Subculture Sellouts: Kuaishou and Bilibili Embrace Normcore

This May 4 — Youth Day in China — the popular streaming site Bilibili celebrated by releasing a grandiloquent paean to the country’s young people. Titled “Next Wave,” the ad features He Bing, a well known 52-year-old television actor, delivering a sermon in praise of China’s younger generation: the eponymous “next wave” set to surpass its predecessors. Popular and controversial, it racked up tens of millions of views even while being widely parodied for its overly romantic depiction of life as a young person in China.

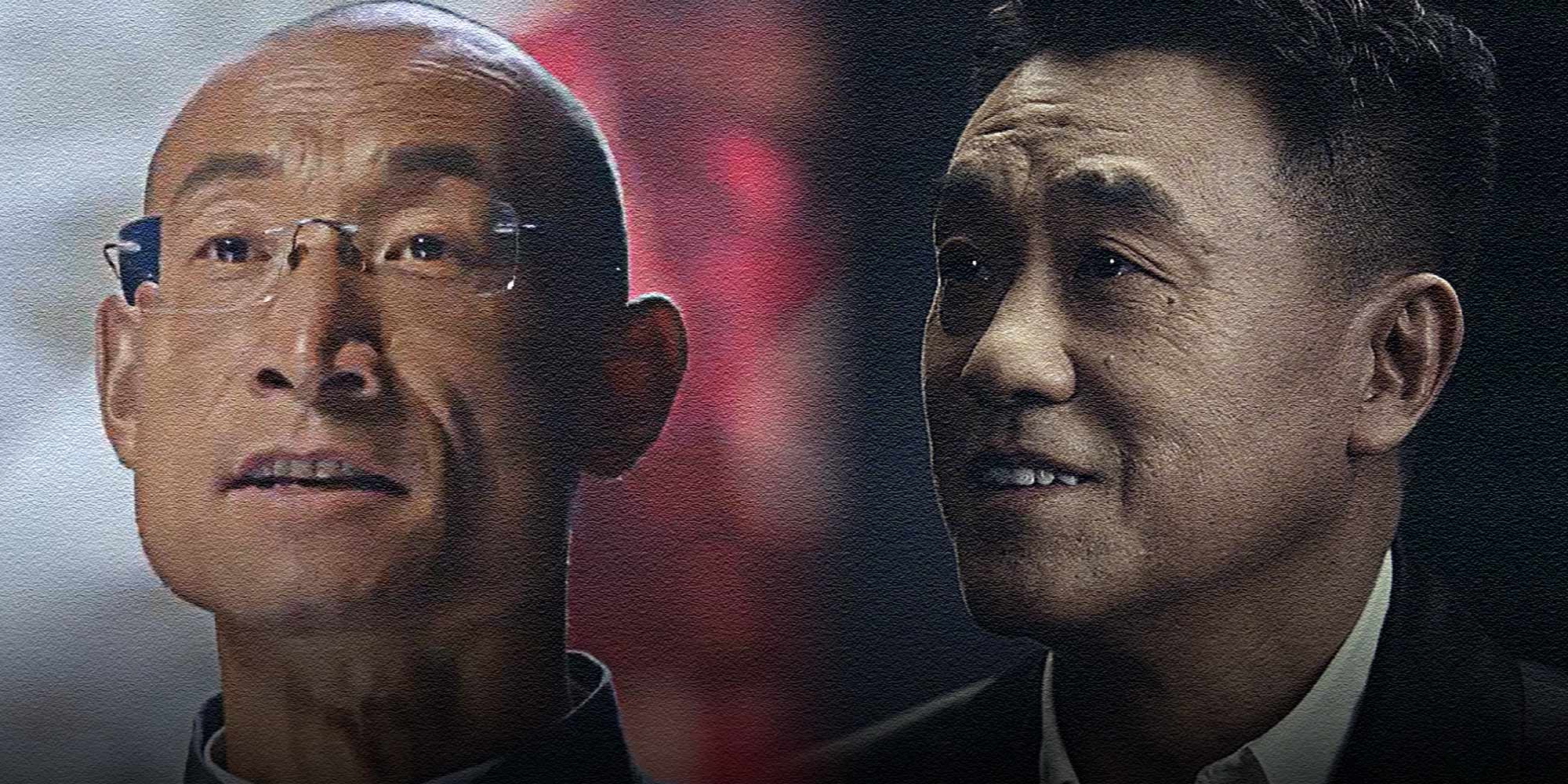

One of the more notable of these parodies came from fellow online video platform Kuaishou. Released earlier this month, “Seen” mimics the impassioned sincerity of “Next Wave” while poking fun at its more overdone elements. Instead of a mainstream TV actor with perfect diction, it features viral video star Huang Chunsheng heatedly, if somewhat stiltedly, beseeching viewers to “broaden their horizons.” Gone are the glossy shots of uniformly attractive young Chinese and their glamorous lives. In their stead are lively clips from the app’s rough-and-tumble users, many of them from the countryside.

For all their stylistic differences, the two ads reflect the apps’ shared ambition: breaking out of their respective niches — Bilibili as a haven for anime, comics, and games (ACG) culture, Kuaishou as an earthier TikTok — and into the commercial mainstream. Of course, as with anything, mainstream acceptance comes at a price.

Take “Next Wave,” for example. Framed as a confession from the older generation, He Bing assumes the role of a tolerant and indulgent father figure willing to defend today’s youth from the grumblings of their elders. He presents a utopian vision of what it means to be young at this moment in time: “The wealth humanity accumulated over thousands of years is spread out before your eyes,” he explains.

As He sees it, the current generation’s greatest advantage is their “right to choose” from all there is to offer. His young audience should be thankful for the right to go on nice vacations and get involved in extreme sports, not bitter about their inability to actually afford them. “It is the weak who are accustomed to satirizing and negating,” he intones. “The strong at heart never stint on praise.”

At a time of extreme economic and social anxiety, Bilibili’s depiction of 2020 as a youthful paradise was ripe for mockery. The parodies typically begin the same way, with a middle-aged man emerging from the shadows into a column of light, but the speech he delivers and the images that accompany it are drastically different from those in “Next Wave.” Some mock inhumane “996” working schedules; others replace the underlying metaphor with a different kind of renewable resource: “chives.” Originally used in reference to hapless individual investors who repeatedly lost their shirts to sharks betting on the stock market, “chives” has emerged as a grassroots in-joke among the country’s economically and socially vulnerable, a self-deprecating shorthand for the way they sprout up quickly, only to be repeatedly harvested by those higher up on the food chain.

On the surface, Kuaishou seems to take a more self-aware tack. By choosing Huang, a self-made middle-aged internet celebrity best known for his relentless positivity and encouraging aoli gei! catchphrase, it strikes a notably different tone from establishment avatar He.

In “Seen,” intergenerational issues are set aside in favor of a focus on the lower rungs and the margins of society, as befits Kuaishou’s primary user base. The advertisement interprets “margins” both figuratively and literally, drawing on clips shot from the Ussuri River along the country’s Russian border to the far reaches of the South China Sea. The featured users, too, include many otherwise disenfranchised by modern society: the disabled, the left-behind rural elderly, the farmers. Huang encourages the audience to take a look at these places and crowds that, like him, don’t fit within the rigid mold of Bilibili’s expensive, cosmopolitan utopia.

Yet just as “Next Wave” is narrated from the vantage point of the previous wave; “Seen” praises the marginalized from the perspective of the urban yuppie. Huang Chunsheng invites young urbanites to pick up their phones, download Kuaishou, and see for themselves how even “ordinary” people can live extraordinary lives. In a jumbled two minutes, the ad attempts to change public perceptions of Kuaishou as a source of crass entertainment for country bumpkins by making a flurry of high-brow allusions, from Bertrand Russell and Dylan Thomas to Socrates.

Even as it parodies the inauthenticity of “Next Wave,” the commercial motivations that underpin “Seen” ultimately mean it can’t help but fall into the same trap. Thus, two seemingly different perspectives merge into one target: young urban consumers.

Back when Bilibili went public in 2018, it was hailed by some investors as a potential Chinese YouTube. If it’s ever going to fulfill that promise, first it has to shed its reputation as an ACG hobby site and convince the public it can balance different youth subcultures with mainstream ideals. “Next Wave” is part of that plan, but there’s a trade-off: Mainstream “positive energy” discourse is not only seen as cringeworthy by many of the content creators who made the site what it is, it — as “Next Wave” itself proves — often fails to accurately reflect the diverse realities of young Chinese people today.

Kuaishou’s appeal to urban youths likewise reflects its desire to make the leap from margin to mainstream. Last June, Kuaishou’s two founders wrote an internal letter in which they called for the abandonment of the company’s “slow and steady” growth model and announced an objective of 300 million daily active users by the 2020 Lunar New Year — an apparent bid to catch up with TikTok’s Chinese analogue, Douyin.

Interestingly, neither of the ads contain any appeal to content creators — theoretically the lifeblood of any platform. Instead, all young people are encouraged to do is click, watch, identify with the values the platform preaches, rinse, and repeat. This is particularly striking in Kuaishou’s case. Since 2018, Kuaishou has replaced some of its most popular — and edgy — stars with sanitized influencers who hawk merchandise on livestreams. Although it remains happy to use its marginalized content creators as props to prove its authenticity, nowadays the conversation surrounding Kuaishou and rival Douyin isn’t about who has the best videos, but which of the two apps is better positioned to monetize the country’s booming livestreaming e-commerce sector.

Watching “Next Wave” on my computer, I was struck by this disconnect. The video had already attracted thousands of “bullet screens” — user comments posted directly over the video itself. Some expressed the poster’s optimistic wishes for a better life, others pride at the development of the country, and a few complained about the state of society. As they rushed across the screen in their own little waves, I couldn’t help but think they offered heartfelt testimony to the very diversity of experience that Bilibili and Kuaishou seem so inclined to whitewash.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: Screenshots of Huang Chunsheng (left) and He Bing. From Weibo)