Reports of Our Death Are Greatly Exaggerated, Says Chinese Gaming Console

An outpouring of nostalgia flooded Chinese social media Monday following reports that Subor, a much-loved maker of knockoff Nintendo-like consoles from the ’90s, had gone bust. The brand, however, insists that it’s still very much alive — and that netizens have been mourning the wrong company.

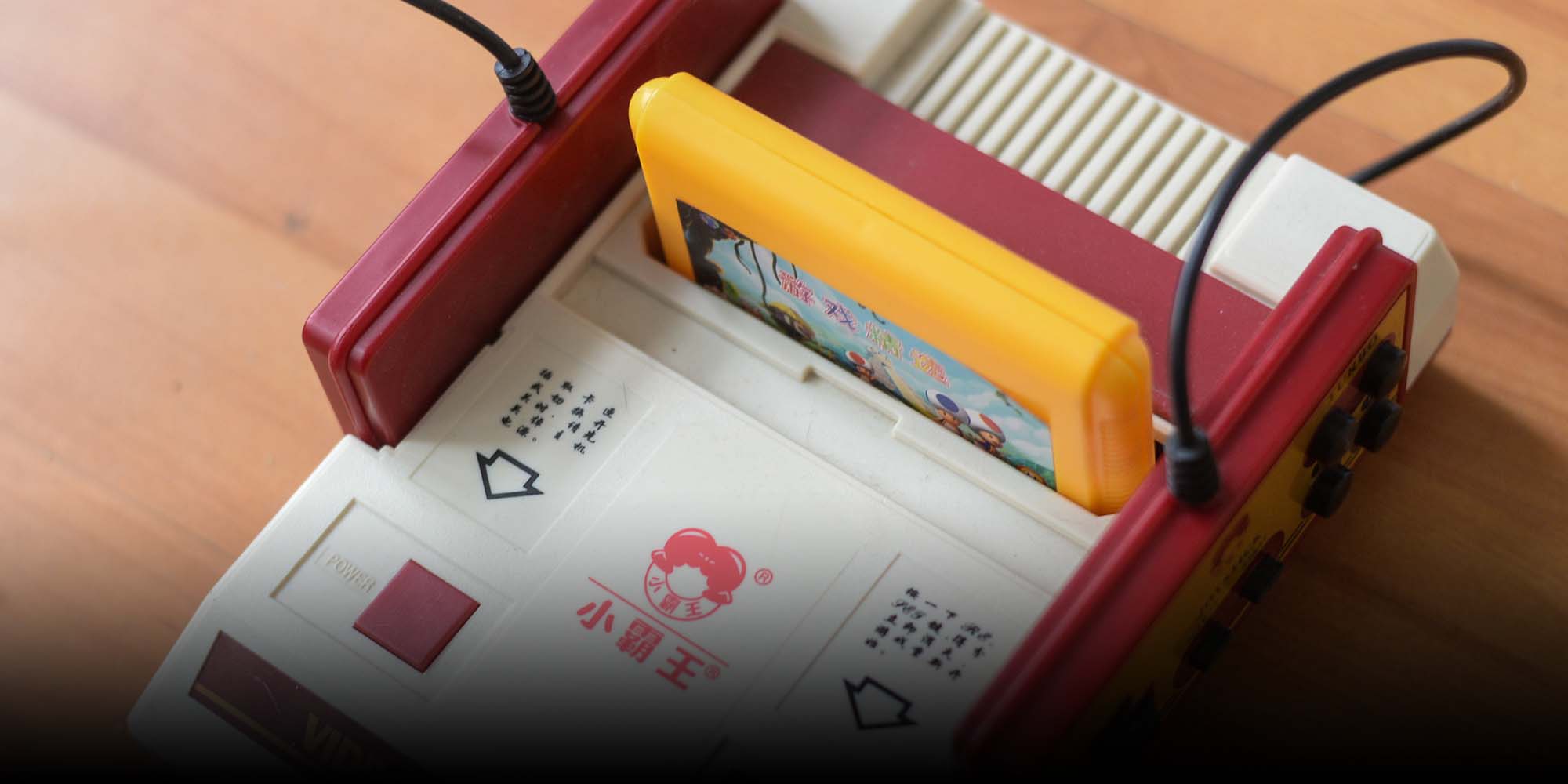

The confusion began Sunday, when The Beijing News reported that a company called Subor Culture Development had filed for bankruptcy, and that its legal representative had been added to a credit blacklist on Nov. 5. The now-inaccessible story described the company as the former manufacturer of the Subor brand of video game consoles — called Xiaobawang, or “Little Tyrant” in Chinese — that were wildly popular in the ’90s.

Dozens of other Chinese media and blogs amplified The Beijing News’ claims, triggering a wave of nostalgia on social platforms. Netizens lamented the apparent demise of the homegrown tech giant, which in its heyday ran prime-time ads featuring martial arts legend Jackie Chan on China’s state-run TV network.

On microblogging platform Weibo, users reminisced about blowing dust out of clunky cartridges for games like Super Mario Bros., Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, and Bomberman, pulling all-nighters to pass nightmarishly difficult levels, and fuming when the cheap consoles would ruin their TV sets.

“Me and my brother once played so much that smoke started coming out of the back of the TV,” a Weibo user wrote Monday under a post about the bankruptcy. “We had to kneel for an hour as punishment.”

WeChat-based media, meanwhile, dug into Subor’s tumultuous past and analyzed what had gone wrong for the company, as well as why China has failed to produce its own rivals to the PlayStation and Xbox.

A day after The Beijing News’ article published, however, Chinese conglomerate Guangdong Yihua Group issued a statement on Subor’s website explaining that reports of the brand’s death had been greatly exaggerated.

Yihua Group, which has owned Subor since 2010, said the console brand still exists, and that Subor Culture Development — the firm that went out of business — was in fact a small company spun off to develop virtual reality products in 2015. During its brief existence, it did not produce a single Subor product.

A media outlet under Tencent News later confirmed that Subor Culture Development was just one of over a dozen companies with “Subor” in their names, and had no ownership of the Subor brand. As such, the console maker is still alive — technically, at least.

In reality, however, a comeback for Subor seems unlikely. Though the outcry over its non-bankruptcy shows how influential the company was in its heyday, China’s Little Tyrant has long been in decline.

The first Subor console was produced in 1987 in the southern province of Guangdong — a manufacturing powerhouse that at the time was fueling China’s emergence as the “world’s factory.” The original Subor was just one of many copycats of the classic 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System, or NES, which remained inaccessible and unaffordable to most people in China.

Subor’s high quality and competitive price made it stand out among the Chinese fakes. Its 200 yuan (then $54) price tag, however, was still more than an urban worker’s average monthly wage.

Many in China had their first taste of gaming through Little Tyrant. Liu Xiaoqing, a 39-year-old documentary director from Shanghai, tells Sixth Tone that after school, he used to go to a “video game room” — an informal, internet café-like business — that offered 30- to 60-minute play sessions on three Subors for just a few cents.

The store became so popular that lines would form outside and people would gather at the windows to spectate. Liu and his schoolmates would often forego snacks and drinks so they’d have some spare change.

“We spent pretty much all our daily pocket money there, or students would treat each other to games: me today, you tomorrow,” says Liu.

In the early ’90s, Subor struggled to convince parents to buy expensive gaming consoles for their kids. But then, in a stroke of marketing genius, the company released the Study Machine.

A bizarre-looking hybrid device with a built-in keyboard, the Study Machine could load programs that taught Chinese, English, computer programming, and music. But — crucially — it also retained the same console gaming functions of previous Subors.

With the help of the Jackie Chan-led advertising campaign and the support of state institutions like the Communist Youth League, the Study Machine generated 800 million yuan in sales in 1995, capturing 80% of China’s console market.

Zheng Yang, a Shanghai-based mechanical engineer, tells Sixth Tone he was one of many adolescents whose parents bought him a Study Machine, believing it was primarily an educational tool rather than a gaming console. “I did use the study functions,” Zheng says. “But when I was allowed on the weekends, I mostly used it for gaming.”

After 1995, however, Subor’s fortunes began to change. The company’s founder, Duan Yongping, left to start a new enterprise, taking many talented staff members with him. Even-cheaper domestic knockoffs of Subor’s copycat products, meanwhile, began to proliferate and eat into the company’s market share.

The Subor consoles also became increasingly outdated, as they weren’t able to run the flashy 3D games available for PlayStation and Nintendo 64.

The hammer blow came in 2000, when Chinese authorities issued a ban on the sale and manufacture of gaming consoles, which it considered addictive and harmful to children. The ban wouldn’t be reversed for another 15 years, and ended up making PCs — and later mobile devices — the top gaming platforms in China.

In recent years, Subor has established a slew of subsidiaries and attempted to reinvent itself as a maker of household appliances, speakers, cellphones, and VR systems. These subsidiaries evolved into independent spinoff companies that pay Yihua Group for the rights to use the Subor name.

In 2018, one Shanghai-based Subor subsidiary launched an original Microsoft Windows-based console in partnership with U.S. chipmaker AMD — the first time the Chinese brand had returned to its gaming roots in nearly two decades. Despite generating some hype, the product failed to attract many buyers due in part to its high cost, and the subsidiary ultimately folded last year.

Though many netizens still have affection for Subor, its legacy in China is disputed. For some, there’s little to celebrate about a company known mainly for creating pirated copies of a Nintendo device. “It’s just a knockoff,” one unsympathetic Weibo user commented. “If it’s gone, it’s gone.”

Zheng, the engineer, echoes this sentiment, saying piracy is fundamentally wrong. At the same time, he points out that Subor was still an important conduit linking Chinese people and video games at a time when most were too poor to access the real thing. “Kids back then didn’t understand intellectual property rights,” says Zheng. “It was because of this console that we were able to play these games at a fairly low price.”

For Yu Yang, a U.S.-based accountant who played Subor growing up in China, Little Tyrant may even have laid the foundations for today’s vast Chinese gaming market. “Because these games were a very scarce form of entertainment, many people grew up with a deep love of them,” Yu tells Sixth Tone. “It’s because of this that many people in their 20s and 30s are so willing to spend money to fulfill their childhood dreams.”

“If there had never been a Subor, China’s gaming industry today might look very different,” Yu says.

Editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: A photo of Subor’s “Little Tyrant” gaming console, a knockoff of the Nintendo Entertainment System that was wildly popular in China in the 1990s. IC)