China’s Middle-Aged Dudes Embrace ‘Son-in-Law’ Lit

Imagine you’re a man living in your wife’s parents’ home, where you’re constantly berated for what the matriarch of the household judges to be an inadequate income and a defective personality. Then one day, you find you’re no longer a nobody — instead, you’re the heir to the wealthiest clan in the city, have awakened a latent superpower, and the world as you knew takes a dramatic turn in the blink of an eye.

Strange as it sounds, this is a popular plot on China’s online fiction platforms. It even has its own label: the “live-in son-in-law” saga. Since 2018, this genre of online novels has become one of the most popular in China’s web fiction industry, according to Initium Media, a Hong Kong-based digital outlet.

When it comes to online fiction, China boasts an enormous readership. As of last year, over half of the country’s 854 million internet users read online fiction on their mobile phones, and an overwhelming majority of readers — over 70% — are born after 1990, according to official estimates. Growing demand has led to a booming online fiction market, with content ranging from wuxia martial arts epics to playful time-traveling tales and boys’ love romances.

Live-in son-in-law stories have become more popular in recent years as mobile internet reached less-developed regions of China, An Xiaoliang, a writer of popular science and critic of online literature, told Sixth Tone. Many fiction websites — especially free ones — now publish live-in son-in-law stories. “On many free fiction websites, they’re the top-ranking novels,” he said.

In a typical live-in son-in-law story, the protagonist is a scorned dog to his wife’s family. As the plot progresses, however, he gradually earns the respect of those who perpetually dismissed him — and, more importantly, the love of his wife as he evolves into a worthier mate. In many cases, the character’s odds of success are improved by the discovery that he has superpowers.

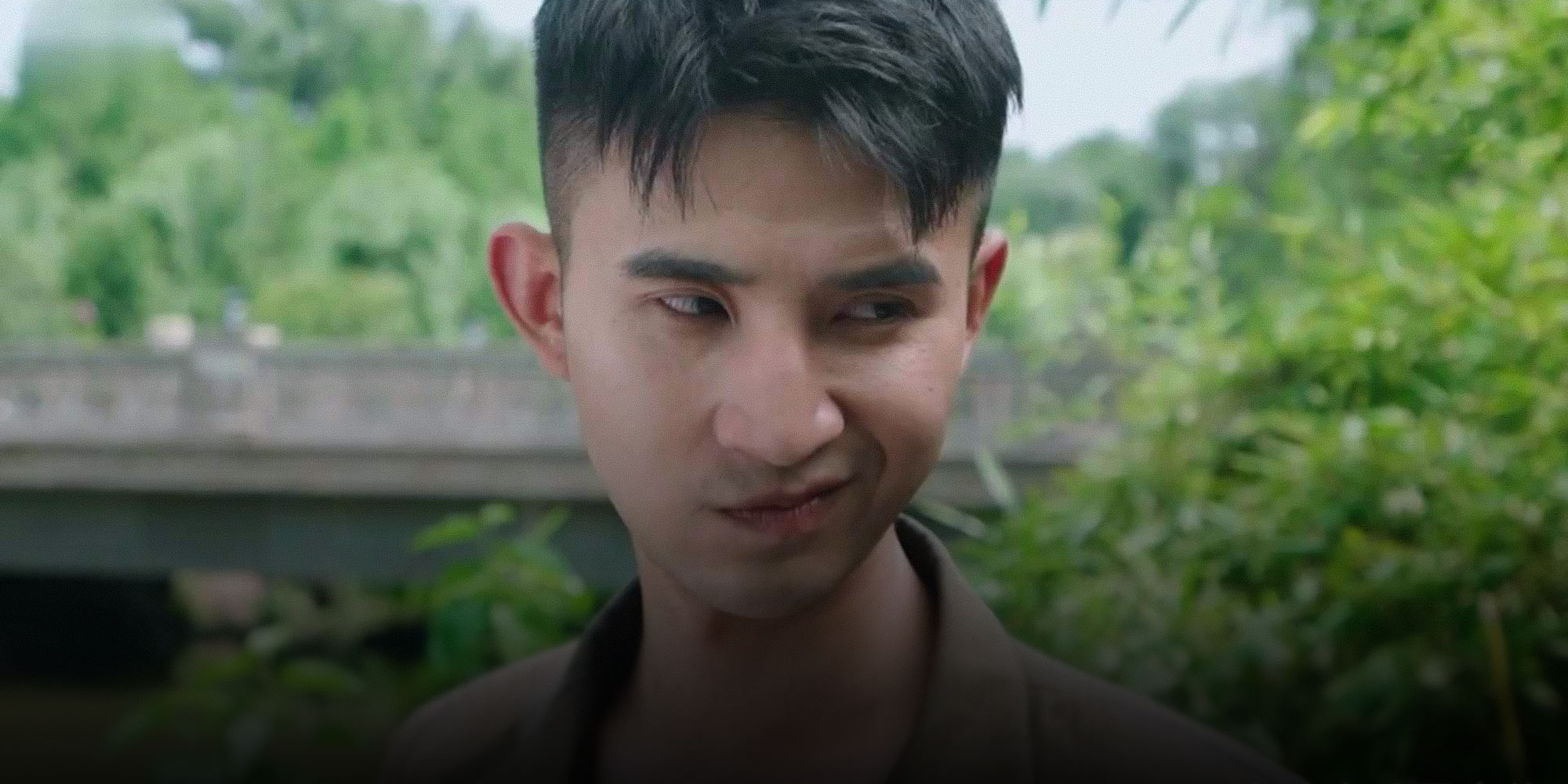

The surging popularity of son-in-law stories follows a series of short videos — an increasingly common medium for promoting online fiction — that went viral in July. In them, actor Guan Yunpeng portrays a variety of different sons-in-law who find themselves stuck in Cinderella-like circumstances. As a result, Guan has become the unofficial face of the genre. On Chinese microblogging site Weibo, his videos have been viewed over 2 million times, while on video-sharing platform Bilibili, his trademark facial expression — half smirk, half sneer — has given birth to a host of memes and spinoff videos involving more recognizable figures, including Japanese sci-fi hero Ultraman and Patrick, the quixotic starfish from SpongeBob SquarePants.

In China’s staunchly patriarchal society, it is more common for a woman to live in a man’s household after marriage, as men are the traditional breadwinners. As such, moving into the wife’s household is sometimes viewed as emasculating — for, the antiquated logic goes, only men who are too incompetent to provide for their families would need to rely on their wives’ parents for support.

Perhaps unexpectedly, the relatively new live-in son-in-law genre has attracted a large number of middle-aged male readers, many of whom are married and live in less-developed cities, an online fiction editor told Initium. An, the writer and critic, echoed these observations.

“My conversations with editors reflect that, generally, older readers like those stories (about live-in sons-in-law), while younger people prefer fantasies,” An told Sixth Tone. “Many middle-aged men who’ve spent half their lives thinking they’re being bullied by their wife and father-in-law often imagine that one day they will stage a great coup.”

Before the rise of this new genre, the middle-aged male demographic had a predilection for political fiction, but a steady decline in such titles due to authorities’ increasingly strict regulations has led them to look elsewhere for diversion, according to An.

Ji Yunfei, an internet literature researcher at Peking University, told Initum that the rise of the live-in son-in-law stories may be attributed to the oft-ignored emotional needs of China’s middle-aged man — a so-called silent group when it comes to expressing their struggles and desires.

“For any kind of popular literature phenomenon, you may think that the work is of limited quality — but underneath the surface, it must have touched upon the anxiety and desire of a generation,” Ji was quoted as saying.

While son-in-law stories are popular now, An isn’t confident that they will endure if the authors continue to fall back on the same cookie-cutter templates time and again. “Personally, they all look the same to me, in terms of both content and style,” he said. “They’re like fast-food products, lacking depth.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: A still frame from the “live-in son-in-law” video series starring Guan Yuanpeng. From AcFun)