Closed Borders, Open Letters

On Aug. 5, 1954, an open letter from 26 Chinese scholars studying in the United States landed on President Dwight Eisenhower’s desk. It was the height of the Cold War, and the letter’s signatories were lobbying not for the chance to stay, but the right to leave:

In the seeking of knowledge and wisdom, some of the undersigned have had to leave behind their beloved wives and children. In most of the cases the painful separation has already lasted seven years, and their return is still being denied. The plight of others, although not married, is by no means less tragic. Distressed and unsettled, we are forced to let slip through our fingers the best years of our lives.

The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, China’s subsequent entry into the Korean War, and the rise of anti-communist McCarthyism in the U.S. left Chinese students in America standing at a crossroads. They had come to the United States to study at some of the world’s best universities, but after the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War, many in the American government worried their return could give a boost to an ideological foe. Some opted to stay. For the hundreds that didn’t, a September 1951 U.S. government decision to detain 21 of their hopeful returnees in Honolulu kicked off a years long struggle to get home.

It was not the first time Chinese students in the U.S. were treated as a geopolitical bargaining chip — nor would it be the last. Historically, the presence of Chinese students on American campuses has never been a purely educational issue, for either country. But no matter how politicized the atmosphere has become, there have always been some willing to speak up in their defense.

Although there were scattered cases earlier, the Qing dynasty formally began sending students to live and study in the United States in 1872. Their mission was clear: Quickly master Western military, shipping, and manufacturing skills.

Yet many in China worried these young men would be corrupted by the evils of Western culture. In 1881, growing opposition from conservatives in China led the Qing government to order all students home immediately. In response, American educators, including Yale’s then-president, Noah Porter, sent an open letter to the Qing government protesting the move:

The young men have been taken away just at the time when they were about to reap the most important advantages from their previous studies, and to gather in the rich harvest which their painful and laborious industry had been preparing for them to reap. The studies which most of them have pursued hitherto have been disciplinary and preparatory. The studies of which they have been deprived by their removal, would have been the bright flower and the ripened fruit of the roots and stems which have been slowly reared under patient watering and tillage. We have given to them the same knowledge and culture that we give to our own children and citizens.

Porter’s letter went unanswered, and it would be another two decades before Chinese students again stepped foot on American soil. The year was 1905, four years after the U.S. and other world powers extracted a sizable indemnity from China in the wake of the Boxer Rebellion. Joint lobbying by the Chinese Ambassador to the United States Liang Cheng and the American Ambassador to China William Woodville Rockhill eventually convinced the U.S. government to set aside some of the funds to establish a scholarship program to send Chinese students to the United States.

Unlike the previous generation, sent by the Qing government for its own gain, this wave was encouraged more by the host country, which saw the students as a means to change China in potentially useful ways. As Edmund James, president of the University of Illinois and key advocate of the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, put it: “The nation which succeeds in educating the young Chinese of the present generation will be the nation which for a given expenditure of effort will reap the largest possible returns in moral, intellectual, and commercial influence.”

Just as James had hoped, many of these scholars — including philosopher Hu Shi and scientist Zhu Kezhen — did in fact take what they learned home with them. Sometimes ignored, however, is the fact that they had little choice. Thanks to the Chinese Exclusion Act and virulent anti-immigration sentiment, Chinese students were essentially barred from taking up employment in the U.S. after graduation: The immigration cap was set at just 100 immigrants from China per year, compared with 50,000 from Germany.

Nevertheless, many Chinese students built lasting relationships while in the U.S. and even found some willing to take up their cause. On Oct. 20, 1954, Li Hengde — one of the 26 students who signed the letter sent to President Eisenhower and a future top nuclear researcher — finally received clearance to leave. Before departing, he paid a special visit to Ira Gollobin, an American civil rights attorney who had helped him make his case — and suggested the open letter. “Just as I was about to turn and leave, he (Ira) suddenly hugged me tightly and pressed his face against my cheek,” Li later recalled. “This tight embrace from a friend whom I first met in Philadelphia train station just two years earlier, and who had shown us such selfless support, took away the pain of three years spent detained abroad.”

Although there would not be another influx of Chinese international students to the U.S. until after the Mao era, Chinese today make up almost 40% of America’s international student body. Until recently, they were welcomed. The Trump administration, however, has placed a raft of restrictions on international students, including many specifically targeting Chinese scholars and graduate students.

Yet again, the Ira Gollobins and Noah Porters of the world have pushed back. On July 8, 2020, president of Harvard Lawrence Bacow wrote an open letter to the university’s international students, including over 1,000 from China:

For many of our international students, studying in the United States and studying at Harvard is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. These students are our students, and they enrich the learning environment for all … until that time comes, we will not stand by to see our international students’ dreams extinguished by a deeply misguided order. We owe it to them to stand up and to fight — and we will.

A frost has settled over the Sino-U.S. relationship — and possibly over America’s engagement with the world. But Bacow’s letter, like Ira Gollobin’s embrace of Li Hengde during the McCarthy era or Noah Porter’s attempt to convince the Qing government of its mistake, reminds us there is always warmth within.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Zhang Zeqin.

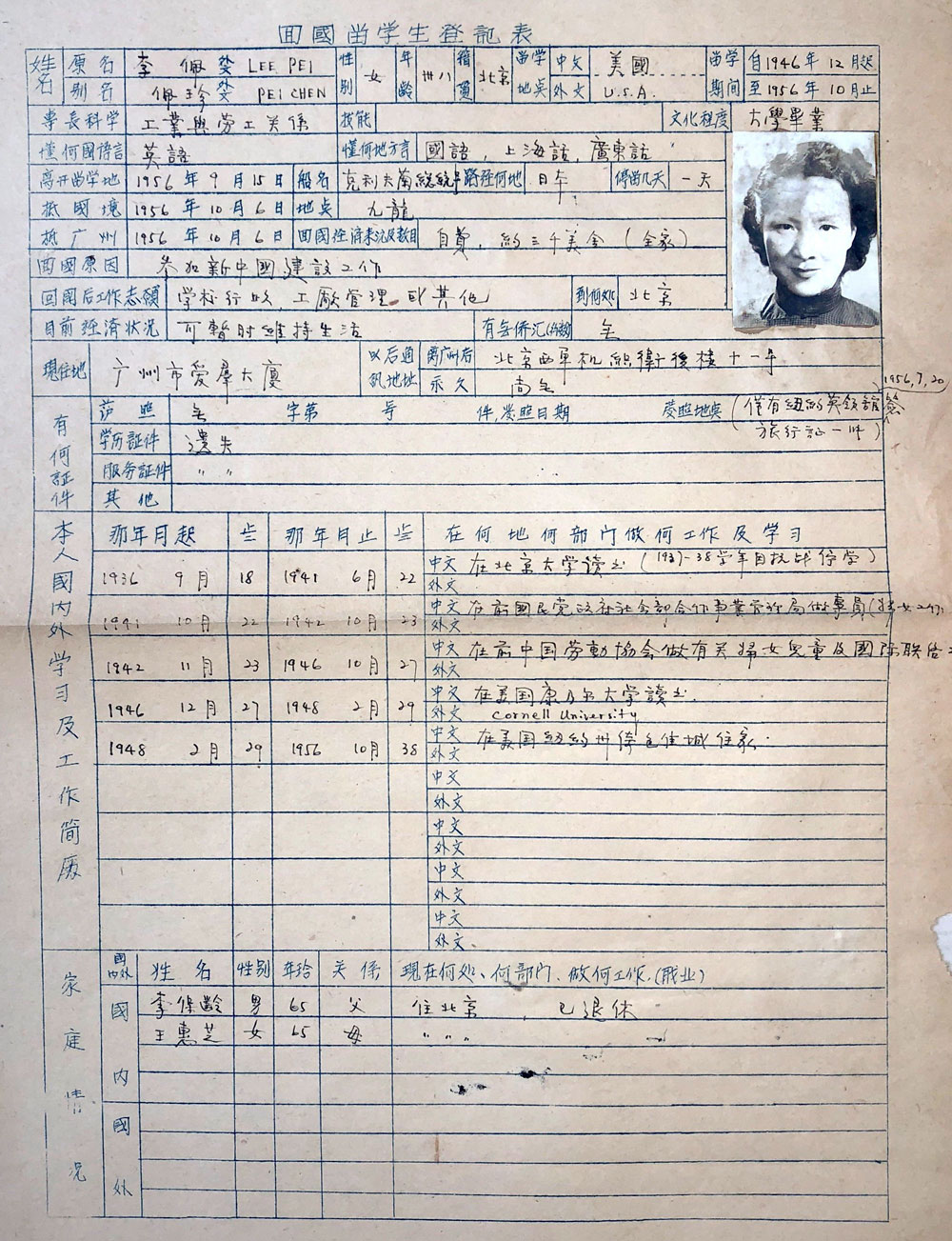

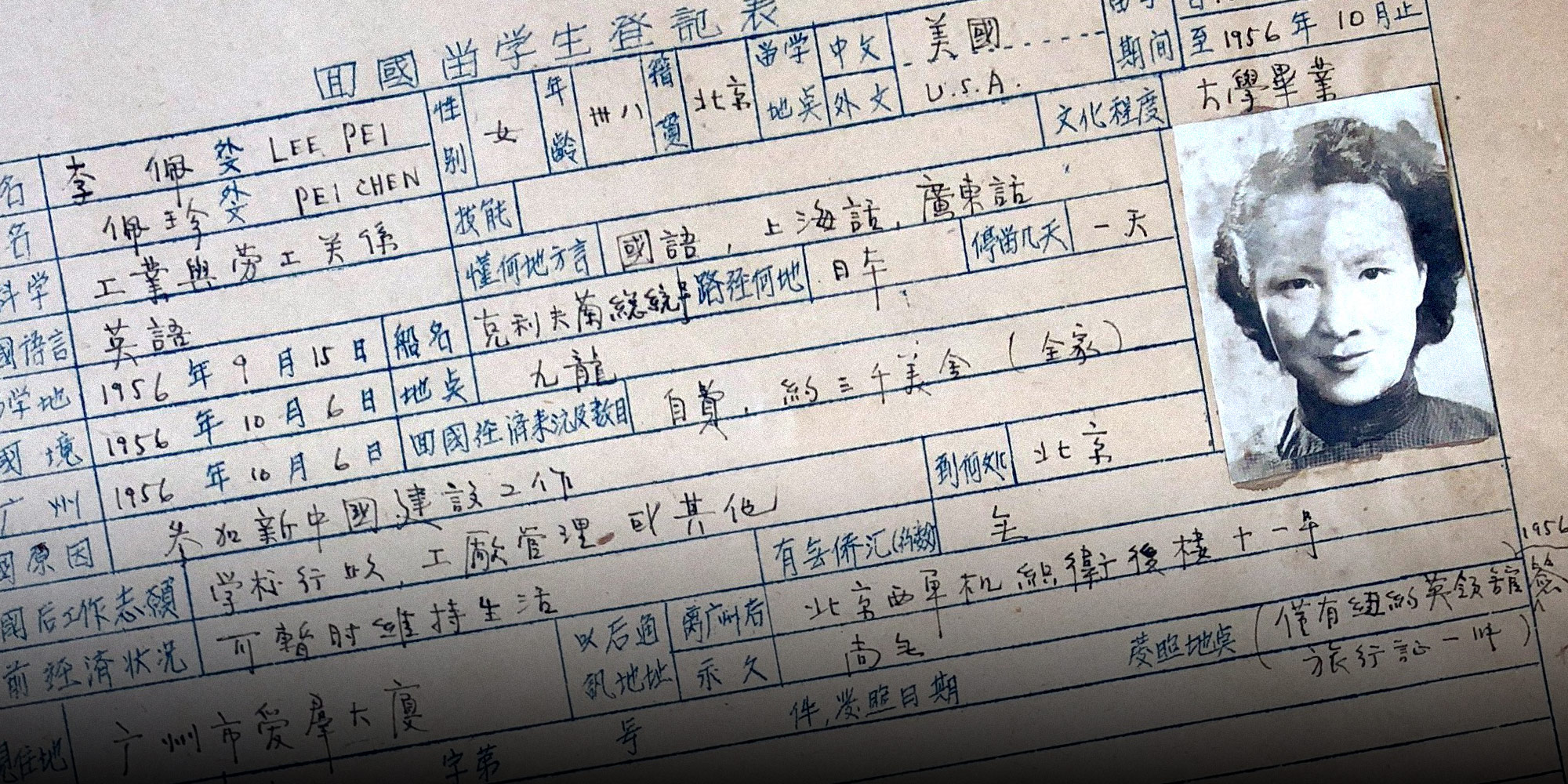

(Header image: Closeup of a registration form filled out by a returning student in 1956. Courtesy of Wu Jingjian)