Future Nostalgia: China’s Video Games Plug Into Ancient Culture

After his real estate startup collapsed in 2014, Tian Haibo was left devastated and unsure what to do next. Then, he made a decision that caught many off guard.

He would create a mobile game to teach the world about the ancient art of Chinese joinery.

It has taken nearly six years for the 36-year-old to teach himself to code, assemble a team, and bring his vision to life. But after a few false starts and 5 million yuan ($740,000) of investment, the game finally launched in June.

In Mortise & Tenon, players carve complex joints into floating blocks of wood, so the lumber can slot together tightly. Chinese craftspeople have been constructing buildings using this nail-free technique — known as sunmao in Chinese — for an estimated 7,000 years.

The gameplay is decidedly low-thrill — akin to a 3D version of Tetris, but slower and set to soothing instrumental music. Some have also commented that a shortage of levels somewhat detracts from the experience.

But China’s gamers love it. On the app store TapTap, Mortise & Tenon has an average rating of 9.1 out of 10 from over 5,000 reviews, and it has already been downloaded over 2 million times across Chinese app platforms.

The secret to the game’s success has been its appeal to patriotic users happy to see an unsung national treasure represented with such care and creativity. In the product description, Tian sets out his mission clearly.

“I hope to lend my strength to passing on sunmao culture,” he writes. “To introduce it in a way that young people like. … And to let more people know that China is the coolest.”

It’s a formula that’s becoming increasingly common in China’s gaming industry. While domestic developers have always drawn on the country’s rich culture and history, a striking number of video games are now being created — or updated — with the express aim of promoting China’s cultural heritage.

For gaming companies, adding traditional content into their products has become a lucrative way to tap into the growing fashion for all things ancient in China. It also has the added benefit of aligning with the government’s push for “national rejuvenation.”

A scroll through TapTap reveals pages of recently developed mobile games centered around Peking opera, Chinese poetry, ancient art, festivals, and many other native traditions. In one game titled Shadow Puppet: Three Kingdoms, users control a traditional Chinese shadow puppet, beating up enemies and flying around a digitally recreated stage.

“Shadow puppetry is … a precious treasure given to us by the ancients,” reads the product introduction. “Would it be possible to combine shadow puppetry with games, to make young people understand our China’s awesome 5,000 years of culture — while also having fun?”

Indie titles like these remain niche, but they’ve found a market thanks to the sheer scale of China’s video game market, Tian tells Sixth Tone. In 2019, the country had 640 million gamers and its gaming companies made $33.1 billion in revenue.

Major developers like Tencent and NetEase, meanwhile, are competing to integrate aspects of ancient China into their existing franchises. To do this, they’re forming alliances with leading museums and cultural institutes, which help the tech companies create in-game content based on well-known historical artifacts, traditions, and monuments.

Tencent’s hugely popular mobile battle game Honour of Kings, for example, has used this approach to develop a slew of traditional costumes. Players can now dress characters in outfits inspired by the famous murals in northwestern China’s Mogao Grottoes, the southern Chinese tradition of lion dancing, as well as several forms of Chinese opera.

To coincide with Qingming Festival this April, Honour of Kings worked with a research institute in the eastern Shandong province to introduce players to the local tradition of kite-making. Players could fly virtual Weifang kites and view documentaries and livestreams about the craft that were accessible in-game.

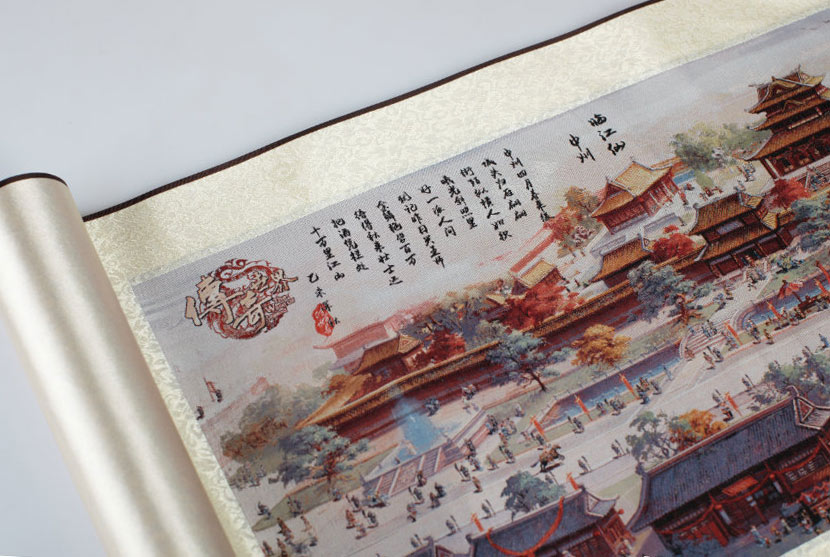

The same month, NetEase’s Ni Shui Han — a World of Warcraft-like game set in Song dynasty China — added in-game Chinese opera performances, which the game had recreated by recording several top opera singers using motion capture technology.

“We must resolutely keep walking the path of passing on China’s cultural essence!” the game declared in a post introducing the new feature on the social platform Weibo.

Other games have launched similar initiatives in collaboration with cultural heritage “inheritors” — practitioners of traditional artforms that receive government support to popularize their crafts.

The online game World of Legend partnered with inheritors to add features based on the ancient art of Dingxi paper-cutting, Daoqing shadow puppetry, and Huizhou bamboo carving, while mobile game Jade Dynasty created new in-game weapons after consulting with an inheritor of the 2,500-year-old Longquan sword-making tradition.

For the developers, this dive into culture is about more than simple altruism. “Freemium” games like Honour of Kings have generated enormous profits by convincing players to purchase in-game add-ons, such as special character costumes. The Tencent-produced title made $4.5 billion between its launch and March 2019.

Zhao Yanlin, managing editor of Chinese gaming media Gcores, tells Sixth Tone the tie-ins are part of the game industry’s cross-industry marketing tactics, which companies use to keep users playing — and paying.

“If a game has particular elements, they’ll seek to cooperate with organizations that share elements with them but are outside their circle,” says Zhao. “They’re in need of topics.”

New additions like the Mogao Grottoes-inspired skin — price: 58.80 yuan — are a response to the upsurge of interest in traditional culture among young Chinese. This is epitomized by the rise of hanfu — a style of clothing loosely based on garments worn by China’s Han ethnic group during ancient times — which has grown into a large youth subculture and a 1 billion yuan industry.

China’s museums have also benefitted from this trend, with many finding success peddling their own branded products to millennials via online stores. Beijing’s Palace Museum alone has developed over 10,000 different consumer items, and once sold 100,000 tubes of Forbidden City lipstick over just four days in 2018.

Television networks, meanwhile, have scored surprise hits with shows about antiques, as well as game shows testing contestants’ knowledge of Chinese and poetry. Costume dramas set in imperial courts have also drawn huge audiences — the most successful of all, “Story of Yanxi Palace,” was briefly the world’s most Googled TV drama.

In some cases, video games have even begun partnering with historical TV shows to generate publicity. Earlier this year, Ni Shui Han linked up with the palace drama “Serenade of Peaceful Joy” to make the characters’ elaborate costumes available to gamers.

“It’s actually a supply and demand relationship,” says Tian. “The demand for culture among China’s young people has increased … which means more companies will choose to do this kind of content.”

The Chinese government’s strict management of the gaming industry, however, is also a factor. Over recent years, developers have been banned from using various types of content in games — even blood, which is now often rendered as blue or green gunk.

In such a tight regulatory environment, plugging traditional culture into games can help give products a positive sheen. It also aligns with government priorities: preserving China’s cultural heritage, increasing the country’s “cultural confidence,” and expanding the influence of Chinese culture worldwide.

The potential for video games to become a Chinese soft power tool has been a hot topic at media and gaming conferences since around 2016, when Tencent acquired a majority stake in the Finnish developer Supercell for $8.6 billion — which cemented its place as the highest-earning game company in the world.

On the sidelines of a 2018 conference in Indonesia, Yuan Jing, the head of Shanghai-based developer Moonton, told Chinese media of the firm’s ambitions to promote China’s culture among gamers overseas, just as Chinese gamers had learned about Western mythology through titles like the God of War series.

He pointed to how the roster of playable heroes in Moonton’s team battle game Mobile Legends: Bang Bang — which at the time had 250 million registered players across Southeast Asia — featured characters inspired by Chinese culture and history.

“After exporting games abroad, we implant them with cultural elements,” Yuan said. “Through games, we will subconsciously influence gamers around the world with traditional Chinese culture.”

Yet this push isn’t simply a top-down, government-driven campaign. Independent developers express similar sentiments, which often stem from a genuine concern that many aspects of Chinese culture are little-known and quickly vanishing.

Tian tells Sixth Tone he was inspired to make Mortise & Tenon six years ago, after reading a magazine article praising a Japanese-designed building in Switzerland that made use of sunmao. To Tian, it felt like Japan was getting credit for a Chinese invention.

In the ’00s, Tian had lived in Canada and the Middle East for several years, and he’d developed a keen sense for how people abroad often overlooked Chinese culture. In one particularly hurtful incident, he’d been in line at a Korean restaurant in Canada when a local approached him, assuming he was from South Korea or Japan. As soon as the person learned Tian was from China, however, they’d turned their back and walked away without a word.

After discussing the encounter with friends, Tian eventually concluded the person had acted so rudely because they didn’t understand China. While Japan was known for its anime and South Korea was rocking the world with its pop music, his home country had produced few widely admired cultural exports.

For Tian, video games could be the solution. After the collapse of his real estate company in 2014, he decided to found a startup which would focus on producing games to spread awareness of Chinese heritage. He eventually settled the new venture in the southwestern city of Chengdu and called it EBGame, or Dongji Liugan in Chinese — a name meaning “feeling Eastern culture with your six senses.”

“As long as you’re trying to beat culture into people’s heads, they won’t accept it,” says Tian. “But with games, you can make game-loving youth learn a little about traditional culture while they’re relaxing.”

Mortise & Tenon is the company’s first attempt at putting this theory into practice. Getting to this point, however, hasn’t been easy. Tian has had to deal with constant financial difficulties and has seen numerous team members quit. He himself has been on the verge of giving up several times, he says.

What kept Tian going was the encouragement of the Palace Museum’s deputy dean, Feng Nai’en, who praised an early version of Mortise & Tenon after the game won a design competition held by the museum and Tencent in 2016.

“Dean Feng told me the game made good use of its source material and that he hoped I could carry on with it,” says Tian. “At the time I thought: ‘Even the Forbidden City wants me to finish it! I must complete it!’”

After the game’s release in June, Tian says he felt vindicated by the overwhelmingly positive feedback — one student even told him the game inspired him to change his college major to ancient building restoration — but he’s only recouped 1 million yuan in revenues so far. On Oct. 1, he’ll also release an English version of Mortise & Tenon to international app stores.

How overseas gamers respond to this kind of game, however, remains to be seen. Despite recent discussions of a soft power push, the Chinese titles that have broken through internationally over recent years have often had little to do with ancient China.

The mobile version of PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds — one of Tencent’s biggest hits — is set in the modern day and has no discernible Chinese elements. Most other globally popular Chinese mobile games are set in European-style fantasy worlds.

Conversely, the world’s biggest China-themed video games aren’t Chinese creations at all. Total War: Three Kingdoms — the hit strategy game based on “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” — was made by the British outfit Creative Assembly. The long-enduring hack-and-slash franchise Dynasty Warriors was produced in Japan.

Instead, China’s influence may end up spreading through games when it’s not trying at all. Zhao, the Gcores editor, argues that cultural propagation tends to be the natural result of a nation’s superior economic performance. He references the United States’ dominance today, the popularity of Japanese anime and games in the ’80s and ’90s, and China’s cultural clout during the Tang dynasty some 1,400 years ago.

The release of a demo for the upcoming game Black Myth: Wukong last month appeared to offer a glimpse of this future. Produced by Game Science, an independent Chinese developer, the video caused a sensation both in China and abroad, receiving millions of views on YouTube.

The video showed a beautifully rendered Sun Wukong — the Monkey King from the classic novel “Journey to the West” — shape-shifting, fighting enemies, and exploring a forest, lush fur rippling in the breeze. It was a rare example of a single-player Chinese game produced with world-class graphics — and it triggered much excited discussion among Chinese commentators, who were delighted to see people abroad discussing one of China’s most popular folk tales.

For the game’s developer, however, the attention Black Myth: Wukong has received has been bewildering. In an interview with Shanghai news media Guancha.cn conducted soon after the video’s release, Feng Ji, Game Science’s controversial CEO, said the team had little interest in promoting Chinese culture.

“When we decided to do this project, we didn’t at all have ideas like, ‘I want to represent Chinese culture,’” says Feng. “We’re Chinese. We were born here. We naturally have a feel for these things.”

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: A promotional image for NetEase’s game Ni Shui Han. From @逆水寒 on Weibo)