Shanghai’s Urban Scavengers Rescue Memories of a Vanishing City

SHANGHAI — Undeterred by a foul, musty odor, Li Zhichen enters a dilapidated house in search of a particular kind of treasure. Once inside, he scours through piles of splintered lumber, under broken chairs, and behind a rotting sofa. Among the rubble, an unassuming flower-patterned glass bottle piques his interest. He picks it up, wipes off the dust with his hands, and holds it in a beam of sunlight.

“The art deco aesthetic is very unique to its time,” Li muses, referring to a design style popular in Shanghai during the early 20th century. “The family must have been very thrifty to keep it for so long.”

Li’s hunting grounds are the more than 1,200 abandoned houses of Maoyi Li, a once-bustling lane community in Shanghai’s Huangpu District that is slated to be demolished soon. Red banners and official bulletins cover the stucco walls, carrying messages urging the residents to accept resettlement packages. Nearly all households have already relocated, taking along their family heirlooms and electronics. They leave behind other heavy objects like plants and Buddha statues, which pile up along the narrow alleys to be picked up later.

But Li is after what the former residents left behind inside their houses: empty bottles, faded posters, disembodied toys — their castoffs. “Every object left by the former residents has a distinct story to it,” he tells Sixth Tone during a scavenging trip in August. “It must have been passed through many people’s hands before reaching mine. It’s priceless to me.”

Since the early 1990s, about 90% of Shanghai’s characteristic but often cramped and decrepit lane neighborhoods have been torn down to make way for office towers, shopping malls, and apartment blocks that offer much-improved living conditions.

But with this history already disappearing, more people — and even the government — are trying to save what they can. Li, 30, is part of a small but budding community of artists, photographers, and history aficionados who flock to Shanghai’s demolition sites. Just before houses there are knocked down, the “urban scavengers,” as many call themselves, swoop in to look for leftover curiosities or take last-chance photos, thus preserving the traces of bygone eras before they vanish forever. Enterprising community members have even turned the fruits of their hobbying into side businesses and art exhibitions.

Some scavengers felt twinges of regret at the city’s rapid transformation earlier than others. “Around 2000, everywhere the eye could see were cranes, scaffolding, broken walls, and mountains of waste,” Xu Haifeng, a photographer for Sixth Tone’s sister publication The Paper, recalls. “It felt like the city was at war.”

Xu, now 51, has been documenting Shanghai’s lane neighborhoods for over 30 years. He is charmed by their mixture of Chinese and European elements — reminders of a time when much of Shanghai was carved into international settlements. During his trips to demolition sites, he often encounters Chinese-style wooden furniture pieces sharing rooms with European-style fireplaces, or staircases decorated with elaborate columns and floors tiled in mosaic patterns. These juxtapositions tell the vestiges of Shanghai’s colonial past, Xu says.

Xu doesn’t just take photos. Whenever he comes across salvageable objects that residents have left behind — a leather suitcase that only needs a trip to the cleaners, toys that just need some polishing up, even appliances that can still be fixed — Xu will take them home. He now has an entire room dedicated to his collection.

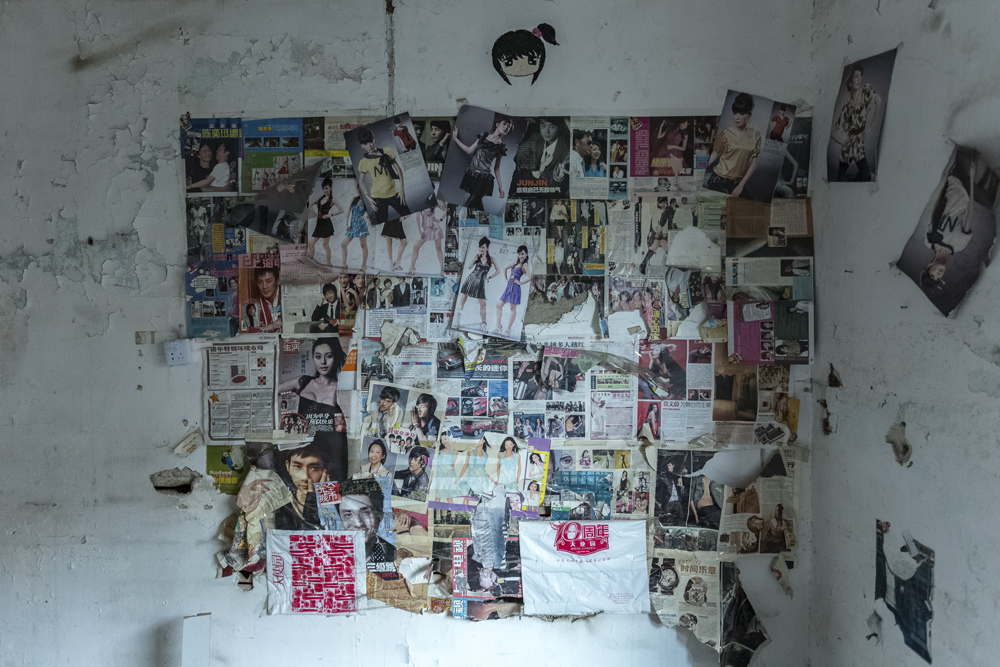

Some abandoned houses can tell the story of a family through generations. “It is like decoding an enigma,” he says. “A guitar, an oil painting, a diary … every item leaves you with some kind of clue.” Xu often encounters walls with all kinds of decorations clinging tightly to them — faded propaganda posters mark the social unrest of the Mao era, while movie star portraits, fashion magazine cutouts, and pornographic images are emblematic of the rising consumer culture during the subsequent reform era.

Many items are often well-preserved due to the elder generations’ tendency to hoard, Xi Wenlei, 51, another Shanghai-based photographer, says. It’s a habit he attributes to their experiences living through economic hardship. In his photos, a cassette player, a boombox, and a modern speaker are piled up in the same room. Three different clocks hang on the same wall, each a different design, marking the passage of time in more than one way.

Xi speculates that people leave those items behind partly because younger generations don’t appreciate their value, but also because, once the resettlement programs are announced, there is little time before the bulldozers arrive. The gap can be shorter than 10 days, he says.

More and more people of younger generations are drawn to the sites where Old Shanghai can be seen vanishing before their eyes. While other countries have subcultures of people fascinated with exploring buildings abandoned to the elements, he points out, the Chinese situation is unique in how fast houses can go from places full of life to abandoned ruins — and then, not long after, rubble. “They are not ruins handed down from the past,” Xi says. “They don’t experience any natural disasters — fires, hurricanes, earthquakes. They are products of our own contemporary society.”

Some have scavenged so successfully, they have become well-known figures in the community. Dong Xiongfei — nicknamed Geli, an old Shanghainese loanword meaning colleague — has an impressive collection of everyday items, from classic plastic hairpins to old telephone directories.

Among the more bizarre items in the 40-year-old’s collection are three unopened, decades-old bottles of Aquarius, a locally manufactured soda cherished by many Shanghainese for its distinct orange flavor. “A friend of mine opened a bottle and took a sip several days ago,” Dong says with a laugh. “Last time I checked, he was still alive.”

Shanghai’s rapid succession of urban renewal projects often makes Dong feel alienated in neighborhoods he used to know like the back of his hand. He laments the loss of intimate, tight-knit lane communities, and wants to record their existence before they are wiped out from city maps forever.

Dong started regularly visiting demolition sites with a crowbar in his backpack. After the residents move out, he pockets the door plates as the last memorabilia of these streets. He now has more than 100 of the bright green metal plates — his proudest collection. “The door plates are a reminder of the loss of the communities they had once been attached to,” Dong says.

Many urban scavengers are pragmatic about redevelopment projects. While some residents are forced to relocate against their will, others welcome the prospect, which usually means they will be compensated with larger though less centrally located apartments.

When Xu’s lane neighborhood was designated for urban renewal about a decade ago, the photographer was resistant to the idea. But then one night, a rat chewed through electric wires in the kitchen, causing the refrigerator to catch fire. He and his family had to climb down from the balcony to escape. The experience turned Xu’s attitude around. “The house was humid, cramped, and dusty,” Xu recalls. “I can still smell the odor from the staircase when I think of it now.”

But Xu feels a growing isolation from his surroundings after moving into his new apartment. He reminisces about the time when all the children gathered around the only radio receiver in the neighborhood, or when a film screening was organized in the lane. Now, he barely knows his neighbors.

Xu, Dong, and Li have all organized exhibitions to share their collections with the public. Dong’s has even been on display in Germany. He also designs and sells merchandise like T-shirts and tote bags with the prints of the items he has found.

Yet others have found that selling items on antique markets can also be a lucrative source of income. Such professional scavengers might scour demolition sites for days, gathering anything they can find with historical significance or bygone aesthetics.

Li sometimes sells things he’s not particularly fond of, but he couldn’t part with his favorite finds, he says. A kind of intimacy has grown between him and the objects: Having rescued them from total destruction, he feels he is obliged to bring them back to life again.

“Everything has its own place to go,” Li says. “Instead of letting them be destroyed by bulldozers, we give them a last chance to shine.”

Editor: Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: The interior of a home slated for demolition in Shanghai, 2015. Courtesy of Xi Wenlei)