Modern ‘Ai’: Love and Socialism in Republican China

This is the second in a three-part series on the politics — and politicization — of love in modern China. The first can be found here.

He may not have known it, but when Che Guevara declared that “the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love,” he was echoing another of the 20th century’s leading architects of revolution: Sun Yat-sen.

After the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1912, China’s new, ostensibly republican rulers sought to create modern citizens who were devoted to their country. Patriotism — love for one’s nation — was a virtue, expressed through participation in ceremonies and rituals like bowing to the flag or shouting, “Long live the republic!”

Many of the country’s new elites were heavily influenced by Christianity. Among the 274 members elected to the first national parliament between December 1912 and January 1913, 60 were Christians — a rather large proportion, considering Christians accounted for less than 1% of China’s total population at the time.

While most of the traditional gentry were hostile to this imported faith, the younger generation had been trained in modern schools; many were merchants and urban professionals who were open to the idea of a “Christian Republic.” Even those who were not baptized or practicing Christians nonetheless embraced Christianity as a culturally and politically advanced ideology important for building modern institutions and infrastructure.

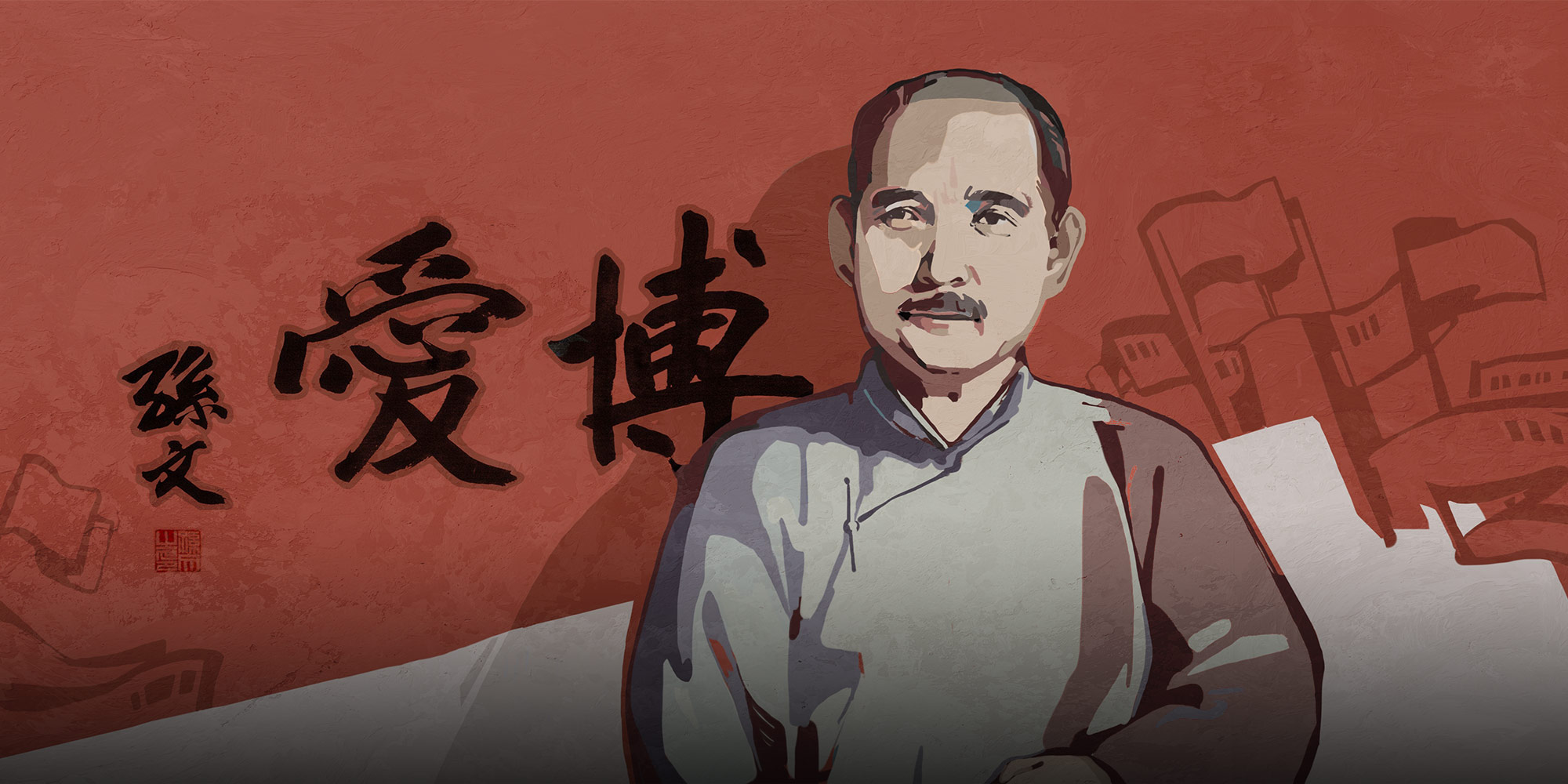

Sun Yat-sen, the founding father of the Republic of China, is a good example of this new Christian elite. Educated at a missionary school in China before studying abroad, Sun was not only familiar with the language and rhetoric of Christian love, he also adopted it in his politics and discourse. This is perhaps best exemplified by the repeated appearance of bo’ai, or “universal love,” in his calligraphy — a term some scholars claim was adapted from the Greek concept of virtuous love, agape.

Western missionaries were among the first to repurpose the Chinese character ai to mean “love” in the Christian sense. But while Sun publicly acknowledged his intellectual debts to Protestant modernism, it is also true that he tended to emphasize Christian influences when speaking to Western reporters, funders, and missionaries to raise money for his revolutions. If one looks closely at his politics, policies, and political philosophy, we can see many of his ideas are borrowed from and inspired by radical thinkers from Europe and elsewhere, rather than just Christian theology.

One of those thinkers was the American economist Henry George, best known for his 1879 work “Progress and Poverty.” Still, it’s fair to say that both Sun and George’s more radical ideas, especially pertaining to land reform, were often tinged with the rhetoric of Christian love. For example, Sun acknowledged that missionaries “put love into action by organizing schools and hospitals” and referred to Jesus as a “religious revolutionist.”

This distinguished Sun, as a leader of the Nationalist Party (KMT), from the more explicitly secular Chinese communists. Yet the communists, too, centered the rhetoric of love in their nationalist and modernizing project. In the words of Li Dazhao, one of the founders of the Communist Party of China (CPC), the meaning of communism was also bo’ai — interpreted as love among brothers and compatriots. Chen Duxiu, the co-founder and first secretary-general of the CPC, also proclaimed the task facing China’s intellectuals was to create a society that was sincere, progressive, free, egalitarian, and full of universal love.

Such expressions were no less common among the radical youth who were seeking ways to oppose not only Confucian traditions, but also the Nationalist government led by Sun’s successor, Chiang Kai-shek, who rejected Sun’s democratic socialism and became a corrupted, authoritarian, and repressive leader.

One of those radical youngsters was author Ding Ling, a female writer who rose to fame during the Republican era. In her novella, “Miss Sophie’s Diary,” the protagonist doubts “What the world calls love … and the love she’s received.” Ding’s quest for love was answered by the Communist movement, and she was later further radicalized by the execution of her lover Hu Yepin by the Nationalist government in 1931. Afterward, she began writing more fiction and texts in favor of the CPC’s ideals.

For young revolutionaries, the older generation spoke only of revolution’s political dimensions, not of society, the freedom to make one’s own decisions, or social and economic equality. What passionate, rebellious young people like Ding Ling found in left-wing sentimental discourse was not merely a representation or an expression of their inner emotions, but a powerful means of putting their ideals into practice, one that would allow them to participate in redefining the social order and, eventually, building a new China.

Over time, the rise of the CPC entrenched opposition to Christian and foreign influences. Sun Yat-sen never convinced Chinese intellectuals to trust in his pragmatic hybrid of Christianity and socialism, and history shows other revolutionaries eventually chose the CPC and secularism over Sun’s KMT and syncretism.

Nevertheless, and despite the country’s ensuing civil war, Sun’s bo’ai theory of universal love represents a point of intersection between the two parties. It’s also a reminder of how, during the turbid years following the birth of the Republic of China, the meaning of this ostensibly Christian term grew increasingly radical and socialist.

Editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Wang Zhenhao for Sixth Tone)