As Summer Nears, Farmers Struggle to Get Crawfish on the Table

HUBEI, Central China — It’s 3 a.m. and Yao Yong is already up. He puts on his uniform, dons a headlamp, and heads straight to the pond near his village. After measuring the water’s temperature, he gathers his net.

“Crawfish love the water at around 20 degrees (Celsius), and at night, it’s about that temperature,” he says.

Two hours later, Yao and scores of fellow farmers sell their morning catch to the crawfish collectors, who in turn transport the creatures — the “little dragon shrimps,” as they’re called in Chinese — to the processing plants.

Yao owns 40 mu (about 2.6 hectares) of land in Zhishu Village of Qianjiang City, known as China’s “crawfish hometown.” He mainly harvests the crustacean, as well as wheat, corn, and soybeans, which can be used as crawfish feed. While Yao earns about 150,000 yuan ($21,000) every year from farming, at least two-thirds of that comes from the crawfish.

But this year, there isn’t much time left for Yao and the crawfish industry. While in the throes of the country’s COVID-19 epidemic, many regions in the central Hubei province — which produces half the country’s crawfish — ordered strict closure policies to curb the spread of the virus in late January, with sales and produce also suspended.

With Hubei’s annual crawfish catching season starting in late February and lasting until early June, Yao and the province’s crawfish business have a small window of opportunity and are staring at a crisis.

Situated in the northern and middle reaches of the Yangtze River, Hubei, known as the “land of a thousand lakes,” is a province of considerable bodies of water. It is the country’s largest freshwater fish-producing province, and crawfish is the region’s dominant industry to supplement farming incomes.

But the epidemic and its aftermath have caused a “serious backlog of seedlings and processed crawfish,” and the development of the industry is “very grim,” the Hubei Agricultural and Rural Affairs Department said late March.

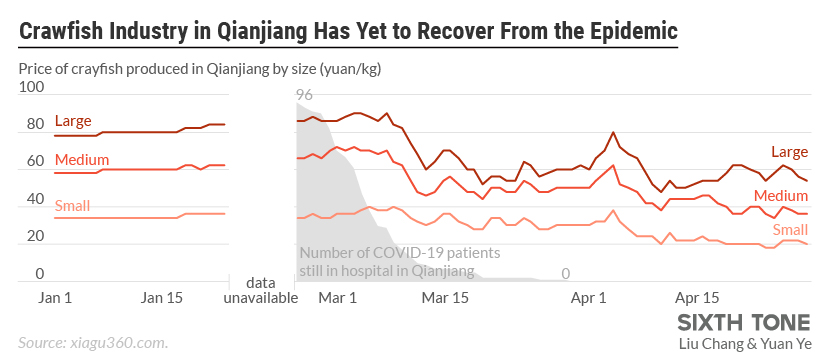

Compared with previous years during the same period, the sales volume of crawfish seedlings and the price they usually fetch have decreased by half, says Gong Dingrong, mayor of Qianjiang. “The logistics channel has not been fully opened, which makes it difficult for crawfish and related products to be quickly delivered to all parts of the country.”

On March 13, the day the lockdown was lifted for Qianjiang City, many of the farmers there rushed to catch and sell crawfish from their ponds. “In the previous months, we couldn’t feed them or clean the water. Their growth has been affected,” Yao tells Sixth Tone. He, however, preferred a more patient approach, saying he would wait until the crawfish grew large enough to sell at a better price.

Yao, 43, quit his job as a physical education teacher and began working on crawfish farms in 2000 for a better income. He soon became a major producer of the crustaceans in the village and was appointed as the village secretary in 2017. Nearly 80% of the village’s 1,000 residents raise crawfish, and half the farmland — about 1,150 mu — is now used as paddy fields for crawfish production.

What worries farmers this season is the price of crawfish, which varies from week to week, day to day, according to Yao. He estimates the overall price to have fallen 40% from last year. When Sixth Tone visits Zhishu Village on April 15, the price has risen by 6 to 8 yuan per kilogram in two days, totaling 58 yuan per kilogram. But during the same period last year, they were sold at over 100 yuan per kilogram.

The price also varies across villages. Zhang Taixin in a nearby town tells Sixth Tone in mid-April that his crawfish sold at 50 yuan per kilogram — the best price he’s gotten all week.

“Last year, we could earn 3,000 yuan from 1 mu of land; this year, we’d be lucky to get 2,000 yuan,” Yao says.

To bolster business, in late March, the province’s finance department implemented supportive policies to local crawfish enterprises, including a preferential guarantee and a one-time financial discount.

In addition, the Hubei Agricultural and Rural Affairs Department has signed strategic cooperation agreements with Chinese e-commerce giants to help the crawfish industry recover.

On April 2, Chinese online retailer JD.com announced a plan to sell 100,000 tons of crawfish sourced from Hubei. Soon after, e-commerce giant Alibaba said it would purchase crawfish worth 1 billion yuan from the Hubei cities of Qianjiang, Jianli, and Honghu from April to August this year, then selling the produce across more than 4,000 stores online and offline to boost thousands of farmers’ incomes.

In April, crawfish were available on the market in large quantities for the first time this year in Qianjiang. The produce has been sold across 402 cities in the country, with Shanghai, Beijing, eastern Hangzhou, and southwestern Chongqing the main markets. Qianjiang’s top officer described in a livestreaming event held on March 21 to promote the delicacy that crawfish produced in the city were “high protein, low fat, environmentally friendly, healthy, springy, and delicious.”

Crawfish, a species not indigenous to the area, are believed to have been introduced into China by the Japanese in the 1930s, and eventually discovered in the Hubei area’s rice paddies in the 1980s. Around 2001, some farmers from Qianjiang began to catch baby crawfish in natural ditches and sell them at markets.

Offline, the number of crayfish stores in 2018 soared by 70% compared with the previous year, according to an industry report. Online, the market share for crawfish takeout also increased significantly. According to delivery app Meituan, the order volume of crawfish deliveries through its platform in 2018 was 2.6 times higher than in 2017.

The popularity of crawfish has also been fueled by the 2018 FIFA World Cup in Russia, during which Alibaba’s food delivery app Ele.me delivered over 3 million crawfish and 400,000 bottles of beer for each game. Meanwhile, 100,000 crawfish were sent to Russia from Hubei during the games, further expanding the popularity of the crustacean.

Due to Chinese people’s love for the so-called little lobster, crawfish chefs with more than three years of experience can earn up to 50,000 yuan a month. Graduates from Qianjiang Crayfish School can make an average monthly salary of over 10,000 yuan, twice as much as others with college degrees in the province.

Over in Gucheng Village, Zhang resumed catching and selling during the second week of April. The 74-year-old has invested 7,000 yuan in this year’s business and so far has earned about 3,000 yuan. “I don’t think I’ll lose money, but the profit will be very small because the price is too low,” he tells Sixth Tone.

The COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent lockdown measures have been a double whammy for the crawfish sector. Fu Wenge, an agricultural economics professor at China Agricultural University, says the price of crawfish has been affected by both the pandemic and an already saturated domestic market. In 2018, the crawfish market in China was worth 369 billion yuan, increasing 37.5% from the previous year, according to an industry report published in 2019.

“There are going to be problems in this industry,” says Fu, who believes supply in the crawfish industry outstrips the demand. “In fact, I think the decline might have some benefits: Hasn’t it developed too fast in the past?”

While farmers say the declining price of crawfish has left them with a smaller profit margin, Fu believes the industry is affected directly by February’s disrupted logistics chain, which is when they’d usually sell the produce. The price of crawfish, on the other hand, has not declined much, losing just 25% to 30% of its value, according to his estimates.

The vulnerable catering industry, already battered by the pandemic, has meant fewer consumers want crawfish. “The demand is now mainly driven by catering, because the biggest part of crawfish sales is in the catering sector. If not for the COVID-19 pandemic, there would be other problems. It (the pandemic) only worsens it,” says Fu.

Compounding the problem is another infectious disease, white spot syndrome, which could cause the crawfish to die come May without proper management. Zhang and other farmers in Qianjiang hope the price of crawfish will increase with the catering sector as the province springs back to life.

But the pandemic’s ripple effects have impacted this industry, too.

Liang Yong, manager of a crawfish restaurant chain in Qianjiang tells Sixth Tone their business hasn’t made a profit this year. Since their restaurants reopened April 1, sales have increased, but it is far from their previous standards. “This time last year, we had 1,000 people eating in the restaurant every day, but now we only see about 400,” she says.

In late March when many restaurants reopened, the volume of food delivery orders in Wuhan, the city at the heart of China’s outbreak, saw a three-fold jump over the previous week, according to Meituan. Crawfish delivery orders skyrocketed 11 times higher than the previous week.

Yet, many Wuhan residents are still cautious about eating takeout, fearing infection. Despite his love for spicy crawfish, Wang Dawei hasn’t tasted any this year. He’s been cooking at home with his wife since the city went into lockdown in mid-January. “We worry that food from outside might contain the virus,” he says. Meanwhile, the small store they own in a shopping mall is losing 1,000 yuan per day, and “ordering a 200 yuan snack seems like a luxury at this moment.”

On the other hand, Liao Fan, another Wuhan resident, ordered over 1,000 yuan in crawfish with hot chiles and piles of garlic as soon as his favorite restaurant resumed takeout services in early April. He puts on disposable plastic gloves to peel the shells while drinking beer with his family of five at home.

“Eating crawfish is the symbol of a Wuhan summer,” Zhang says. “As long as the odor of spicy crawfish permeates the air, we smell hope in the city.”

(Header image: Yao Yong, secretary of Zhishu Village, looks at crawfish in a pond in Qianjiang, Hubei province, April 15, 2020. Shi Yangkun/Sixth Tone)