Young Chinese Bemoan Rat Race With Tongue-in-Cheek Memes

Facing a bleak job market exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s young workers are embracing online expressions of ironic “optimism” to stave off creeping disillusionment.

The phenomenon was recently amplified by a redubbed clip on Bilibili — a video-sharing platform that’s especially popular with China’s Gen Zers, or those born after the late ’90s — featuring two characters from an Italian-Japanese cartoon. “Are you tired?” one of the characters, Enrico, wonders aloud after meeting up with his classmate. “It’s only natural to feel tired!” he tells himself. “Comfort is a luxury that belongs to the rich. Laborers, take heart!”

In another scene, Enrico muses: “There are two exceptionally dazzling lights in this world. The first is sunshine, and the other is the face of a diligent laborer!”

As the classmate gradually embraces Enrico’s labor philosophy, he begins to find motivation in the prospect of pleasing his superiors. “As long as we work hard, our boss will soon be able to live the life he wants!” he says, without a hint of sarcasm.

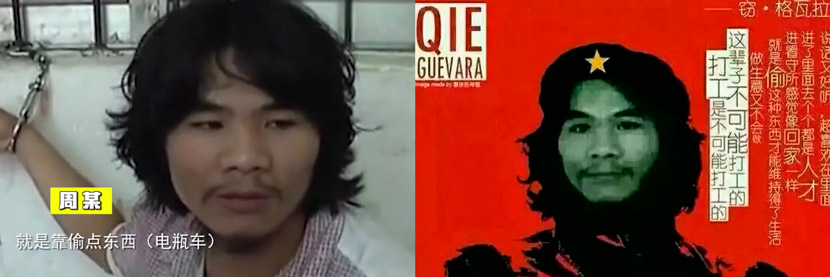

The netizen-made video — titled “Laborers, Take Heart!” — has become an online sensation, with over 2.2 million views and 97,000 likes since it was uploaded a week ago. The term “laborer” has subsequently become the latest buzzword on Chinese social media, along with similar phrases such as dagong zai (“migrant worker”), ban zhuan (“brick movers”), shechu (“corporate cattle”), and jiaban gou (“overtime dog”).

Many internet users say the video underscores grassroots workers’ gripes about stress and less-than-ideal working conditions, and uses terms like “laborer” — applied to all kinds of employees, from blue-collar workers and low-level staff to middle managers and top executives — in contexts that seem alternately uplifting, aspirational, and self-deprecating.

“This means more and more people are realizing that the splendor of tall buildings and the glory of companies doesn’t belong to them,” read one post by an online human resources company on Q&A platform Zhihu. “There’s no difference between white-collar workers in office cubicles and blue-collar workers on assembly lines.”

Here’s a selection of the buzzwords circulating in China’s latest online discussion on labor, along with a brief description of each group’s hypothetical relationship with their employer.

dagong zai (打工仔): the migrant worker

Dagong zai usually refers to young workers who move from the countryside to large cities to seek their fortunes, especially in manual-labor industries like construction and manufacturing.

Derived from Cantonese, the term predates the modern internet, tracing back to the 1980s, when China’s reform and opening-up policies introduced market principles to the domestic economy, welcomed foreign investment, and created more jobs in coastal cities.

However, dagong zai is generally limited in scope to men, especially those who are poorly educated and lower-paid, holding relatively unstable jobs.

ban zhuan (搬砖): the brick-mover

This online slang term became popular in the early 2010s, and is most often applied to — you guessed it — construction workers. Internet users may appropriate the term when complaining about doing monotonous work for a pittance of a salary.

In an online chat, for example, if someone mentions having to “move some bricks,” they’re saying they need to stop procrastinating and get back to work.

“When I go and move bricks, it means I can’t hold you in my arms,” goes a popular refrain that has been immortalized online for reflecting the dilemma of balancing one’s work and relationships.

shechu (社畜): the corporate cattle

This term, originating from the Japanese word for “salaryman,” caught on in China thanks to the Japanese TV drama “Weakest Beast,” released in 2018.

Shechu resonates with young, urban-dwelling office workers who are less ambitious, and less greedy, than previous generations. They’re also unquestioningly obedient to their bosses in much the same way livestock blindly heed farmers.

One obvious pitfall of this mentality toward work is that it leaves such individuals vulnerable to exploitation.

jiaban gou (加班狗): the overtime dog

This term typically refers to white-collar workers who are consistently forced to work overtime — after hours, on weekends, on holidays, or all of the above.

In the summer of 2016, “My body Is Hollowed Out,” a song produced by an amateur choir in Shanghai, went viral on social media with its catchy rhythms and lyrics. “I’m just as exhausted as a dog,” sing the group’s members, all donning dog-ear headbands, eliciting laughter from the audience.

dagong ren (打工人): the laborer

Dagong ren is a general term for workers who are physically or technically skilled. With making money as their first and only goal, laborers are a resolute group, and would never be caught arriving late to work.

“80% of the pain in my life comes from working, but I know with certainty that if I don’t work, 100% of my pain will come from having no income,” some self-identified laborers, including well-known entertainers, have lamented online. “Working may shave 10 years off my life — but without working, I wouldn’t be able to live for a single day.”

Editor: David Paulk.

(Header image: A screenshot from a “dagong ren” video. From @YY的奇妙冒险 on Bilibili)