How COVID-19 Border Controls Split China’s Transnational Families

Ran is Chinese. His wife, Juri, is Japanese. Married for three years, they’ve spent the past year living apart: Ran in the eastern Chinese city of Wenzhou and Juri in Tokyo, where she was studying for her master’s degree.

In March 2020, two months into the COVID-19 pandemic, Ran accompanied Juri to the airport for her flight back to Japan, where she would defend her thesis. Ran had hoped to follow his wife abroad once the pandemic abated in China, but their plans soon went awry. On March 9, following a sharp uptick in the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Japan, the country effectively barred most Chinese citizens from entry.

Around the same time, the couple received some happier news: Juri was pregnant. She wanted to give birth in China, where she would have the support of her husband and his family. As the outbreak gradually subsided on the Chinese mainland, she booked a flight from Japan for early April. But in the last week of March, with COVID-19 cases spiking around the world, it was China’s turn to bar foreigners from entry. The sweeping policy, which went into effect on March 28, allowed exemptions only for diplomatic, official, humanitarian, and a select few other purposes.

Juri emailed the Chinese consulate in Tokyo, describing her family’s plight in hopes of obtaining a visa via the humanitarian exemption. However, she was informed that only “the death or imminent death of immediate family members” would be considered a legitimate basis for such an application. Juri’s request was denied.

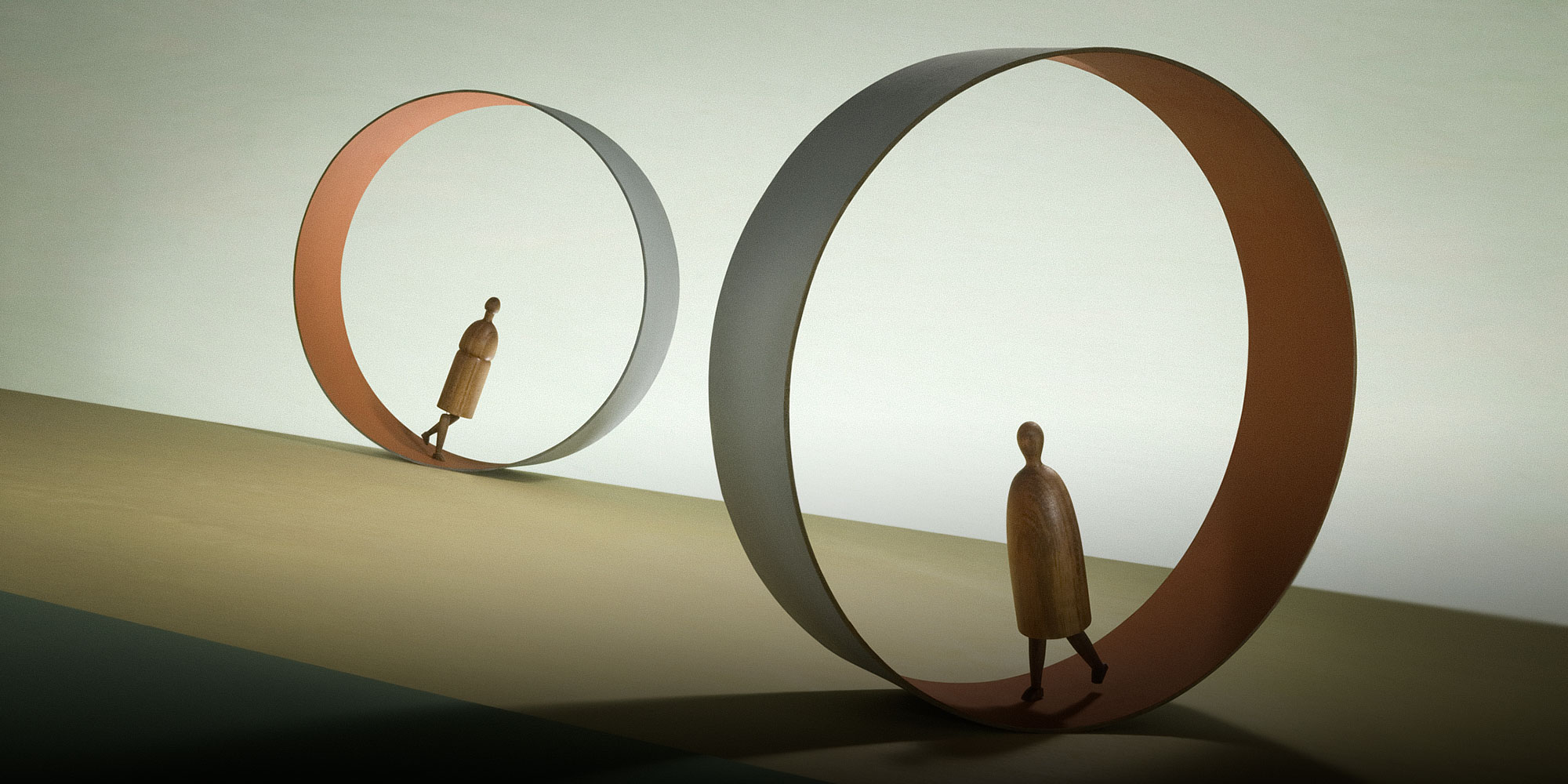

Over the past nine months, there have been countless cases like Ran and Juri’s, in which mixed-nationality families have been separated or kept apart by new, pandemic-driven immigration policies. The problems with these policies are to an extent understandable, given the haste with which they were adopted. But their bitter fruits have prompted some in China and around the world to ask broader questions about how border control regimes reflect a country’s treatment and conceptualization of transnational or mixed identities, as well as how these identities can be served and protected in more flexible and humane ways.

China is not alone in having implemented strict border controls. In denying entry to almost anyone without a Chinese passport — including long-term residents, immediate family members of citizens, and foreign nationals studying or working in the country — its approach has mirrored that of other countries such as Vietnam, Thailand, Russia, and Laos. This might have been easier to bear if China recognized dual citizenship or was less stingy in its issuance of green cards. As it stands, however, the sudden suspension of visa-based entry effectively cut tens of thousands of people off from their schools, places of work, and loved ones.

Aran is a citizen of the European Union. Born in the eastern Zhejiang province, he is currently researching communities along China’s southeastern coast. He told me that the pandemic and ensuing travel bans had given him a new perspective on his doctoral project, which relates to Chinese identity, diplomacy, and soft power.

Aran, who had been visiting Taiwan for the Lunar New Year when COVID-19 turned his short trip into a six-month stay, saw the Chinese mainland’s strict entry controls as a stress response stemming from having witnessed the initial outbreak and fears related to its large and mobile population. But he also thinks the decision may have been related to China’s proportionally small immigrant population, a demographic pattern shared by many East Asian countries. He suggested that the Chinese mainland could have instead tied entry to visa categories, as the European Union did. This would have enabled residence permit holders including students, workers, and spouses to re-enter the country.

Debates over whether and how to reform the country’s immigration and residency rules are a relatively new issue in China. Already the world’s most populous nation, efforts to enact laws giving permanent residency to greater numbers of foreigners have typically been met by fierce backlash from a public unconvinced of the need for more people. But where does that leave couples like Ran and Juri? And what of those accustomed to straddling two or more cultures?

Pre-coronavirus, the ease of international travel gave many transnational individuals a false sense of security. They believed they could work freely and balance their lives between different societies, regardless of their formal nationality.

Jun, a 20-year-old college student of Chinese and Japanese descent, was caught off guard by the realization that the word “foreigner” in the March 28 notice applied to him. Jun’s parents live in Shanghai, and he spent six years in the city’s secondary schools. Yet, despite being fluent in Chinese and treated by his Chinese acquaintances as “one of us,” his Japanese passport effectively rendered his “idealized and romanticized” dual identity useless this spring, when he found himself cut off from his parents by the new entry rules.

The ideals of globalization — openness, inclusivity, and the possibility of multifaceted and mixed identity — are currently under siege, and previously mobile individuals are having to adapt or re-adapt to a world of closed borders. When I spoke to them, Juri and Ran were already mentally preparing for a long separation. “I really want to go back to China, and I really miss my husband and family,” Juri told me. “But maybe the best thing for the baby is for me to just stay where I am.”

It may not come to that. This month, China announced it would finally begin allowing residence permit holders back into the country from Sept. 28. Still, the past few months should be a wake-up call. For years, countries trumpeted the virtues of globalization. Millions took these affirmations at face value, only to have the rug pulled from under them. Even amid a pandemic, we have every reason to expect nations to recognize the challenges faced by these individuals, and to help them reunite with their loved ones.

The author has used pseudonyms to protect the privacy of his research participants.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

(Header image: E+/People Visual)