowns, were struggling to deliver the tests where they were needed.

On Jan. 25, the day after I arrived, Wuhan’s health commission authorized 13 labs to process nucleic acid tests. This should have increased overall capacity from 300 to 2,000 tests per day.

Yet there were more than five times as many patients in need of testing. At the time, our hospital’s quota for nucleic acid testing was just 20 tests per day. We had more than 80 patients in our inpatient ward, not to mention hundreds of visitors to our outpatient clinic every day.

Although our testing cap gradually increased to more than 70 before eventually being lifted entirely, that still didn’t solve our problems: Because our hospital’s laboratory didn’t meet the necessary standards to process the tests, the samples had to be sent out to a third party. On average, it took around five days to get the results back.

Given how quickly COVID-19 patients’ symptoms can change, this delay complicated physicians’ efforts to monitor and diagnose patients. It also limited treatment capacity: Beds were scarce, and delays in processing made it hard to free up resources in time for those in need.

Searching for the Unknown

Facing a disease with so many unknowns, my team worked nonstop to detect the virus as accurately as possible, and we never stopped experimenting.

Antibody testing, which came into use in late February, helped exclude the false positives created by using CT scans as a diagnostic tool. And because antibody tests were less demanding, we could process them at the hospital ourselves, without needing to send them to a third-party lab. If either a nucleic acid or antibody test came back positive, then we could officially confirm a case.

But like everything else we used, antibody tests posed unique challenges. Reliability varied from brand to brand, and the kits didn’t come with clear instructions, increasing the margin of error. For example, a test kit’s sensitivity and accuracy differed depending on whether you tested a patient’s blood serum or blood plasma.

In order to increase the accuracy of our results, we compared new kits as they became available, all while experimenting with different testing methods. In one two-week period, we carried out over 2,000 antibody tests while changing brands five times.

Because our patients all had different constitutions, underlying illnesses, and infections, their antibody counts also varied. For example, some patients naturally produce very few antibodies, and others might take twice as long to produce the proteins. Faced by a virus we could not fully explain, we were always discussing and debating the significance of “weird” or outlier cases.

Beginning in late February, a small number of patients who had tested negative for COVID-19 twice and been discharged from the hospital later tested positive for the virus. This attracted a lot of public concern, especially as similar cases had been reported elsewhere, including in South Korea.

I personally came across two such cases, both of which involved either antibody production that was very low or very slow. In one of them, the patient had initially been hospitalized for a high fever and diagnosed with COVID-19. They were eventually discharged after testing negative twice, as per the guidelines. More than half a month later, the man again developed a fever and returned to the hospital, where he was given another nucleic acid test. This time it came back positive.

Later, we found he was producing relatively low quantities of antibodies compared with other patients, potentially leaving him vulnerable to reinfection. These were isolated incidents, and the risk of reinfection remains unclear. We are, however, continuing to monitor the situation.

There are still a lot of unanswered questions about COVID-19. In particular, the effectiveness and longevity of antibodies — which could conceivably offer resistance to future infections — are among the most pressing concerns. By the end of my time in Wuhan, doctors and testers were relying on a combination of CT scans, antibody tests, and nucleic acid tests to identify and confirm COVID-19 infections, but there’s still much we don’t know. It’s possible this fight is far from over.

Removing the Cowl

Laboratory staff worked every day. During our shifts — which lasted eight hours, if you count all the time spent putting on and taking off protective gear — we were unable to eat or go to the bathroom. Every time I put on my protective suit, I could feel myself tensing up. On the plus side, the work was so stressful, I didn’t have time to feel hungry.

Regardless of my protective gear, I worried about being in close contact with virus samples every day. As a frontline medical worker, some dangers are unavoidable. Then you go home and start to worry about everything that could have happened or whether you’re now infected.

That feeling doesn’t go away overnight. Many of us needed time to adjust after returning home. It was different from a normal business trip, not least because I never expected to stay for two months. I was constantly on edge the whole time I was there. Just like Wuhan itself, getting back to normal may take some time.

As told to Sixth Tone’s Cai Yiwen.

Translator: David Ball; editor: Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

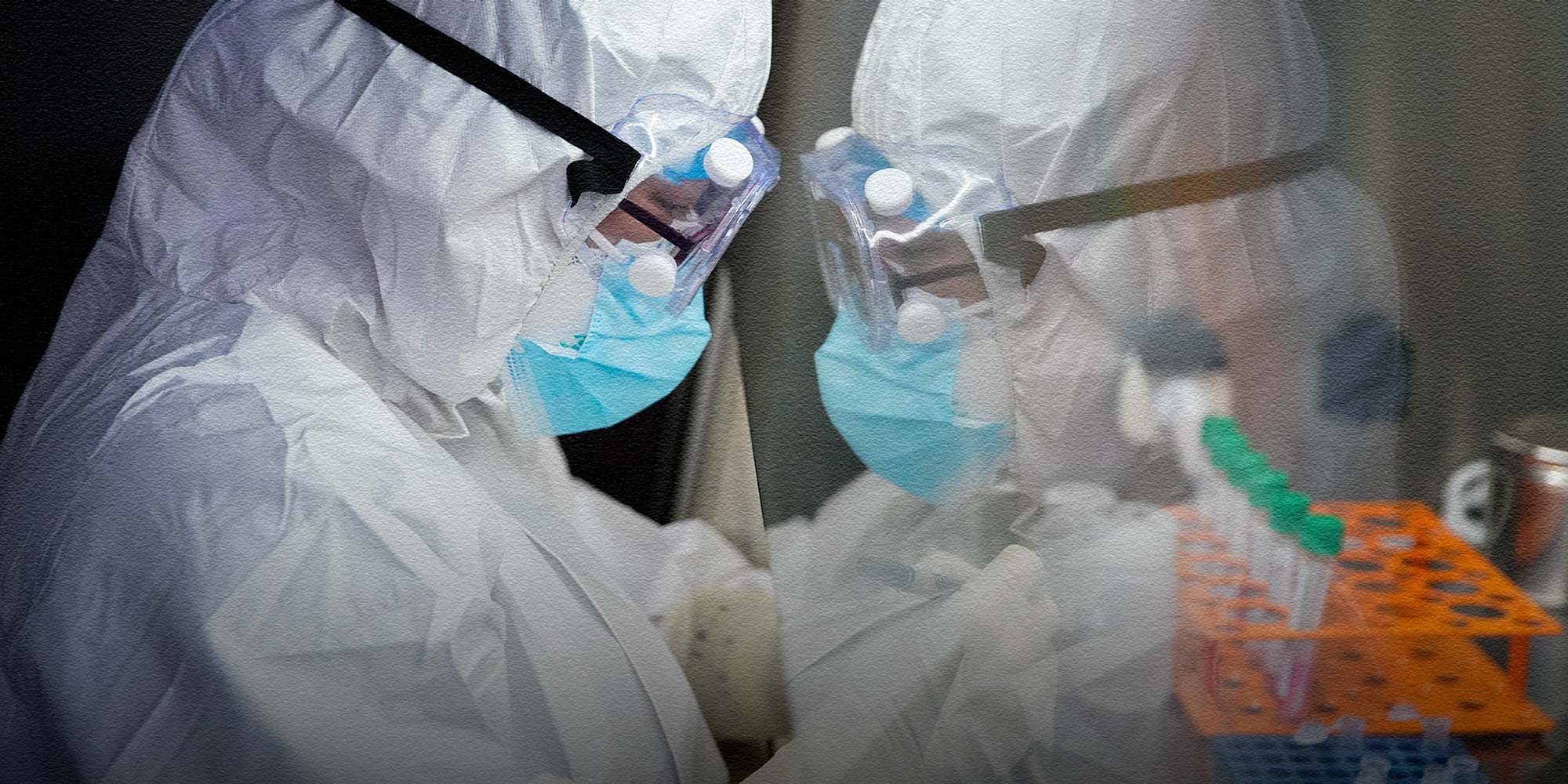

(Header image: A medical worker processes nucleic acid test kits at a hospital in Taiyuan, Shanxi province, March 2, 2020. People Visual)