Why It’s So Hard to Overturn a Guilty Verdict in China — Even a Wrong One

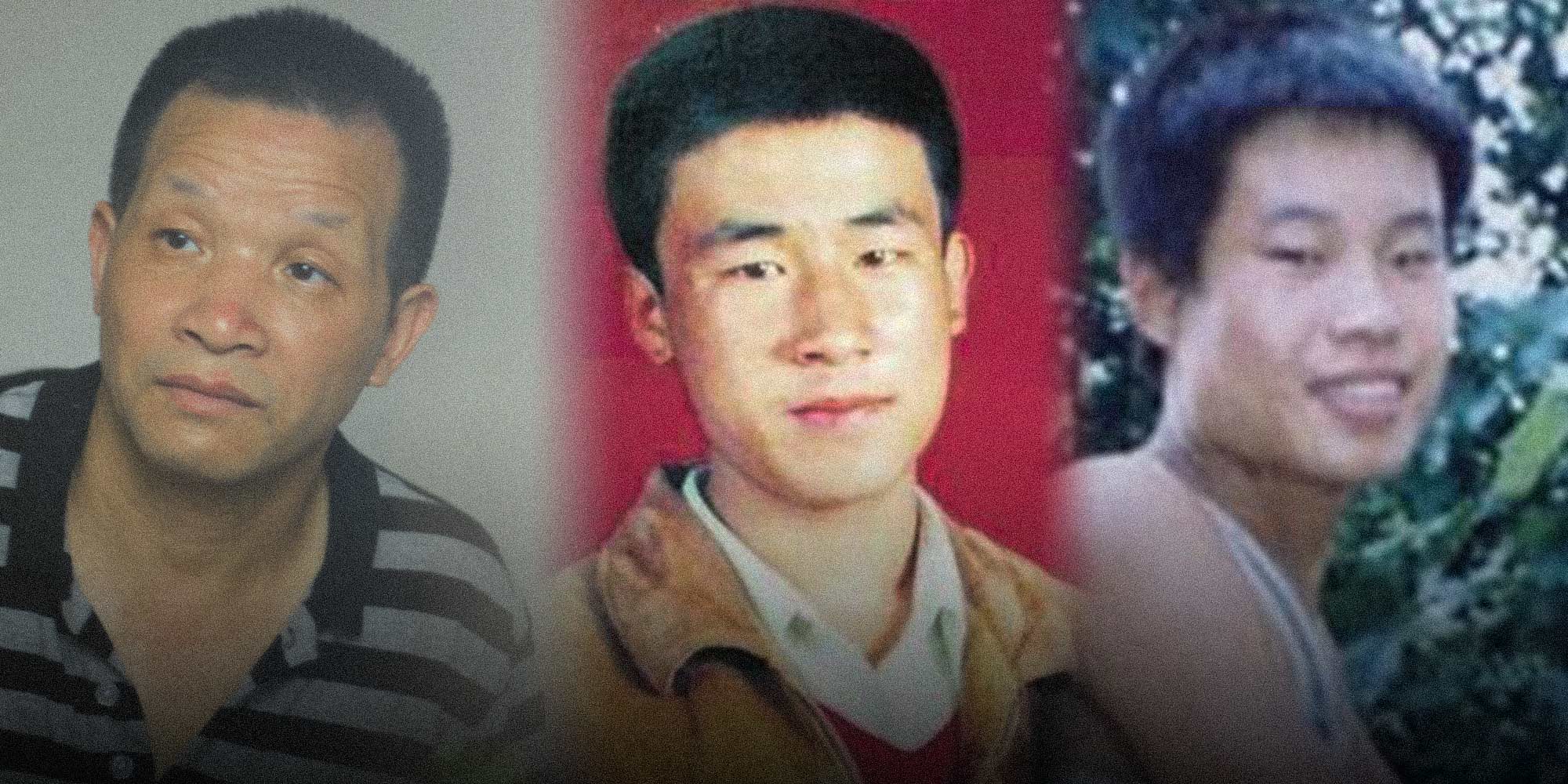

On Aug. 4, the High People’s Court of eastern China’s Jiangxi province acquitted Zhang Yuhuan of murder. Zhang was 26 when he was arrested for the killing of two children from his village in 1993. Over the next 27 years, he wrote more than 400 letters from prison, asking for his case to be retried. He also asserted that his admission of guilt was made under duress.

In recent years, China has increased its efforts to address wrongful convictions and build public confidence in the judicial system. Since 2012, China’s police, prosecutorial, and judicial departments have all issued documents on guarding against unjust, fake, and false charges. But Zhang’s 9,778 days in prison, the longest sentence served in China by a since-acquitted defendant, is a reminder of how hard it remains for those affected by these injustices to get their sentences reviewed.

In a 2018 study, I looked at 24 high-profile convictions that had been overturned by Chinese courts between 2012 and 2016. Two of the accused, Nie Shubin and Huugjilt, had been wrongfully convicted of rape and murder, but were executed before their names could be cleared. On average, the wrongfully convicted spent an average of 17 years behind bars before their release.

Why is it so hard to overturn a wrongful conviction? According to China’s Criminal Procedure Law, cases resulting in “erroneous rulings” should be retried and the defendants resentenced. These include convictions based on unreliable material evidence, depositions of dubious authenticity, or in which prosecutors failed to provide proof beyond reasonable doubt.

But many in the judicial system prefer to avoid retrials, for two reasons: They want to sidestep the accountability that falls on the police, prosecution, or the judge after redressing a wrongful conviction; and they worry that admitting to an erroneous ruling could impact community trust in the system itself.

In the Nie Shubin case, Zheng Chengyue — a deputy police chief who believed Nie had been wrongfully convicted — spent more than 10 years trying to get Nie’s sentence overturned, only to face significant backlash. Zhang Yuhuan mailed hundreds of letters asking for a retrial over the course of decades, after which it still took his lawyer another three years to get the appeal off the ground.

Oftentimes, it takes a perfect storm of factors to get a retrial approved: a steady stream of appeals from the defendant, as well as their family, lawyers, and even legal scholars, plus sustained media attention. In a statement, Jiangxi’s High People’s Court said their decision to overturn Zhang’s verdict arose from a belief in the presumption of innocence. That may be, but many of the recently overturned cases owed much to chance.

Seven of the 24 cases I studied were corrected only because the real perpetrator was later caught, forcing the courts to act. Ten years after Nie Shubin’s execution, another man, Wang Shujin, confessed to the crime while standing trial in another case. It would take another 11 years, but Wang’s unexpected confession ultimately compelled the courts to posthumously throw out Nie’s conviction.

Many wrongfully convicted defendants believe the standards for opening a retrial are unfairly high. Getting the courts to acknowledge an error of judgment requires more than just reasonable doubt: There must be evidence demonstrating the defendants’ innocence, like the discovery of the actual perpetrator. In one rape and murder case in Zhejiang, even though the DNA found on the victim’s fingernails did not match the defendants’ DNA, the court was still unwilling to grant a retrial. Only years later, when a DNA match was found, did the court overrule the two defendants’ sentences and find them innocent.

In addition to retrial barriers, those looking to redress wrongful convictions often run into technical difficulties, like poor evidence preservation. Because China has not yet established a comprehensive system for preserving trial evidence, it can vanish or even be concealed after a defendant is sentenced and imprisoned. The loss of the evidence makes it harder to disprove the description of a case and uncover facts that might support the defendant’s appeal. By the time the Nie Shubin case was put under review, key pieces of evidence had disappeared: the hair found on the victim’s clothing, the interrogation log taken five days before the trial, witness testimonies concerning the victim’s activities leading up to the crime, and the defendant’s attendance sheet at work. This posed major difficulties to overturning the sentence.

Nor does DNA play a major role in overturning wrongful convictions in China. Between 1989 and 2003, 42% of wrongful convictions in the U.S. were overturned based on DNA evidence. Of the 24 corrected cases I looked at, only one was reopened purely on the basis of DNA testing. In that instance, the police had apprehended a presumed “accomplice,” only to discover his DNA did not match a sample taken from the murder weapon. The discovery unearthed glaring holes in the case and drove them to reopen the investigation.

Such stories have spurred the correction of more wrongful convictions, including that of Zhang Yuhuan, who at least didn’t have to wait for authorities to find the real perpetrator. Still, correcting these cases will take persistence and a commitment to using all available technology. Going forward, China needs to lower the threshold for retrials, develop a system for evidence preservation, and dedicate more financial resources and technical support to putting right past wrongs.

Translator: Katherine Tse; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: From left to right, portraits of Zhang Yuhuan, Huugjilt, and Nie Shubin. People Visual and Weibo)