The Lasting Pain of China’s Identity Theft Victims

ZHEJIANG, East China — On July 3, Gou Jing finally found what she’d been seeking for nearly two decades: closure.

Her entire adult life, the 41-year-old had suspected someone else was living the life she should have led. Now, she knows that wasn’t paranoia. When she was in high school, someone did steal her future — a woman named Qiu Xiaohui.

In 1997, Gou was the victim of an elaborate hoax, which resulted in Qiu taking her exam results, her name, and her place at a vocational school in Beijing. Gou was misled into thinking she’d flunked her exams and had to repeat her senior year, plunging her family further into poverty.

For a long time, such deceptions were a silent, but persistent phenomenon in parts of China. Powerful families used their connections to game the gaokao — China’s college-entrance exams — allowing their children to steal the scores of brighter, but less privileged children.

But over recent weeks, a reckoning has begun over these long-ignored historical injustices. In June, an investigation uncovered hundreds of cases of stolen gaokao scores that took place in just one region — the eastern province of Shandong — between 1999 and 2006.

The revelations generated an enormous public reaction, which convinced Gou — who grew up in Shandong — that now was the right time to come forward and seek justice. Though she wasn’t among the 242 victims identified up to that point, she felt confident a further investigation would prove her right.

“Consider me number 243,” she tells Sixth Tone.

A social media storm managed to win Gou the public inquiry she craved. On June 22, she took to China’s Twitter-like Weibo and posted a list of her allegations. The account was deliberately emotive, designed to create the maximum possible impact. Most eye-catchingly of all, she said she believed her gaokao results may have been stolen twice — in both 1997 and 1998.

“I was looking to attract the attention of the authorities, hoping they could provide me with answers to what had happened,” says Gou.

The tactic worked. Within days, the hashtag “Gou Jing” was trending on Weibo, receiving over 500 million views and tens of thousands of comments. The Shandong government agreed to investigate, publishing its findings just over a week later.

The report’s release, however, has been bittersweet for Gou. Though she at last knows the truth about her past, it’s come at a heavy price. Public sentiment has been mainly supportive, but there’s also been a nasty backlash.

Netizens have accused Gou, who today runs an e-commerce firm selling children’s clothing in the eastern Zhejiang province, of exaggerating the impact the theft has had on her life. Others say she simply went public as a way to promote her company.

When Sixth Tone meets Gou July 6, she has been holed up in her company’s warehouse in the city of Huzhou — a one-hour drive north of the firm’s headquarters in Hangzhou, Zhejiang’s provincial capital — for two weeks, trying to keep her head down. The building is dark and deserted, with piles of clothes scattered across the floor.

“The truth has cost me a calm life and a stable business,” Gou says. “I don’t regret making my voice heard, though.”

The accusations clearly rankle Gou. She stresses she never intended to use the scandal to promote her business: “I don’t need to.”

And although she understands she’s not the “perfect victim” some netizens expect, she’s baffled at the idea that the crime committed against her somehow didn’t matter. From her perspective, the theft damaged her prospects for years afterward and caused her lasting pain.

Growing up in rural Shandong, Gou was a dedicated student. She knew doing well in the gaokao and getting a college education could transform the fortunes of her family, who made their living harvesting corn and rice.

“For kids from the countryside, the gaokao is the only path to change our fates and those of our parents,” Gou says.

Gou studied hard for the gaokao and says she consistently scored well in her mock tests. As the exams approached, she recalls feeling confident.

“I had no plan for the future, but there was one clear thing on my mind: to score highly in the gaokao,” she says. “The higher you score, the more choices you’ll have.”

But when it came time for the results, Gou’s teacher — Qiu Yinlin, also the father of the imposter Qiu Xiaohui — took her aside. To Gou’s horror, he informed her she’d done terribly, failing to get a score high enough to be admitted to any decent colleges.

Qiu Yinlin told Gou her best option was to repeat her senior year and retake the gaokao in 1998. Gou remembers feeling crushed, but accepted her teacher’s advice. She never even submitted her college application form.

“I never imagined anything unfair or even illegal could happen in such a sacred exam,” says Gou.

The extra year of tuition was a huge burden on Gou’s family. Her parents had invested much of their faith and money into Gou succeeding: Of their three daughters, they’d only been able to afford to send two to high school. For Gou to retake her exams, they were forced to borrow money from relatives.

“It wasn’t an easy decision for me and my family,” Gou says. “But if we’d simply given up, I’d have felt guilty.”

Gou sat the gaokao again in 1998, and this time she succeeded in gaining admission to a vocational school in the central Hubei province. After completing her diploma in just over a year, she moved to Zhejiang to look for work.

Without connections or a decent diploma, Gou was forced to take door-to-door sales jobs hawking shampoo and pay phones to make ends meet. But she couldn’t bear to return to her home region after what had happened to her, she says.

“I didn’t want to go back to Shandong,” says Gou. “It was a place of shame I wished to escape.”

It wasn’t until 2002 that Gou realized her failure in the gaokao might not have been her fault after all. Out of the blue, she received a letter from her old teacher, Qiu Yinlin.

The letter was a confession. Qiu Yinlin revealed he’d used Gou’s gaokao score to help his daughter — Qiu Xiaohui — get into vocational school, begging her forgiveness.

At the time, Gou decided against reporting Qiu Yinlin to the authorities. She’d just given birth a few months before and wasn’t in a position to get entangled in the issue, she tells Sixth Tone. For the next few years, she concentrated on her family and career, setting up a store on Taobao — an online retail website that was just beginning to take off — in 2006.

Then, a decade later, Gou discovered something that shocked her even more. At a high school reunion, a former classmate told her Qiu Xiaohui had not only gone to the Beijing school using Gou’s grades: She’d also been living and working under the name Gou Jing.

Stealing her identity couldn’t have been the result of simple opportunism: It would have required advance planning and a wider network of contacts to tamper with the necessary official documents, Gou realized.

“That was more horrifying to me,” she says. “I couldn’t stop wondering what they had planned before I even sat the gaokao in 1997. It wasn’t just a random plan to take away my score.”

Again, however, Gou hesitated about going to the police, as she didn’t have any hard evidence to back up her claims. But when the reports on historical identity theft went viral in June, she finally sensed an opportunity to secure justice.

The investigation largely confirmed what Gou had suspected for years. In 1997, Gou scored 551 out of 900 in her exams — high enough to attend vocational school. But as she never submitted her application form detailing which schools she wished to attend, her spot was left open.

Instead, Qiu Xiaohui attended the school in Beijing under Gou’s name, despite not having taken the gaokao in 1997. After graduating, she also got a job in Shandong using Gou’s identity and continued using her name until 2001.

The fraud was made possible by a network of officials — including employees from local education and public security bureaus — who doctored official records and overlooked discrepancies in Qiu Xiaohui’s paperwork at her father’s request.

Chinese authorities have so far identified 15 people involved in the deception, with most being dismissed from their posts, given warnings, or having their pensions deducted. Qiu Xiaohui has been fired from her job, while investigations into her and her father continue.

According to the report, there was no evidence of foul play related to Gou’s second attempt at the gaokao in 1998.

Gou accepts the authorities’ conclusions, saying she now considers the case closed. She wants to focus on putting her past behind her and getting on with her life, she says.

“From the very beginning till now, what I’ve wanted is not compensation or apologies, but the truth,” she says. “They’ve provided me with the answers.”

Moving on, however, may prove to be easier said than done.

Details about Gou’s company and her clients have been leaked online, leading Gou to close down her Huzhou facility at least temporarily — both to avoid causing her business partners any trouble, and to prove she’s not trying to profit from her newfound fame.

The public discussion about her case continues to simmer. Gou says she understands why her critics have targeted her, but points out her success later in life has given her the power to speak up.

“Many thought I should have ended up begging on the streets or laboring on a farm,” says Gou. “But if I were in such a situation, I couldn’t have made my voice heard to begin with.”

The publicity generated by Gou and the other identity theft victims identified so far has pressured the government to take action. In late June, policymakers began discussing legal revisions that would finally make stealing another person’s gaokao score an act punishable under China’s criminal law.

A central Chinese Communist Party commission has also published a commentary on Gou, underlining that identity theft undermines the very foundations of the gaokao system.

“If even the most basic equity cannot be guaranteed, talking about the fairness of the gaokao from other perspectives is just pie in the sky,” the article states.

Fortunately, reforms to China’s education system since the late 1990s have made it much harder to falsify students’ exam results, according to Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century Education Research Institute, a Beijing-based think tank.

Gaokao scores are now stored digitally in centralized databases, meaning individual teachers and local officials no longer have the ability to tamper with them. “It was impossible (for students) to verify what they scored before,” says Xiong.

Even now, Gou says she still wonders what her life might have been like had she been able to attend the school in the Chinese capital all those years ago.

“As a child from an average farming family, it’s a source of huge pride to receive your education at a school in Beijing,” she says. “I could have had a more stable job. … I could have avoided the jobs that required more physical labor.”

Yet despite everything, Gou still considers the gaokao the fairest way for colleges to select applicants — although she says life has taught her not to judge others by their academic backgrounds.

“When I brought up my daughter, I never let her grades define her,” she says. “I told her there’s a lot she can learn outside the classroom.”

Her daughter, however, has proved to be a stellar student. Last summer, she took the gaokao and — in a moment of poetic justice — won a place at one of China’s top universities.

“Everything that’s taken away from you in life will be returned to you — in one way or another,” says Gou.

Now, Gou hopes to make a return of her own. She’s closed down her Weibo account and says she’ll soon depart her shuttered warehouse, instead heading back to Hangzhou.

“I’m going home and leaving all this behind,” she says. “I need to get back to my life now.”

Contributions: Liu Siqi; editor: Dominic Morgan.

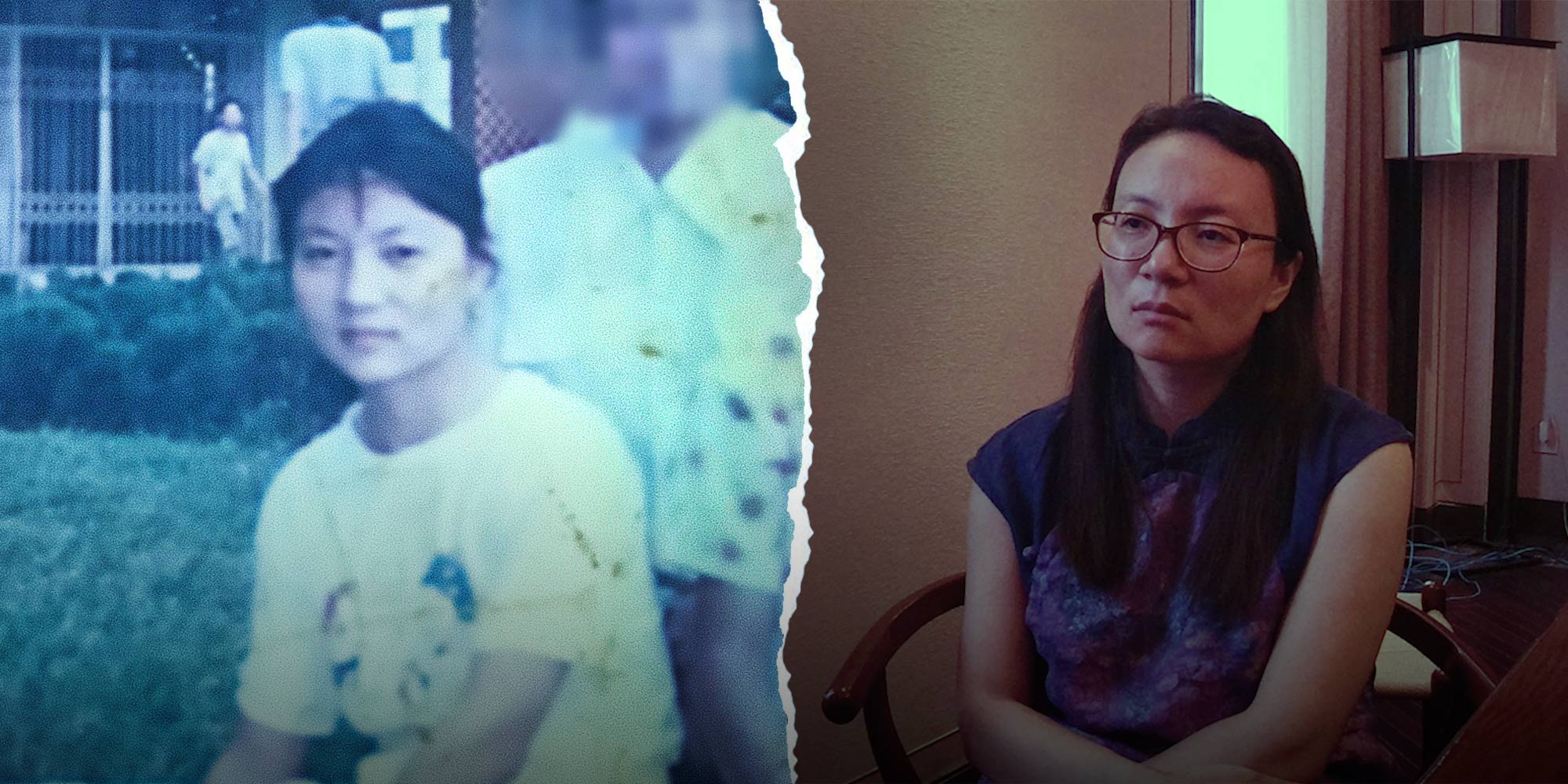

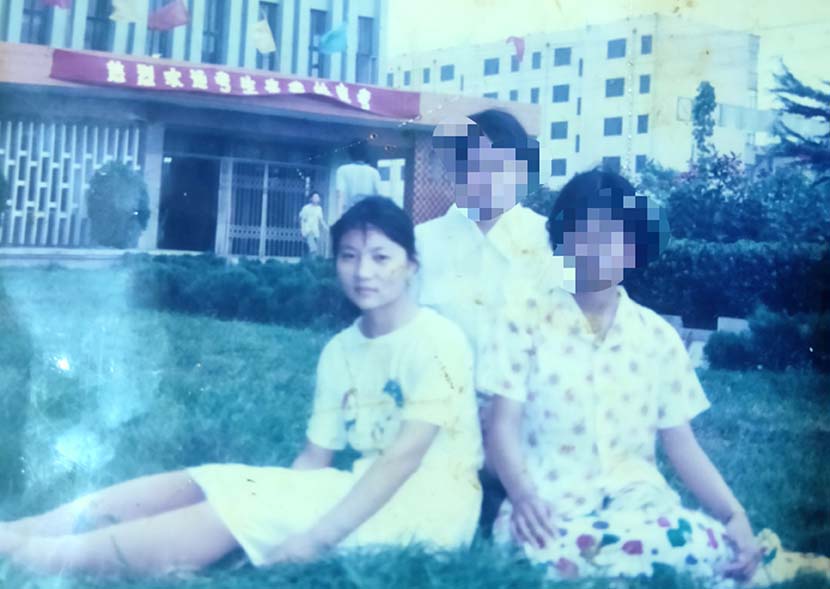

(Header image: Gou Jing during the late 1990s and in 2020. Courtesy of Gou Jing and Liu Siqi)