The Backstory of China’s Real-Life ‘Farewells’

When I first met Ning in 2016, the 59-year-old cancer patient thought he was receiving treatment for some minor chest pains. Before I was allowed to see him, his daughter warned me not to give him reason to think otherwise: She and the rest of his family still hadn’t told him he had esophageal cancer.

Unaware of how ill he really was, Ning continually complained about his doctor’s examinations. He was worried the treatment was causing him more harm than good. But perhaps he also began to realize something more serious was afoot. I once watched him loudly scold his children — in a voice that betrayed his anxiety — for “never telling him anything.”

Two weeks later, I learned from the hospital administration that Ning had insisted on being discharged and was back home. I never learned what happened to him.

If any of this sounds familiar, that may be because Ning’s plight bears a striking resemblance to the plot of Lulu Wang’s “The Farewell,” in which a New York-raised Chinese American woman clashes with her family over whether or not her grandmother back in China has a right to know she’s been diagnosed with cancer. Her Chinese relatives prefer to hide the truth from the family matriarch and instead organize a wedding as a pretext to bring everyone together for a final goodbye.

When “The Farewell” finally hit Chinese theaters this January, it did so under a name Ning might have found relatable: “Don’t Tell Her.”

Family members hiding cancer diagnoses from a patient is commonplace in China. Many Chinese believe the family unit can and should obtain information and make decisions on a sick person’s behalf. There’s also a widespread belief that concealing information from a sick person about their illness will save them unnecessary anxiety and expedite their recovery. In this, they’re often helped by the patient’s own doctors, who conspire with relatives to keep patients — especially elderly patients — unaware of their true condition, either by telling them white lies or simply not telling them anything at all.

But while cultural factors and strong family structures can partially explain why Chinese may choose to keep sick loved ones in the dark, they do not tell the whole story. For the most part, China’s national health insurance systems provide only limited financial support for major diseases such as cancer, leaving patients and their families to bear the bulk of medical expenses. Since they’re helping foot the bill, family members — sometimes including extended family — tend to feel entitled to make decisions on a patient’s behalf.

Because medical care can require a significant outlay of family resources, the decision to inform a patient of their condition often comes down to whether or not the family unit can afford the patient’s treatment as well as how they have chosen to share cost and care responsibilities. If a family has the capacity to care for and financially support a sick member, they will generally work up the courage to inform them of their condition, and patients themselves will also feel less guilty and more confident about their prospects.

When resources are strained, on the other hand, the financial needs of elderly patients must be weighed against those of younger family members. But topics like how paying for a round of chemo for a parent could impact one’s ability to support a child’s educational pursuits aren’t exactly easy to broach. Heated debates can arise between family members due to differences of opinion, their relationships with the patient, and their own personal interests. The matter is sometimes so contentious that huge family meetings are called in which everyone but the patient is present.

In other words, the nature of our nation’s health care and insurance systems makes illness a family affair. This affects doctors, too: Medical practitioners often consider a family’s financial situation and seek their authorization before informing patients of their diagnosis. Some even adjust treatment plans based on a family’s financial circumstances rather on what has the best chance of success.

In many countries, these practices would be frowned upon, if not outright illegal. Typically, respecting a patient’s autonomy means making sure they are the first person to know of their diagnosis.

China, too, has had legal provisions aimed at guaranteeing patient autonomy, including by getting their informed consent, since the 1980s. But these are poorly enforced and subject to a patchwork of regulations and rules, some of which are ambiguous or seemingly contradictory. There’s no one body capable of providing health care professionals guidance on what to tell patients, when to tell them, and under what circumstances.

Moreover, given the fraught, sometimes violent tensions between Chinese doctors and their patients and patients’ families, medical practitioners have learned to be cautious. In a training session at the tumor hospital where I conducted fieldwork, a senior doctor specifically advised new staff not to tell patients anything “without weighing matters” and seeking permission from family members first.

To make his point, he cited an earlier case in which a doctor was taken to court by the family of a patient who leapt to his death after learning about his condition. Worried about the potential blowback, many doctors prefer to let family members bear the burden of keeping patients informed.

That’s hardly a solution. When patients are kept in the dark for too long, they can become overly optimistic about their situation. This makes it all the more difficult for them to overcome their disappointment and reckon with reality when the truth finally comes out. The breach of trust also causes some to feel isolated or abandoned.

Family members, too, suffer from this state of affairs. I’ve had several family members break down and cry when discussing their loved ones’ conditions with me. Their inability to be open with their sick relatives puts them under immense psychological and financial stress. A few later expressed regret for not informing their parents of the danger they were in. By keeping it secret, they missed a chance for closure.

China needs to look to other nations and regions for solutions in keeping with its own unique cultural and social context. Doctors have a responsibility to inform patients of their condition, but that doesn’t mean they can’t organize meetings with family members and listen to their concerns before doing so. With family members’ help, doctors may develop an idea of what the patient might want, or how best to convey potentially devastating or confusing information. Not only would this alleviate family members’ emotional burdens, it would also encourage better practices when it comes to disclosing diagnoses.

At the end of “The Farewell,” as a taxi takes the Chinese American granddaughter away, she keeps her eyes trained on her grandmother as she fades into the distance, knowing it may be the last time they see one another. When she finally turns back around, she notices that her mother, who insisted on keeping the illness a secret, is crying. Rather than run away from these difficult conversations, Chinese society must learn to face death and disease head-on, together. And that means providing the needed resources and support for patients and their families, before it’s too late to say farewell.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yiwen and Kilian O’Donnell.

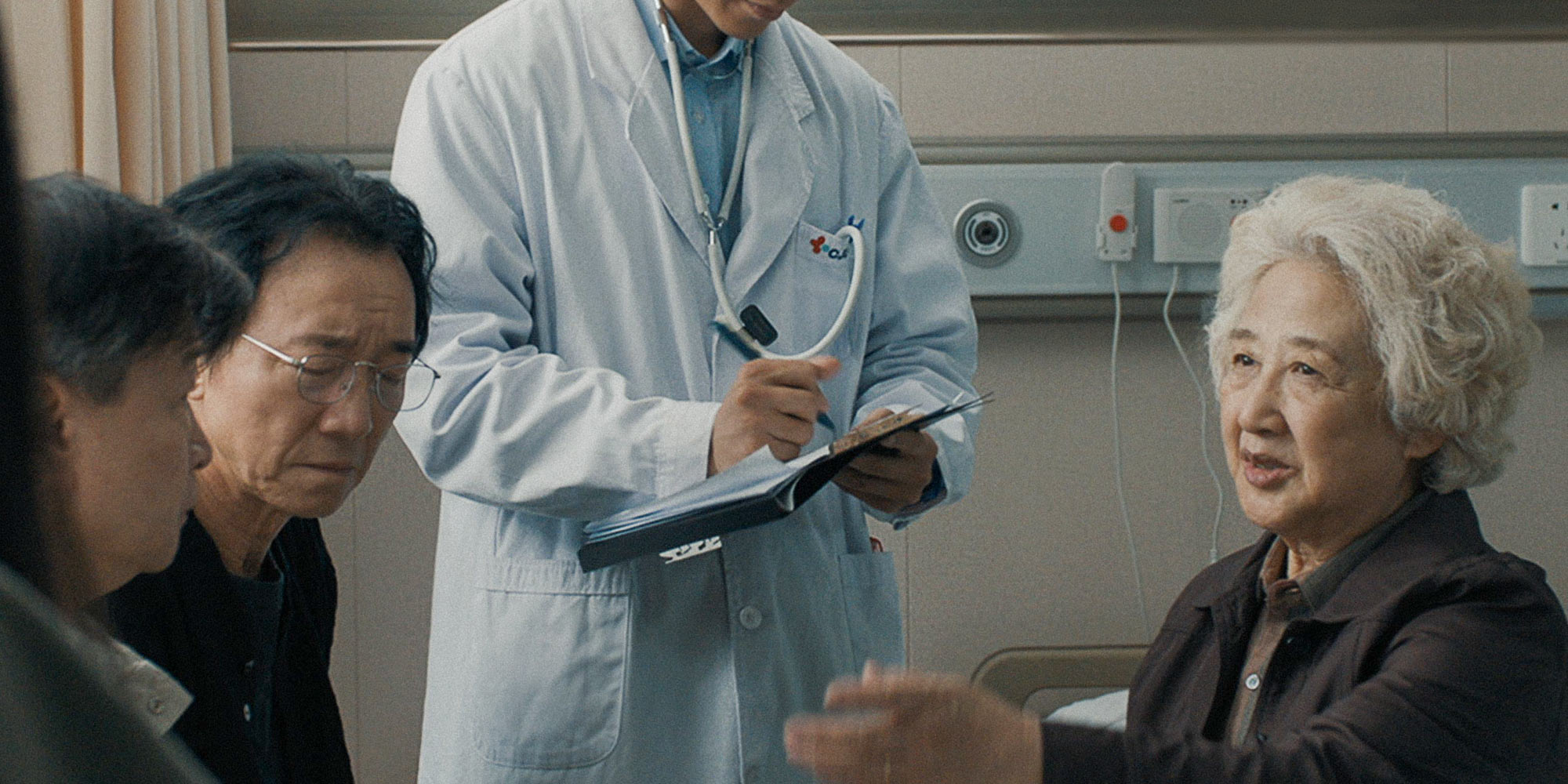

(Header image: A still frame from the 2019 film “The Farewell.” From Douban)