Tango: The Dangerous Dance of China’s Zany Cartoonist

Pandas aren’t cute in Tango’s cartoons. They’re not good-natured, lazy, or even very tubby. They’re jerks: cunning, rude, and always having the last laugh.

In one of the Chinese artist’s best-known pieces, a polar bear walks into a store owned by a panda to buy a face mask. But the fluffy proprietor simply grabs the bear’s money, takes off a slipper, and slaps it onto the customer’s face as a makeshift face covering.

It’s an irreverent and strangely ambiguous work that has become a trademark for Gao Youjun, or Tango — a cartoonist who can’t help cutting cherished cultural symbols down to size.

“People think Chinese are equal to pandas, but I’m sort of tired of such simple and rough symbolic connections,” the artist tells Sixth Tone. “I like to offer a counterexample.”

Since 2010, the Shanghai-born 54-year-old has been posting cartoons to his social media feeds under his English name Tango — a moniker he chose after watching the Sylvester Stallone movie “Tango and Cash” in college — on an almost daily basis.

According to Gao, he started drawing in the evenings as a hobby, a way to unwind after long days in the office. An advertising executive by trade, Gao says he found creating his anarchic cartoons liberating — a release from the drudgery of continually having to satisfy his clients’ demands.

Undermining famous figures with humor and visual sleights-of-hand quickly became a Tango calling card. In one popular cartoon, fashion mogul Karl Lagerfeld ends up resembling the composer Ludwig van Beethoven after a gust of wind ruins his beautifully coiffed hair; while another features Albert Einstein raising a glass and unwittingly revealing his true identity as a lion.

Netizens loved these playful pieces, which spurred Gao to create more works in what he describes as a “feedback of achievement.” Today, Tango is a bona fide cultural phenomenon in China, with 1.6 million followers on Twitter-like Weibo. He’s also the author of three books and has had his work exhibited in countries including the United States, France, and Belgium.

This July, the comic artist is the subject of a solo exhibition in the southern Chinese city of Sanya, which he says focuses on his relationship with his audience.

“I have anxiety over whether I’ll be able to get across my ideas,” says Gao. “The sense of insecurity — that people might not understand — pushes me forward. I really care about the audience’s feelings.”

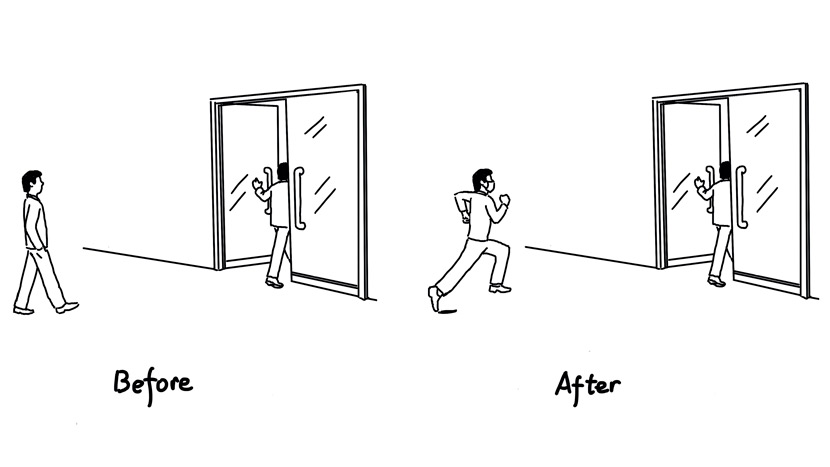

Since the coronavirus pandemic took hold, Gao has tried to bring a smile to his followers’ faces by taking a wry look at how the crisis has transformed people’s behaviors.

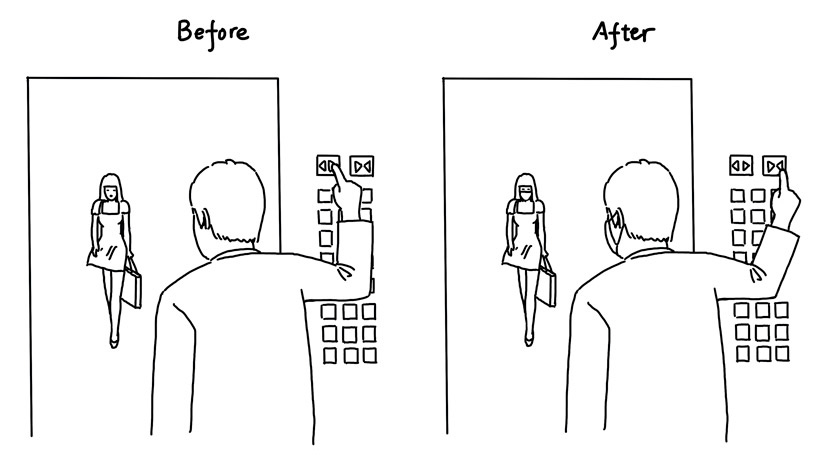

In one widely shared piece, a sketch marked “before” shows a man holding open the elevator doors for an attractive young woman, while a second drawing marked “after” shows the same man — now wearing a mask — pressing the close button, so he can ride the elevator alone.

“I think it’s a kind of ‘light cure,’” says Gao. “Art can’t solve the problem, but it can help reduce the spikes of negative emotions, like a zephyr blowing on your face when you’re in a bad mood.”

Gao’s jokes usually hit the mark, but he’s also had some misfires. The mask-selling panda — a sketch he originally made in 2013, but reposted earlier this year — drew criticism from some quarters.

Overseas Chinese accused Gao of implying that Chinese-made masks were poor quality, while others interpreted the work as playing on the idea that Chinese businesses regularly cheat their foreign buyers. Gao eventually chose to delete the post to prevent further misunderstanding, he says.

“I can accept any open debate or controversy — it’s normal,” he tells Sixth Tone.

In June, Tango also faced accusations of sexism, after creating a drawstring bag featuring a design of a scantily clad woman with her hands tied above her head. Pulling the bag’s string tightens the cartoon woman’s restraints, while opening the bag releases her.

At the time, Gao presented the work as a commentary on the human condition, pointing out that the image was accompanied by an adapted Jean-Jacques Rousseau quote, reading: “humans are born free, but everywhere they are in chains.”

But the post provoked fierce backlash, and two days later Gao posted an apology to Weibo and added a cartoon of his online avatar to the back of the drawstring bag. Now, pulling the string tightens restraints around Tango, too.

The moves, however, failed to satisfy many of his critics. When asked about the controversy, Gao is evasive. “People have different ideas about my work,” he says. “There’s no absolute right or wrong.”

Though success has brought more scrutiny, it does also have its benefits. For one thing, Gao can get more sleep these days, he says.

He used to stay up late every night finishing new cartoons, but nowadays he’s changed his old tagline — “a drawing a day” — to the more laid-back, “a drawing every now and then.”

The change feels appropriate. To the end, Tango refuses to play by the rules — even the ones he invented himself.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

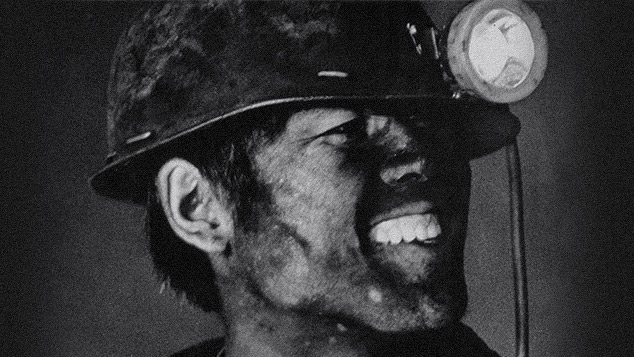

(Header image: A Tango work from 2013. Courtesy of Tango)