How Guan Yu Became China’s God of War, Wealth, and Everything Else

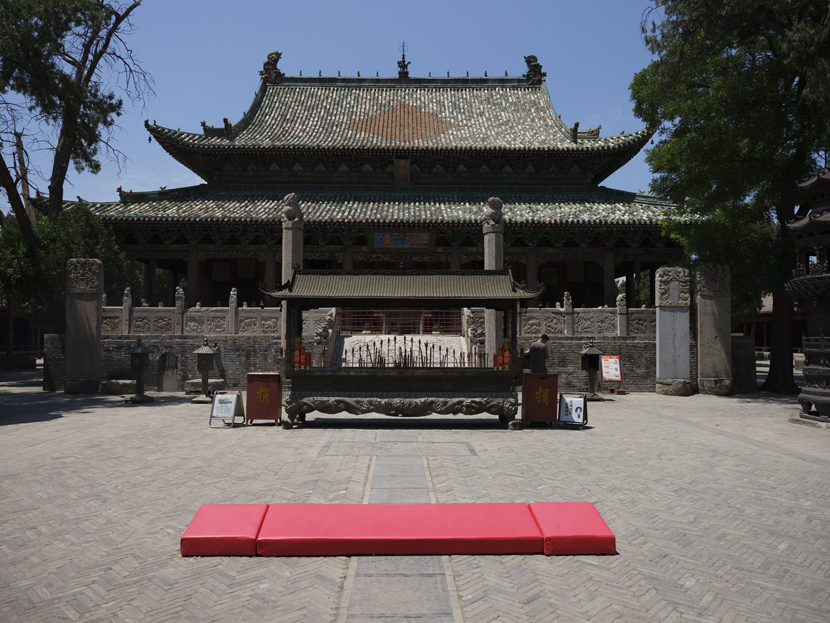

Wei Long’s year has not gone according to plan. Going into 2020, the 57-year-old director of the Haizhou Guandi Temple Conservation Institute in the northern city of Yuncheng had spent the better part of three years and 12 million yuan ($1.72 million) on “God of War Guan Gong.” The animated film was to be a 1,860th birthday present of sorts to his temple’s deity, the famed warrior Guan Yu.

Then COVID-19 hit. The film, which was produced in collaboration with the well-known animator Cai Zhizhong and released Jan. 11 on the Chinese mainland, was quickly lost in the shuffle.

“Following in the footsteps of (animated hits) ‘Monkey King: Hero is Back’ and ‘Ne Zha,’ we were confident the film would be a smash hit,” Wei tells me from his office at the institute’s headquarters in Yuncheng, also Guan Yu’s hometown. “But we can’t complain. After all, we’re working for Lord Guan!”

Positive energy is an asset in this line of work. Since ascending to his current position in 2004, Wei’s spent much of his time traveling between the thousands of temples dedicated to Guan Yu across China and around the world, guiding restoration work, organizing exhibitions, and overseeing temple rites. Yet with the deity’s birthday fast approaching — by tradition, Guan Yu’s birth is celebrated on the 24th day of the sixth month of the Chinese lunar calendar, which this year falls on Aug. 13 — he’s planted himself in Yuncheng to manage the celebrations there.

Few historical personages are as venerated in the Chinese-speaking world as Guan Yu, who counts Guan Laoye (Grandpa Guan), Guan Gong (Duke Guan), and Guan Di (Emperor Guan), among his litany of officially bestowed titles. To those familiar with the history of China’s Three Kingdoms period (220-280 AD), these honors might seem perplexing. Although a competent military general and tenacious fighter, Guan Yu could be coldly arrogant, and he was hardly a master strategist like his comrade Zhuge Liang. Despite his posthumous “Emperor Guan” moniker, he also never staked a claim to royalty, meaning his status in life was never that of contemporaries Cao Cao, Sun Quan, or his liege and sworn brother Liu Bei.

Consequently, Guan Yu’s cult grew only slowly through the Tang dynasty period (618-907), but his status reached new heights during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Emperor Huizong of Song, a bumbling ruler but a devoted Taoist, was the first ruler to make Guan Yu a “deity” in the official Taoist canon. The founder of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) later gave him the higher title of “(heavenly) emperor.”

More honors would follow, and by the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912, Guan Yu’s prestige may have surpassed even that of Confucius himself. Of the country’s three major belief systems — Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism — Confucius has been deified in only one. Guan Yu, on the other hand, is admired by proponents of all three: To Confucians, he’s a “sage,” to Taoists he’s “Holy Ruler Deity Guan,” and to Buddhists he’s the “Sangharama Bodhisattva.”

Just as important, at the grassroots level of society Guan Yu became a kind of patron saint or protector god for everyone from blacksmiths and opera performers to triads and police officers. Nor is his appeal limited to the martial: So many merchants started worshipping Guan Yu, he’s become one of China’s four main wealth gods.

What explains Guan Yu’s almost supernatural popularity, capable of bringing together cops and criminals, emperors and commoners, Taoists and Buddhists? The answer is the one thing Guan Yu was once known for above all else, even his luxurious beard: his sense of zhongyi.

A portmanteau of the Chinese words for “loyalty,” zhong, and “righteousness,” yi, Guan Yu’s steadfast, sometimes bullheaded adherence to the principle of zhongyi proved key to his meteoric rise. China’s emperors, who valued loyalty in their subjects, saw Guan Yu’s obedience and respect for his superiors as a value worth propagating. To ordinary people, meanwhile, it was Guan Yu’s yi that made him a legend worth believing in.

In this case, “righteousness” may not be the best translation of the term, which has complicated connotations in Chinese. Guan Yu was capable of acts of cruelty and extreme violence, but his yi manifested as a strict code of behavior and sense of honor, two necessary components of any good folk hero. If anything, the flawed side of Guan Yu’s yi actually enhanced his popularity with regular people — his imperfections only made him seem more relatable.

A vignette from the famous Ming dynasty novel “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” illustrates the way Guan Yu juggled these two values. Liu Bei’s rival, Cao Cao, captures Guan Yu, but instead of killing him, he spares his life, showers him with gifts, and even procures a court position for him. In return, Guan Yu obediently submits to his new liege and seeks to serve him by performing a great deed.

After repaying his debt by slaying two of Cao Cao’s enemies, however, Guan Yu spurns the additional gifts offered by the despot and returns, honor intact, to serve at the side of his beleaguered sworn brother Liu Bei. Some years later things come full circle: A victorious Guan Yu has the chance to kill a fleeing Cao Cao, but lets him go out of respect for Cao Cao’s previous generosity — even though doing so could have cost Guan Yu his head.

During the Qing dynasty, the country’s ethnic Manchu rulers heaped praise upon Guan Yu for being willing to set aside his loyalty to Liu Bei and pragmatically bend the knee to Cao Cao when circumstances called for it. His adherents among the masses, on the other hand, accepted his increased prominence as the just dividends of righteous conduct.

Balancing both zhong and yi is no easy feat. Outside of Guan Yu, the best known avatars of yi are probably the heroes of “Water Margin,” a classic novel equal in status to “Romance of the Three Kingdoms.” Yet the protagonist of “Water Margin,” the bandit leader Song Jiang, eventually sacrifices his code of brotherhood and leads his band to disaster to prove his loyalty and earn a pardon from the imperial court. In the end for Song, unlike Guan Yu, zhong won out.

Savvy proponents of Guan Yu-worship like Wei know his particular blend of zhongyi still has resonance today. Recent years have seen the rise of “cultural confidence” discourse in China, as the Communist Party promotes traditional culture as a source of creative inspiration and a way to foster a sense of belonging, identity, respect, and patriotism in the people.

The Haizhou Guandi Temple Conservation Institute is at the fringes of China’s state structure, but Wei has nevertheless made it his goal to answer this call. Over the years, he has often spoken to officials and entrepreneurs about the significance of “Lord Guan culture” to modern China: “Lord Guan’s loyalty to his country, benevolent treatment of others, faithfulness in bureaucratic affairs, righteous brotherhood, and bravery in battle line up perfectly with the core socialist values of patriotism, dedication, friendship, and integrity,” he says.

Wei is by no means the only one who sees things this way. In 2016, the local Shanxi Provincial Party Congress included “exploring the value of zhongyi in Lord Guan culture” in its annual work report.

Linking a man born over 1,800 years ago with the official ideology of the present day is a clear example of the politicization of history and religion. But then, history shows official China’s embrace of Guan Yu has always been political.

And just as commoners in imperial China had their own reasons for going along with his deification, the handwritten prayer cards at Yuncheng’s Guandi Temple offer evidence the same holds true today. The requests on display ranged from students hoping for success in the national college-entrance examination, to people praying for a promotion or money. One even called upon Guan Yu to take care of a personal grudge: “Down with deadbeats! Lock up Zhang Jialin and Hu Ruimin!”

The market, too, recognizes his popularity. Guan Yu’s image can be found in movies, cartoons, and video games; he’s even been reimagined as a Chinese Santa Claus.

Wei receives frequent inquiries from businesspeople looking to brand their latest product with Guan Yu’s famous mug, with some adopting unusual tactics to win him over. “Lord Guan came to me in a dream last night,” the boss of a baijiu liquor company once told Wei. “He told me that he’s fed up with the liquor he’s normally offered and wants to drink something different.”

Wei is generally cooperative when it comes to such requests, be it for watches, car ornaments, or bank cards — though he did once reject a proposed tie-in with a bedsheet manufacturer. “How could I allow people to take a ‘roll in the hay’ with Grandpa Guan?” he recalls.

Ultimately, however, that’s because he views these matters as unimportant: His focus is promoting Lord Guan as a highlight of traditional Chinese culture. “Politics is temporary,” he says. “And economics can be long or short. Only culture is eternal.”

Translator: David Ball; editor: Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Close-up of a wall portrait of Guan Yu taken at a Guandi Temple in Kaifeng, Henan province, Feb. 19, 2018. IC)