A Song of Eyes and Fire: Battling the Blaze, Freezing Time

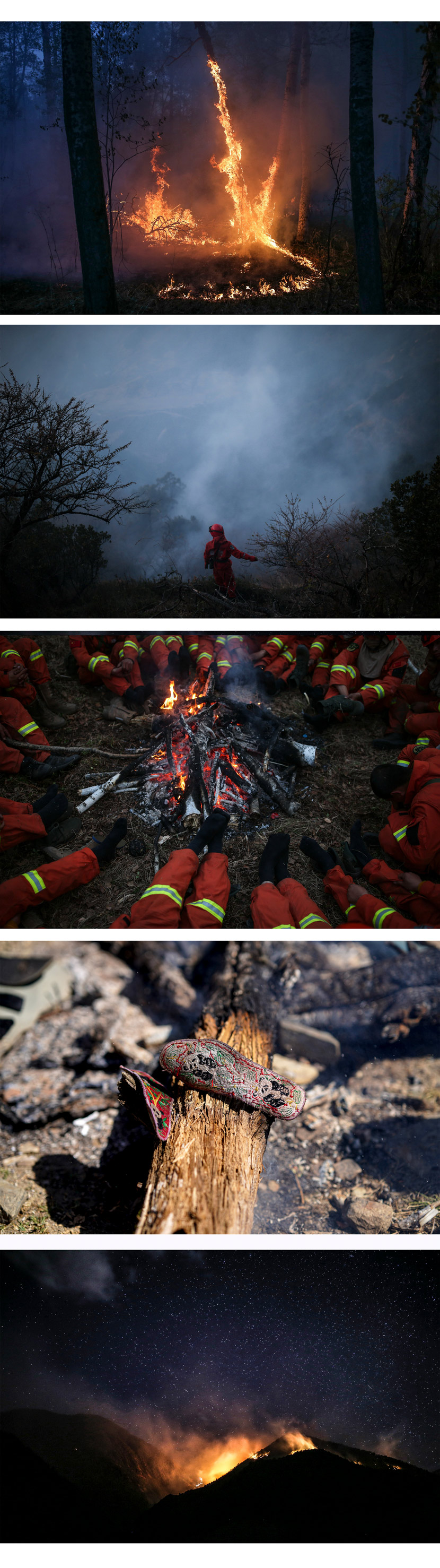

SICHUAN, Southwest China — When 27 firefighters were killed battling a wildfire in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture in Southwest China’s Sichuan province on March 30, 2019, Cheng Xueli was on the front lines. He was there again exactly a year later when a second blaze claimed the lives of another 19 comrades.

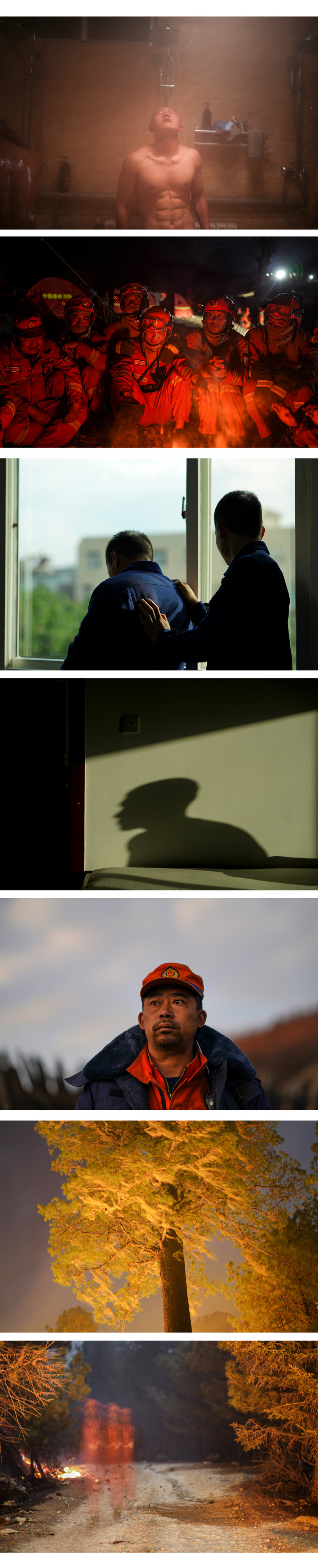

Through it all, Cheng led two lives. As he fought the inferno as part of the State Firefighting Service of the Ministry of Emergency Management in Sichuan, Cheng also photographed their gargantuan efforts and sacrifices. His images beaming across local and national media captivated China — from a smoke-filled countryside to a mountain ablaze, and from camaraderie and heartbreaking loss among the first responders to their mundane daily lives.

But Cheng found it harder than usual to control his emotions after selecting the best photographs of his unit’s most recent firefighting effort — a third wildfire in May this year in Liangshan that saw no casualties. It was also Cheng’s 129th operation since joining the force 13 years ago.

Hesitating for a moment, he says he’s unsure whether he’s spent a significant amount of time simply dealing with the emotions of putting out the fires or if his memories have just made it unclear. Cheng tells Sixth Tone, “Obviously, after working as a firefighter on the front lines for 13 years, I am very different from when I joined the force.”

For him, trying to describe a fire he’s fought and emphasize its danger is incomplete and vague. It’s why he prefers photography. “It (photography) seems more benevolent,” he says, adding that photography can also offer a wider sense of space to comprehend the profession.

Cheng understood this following the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan province in his second year in the Armed Police Forest Force, then under the People’s Armed Police (PAP). That tragedy claimed nearly 70,000 lives, and Cheng couldn’t rescue anyone living. As a soldier, he thought he’d be able to save people from suffering. “Sometimes, you just can’t,” says Cheng.

Soon after, he bought a point-and-shoot camera to document himself and the people around him. Then, Cheng says, he was a complete novice at photography, but he did it anyway just to make himself feel better — which he did every time he pressed the shutter. “But you just can’t (save people all the time), and that’s just it,” he says.

But taking photographs did give Cheng a sense of calm. Slowly, he began to photograph his colleagues, his life in the PAP, and the ordinary days outside disaster areas, such as training, mountain patrols, and even happy or embarrassing moments. “Taking pictures makes me feel that disasters are just one part of life,” he says.

Before Cheng became a member of the Armed Police Forest Force, he wanted to be a commando but in his hometown, Jianshui, a small town in the southwestern Yunnan province, the only choice for him was the Forest Force.

Cheng fondly recalls the day he joined the Forest Force. Nearly every household in town set off firecrackers to see off the recruits, who were all given a big red flower to pin on their chests. Soon after, Cheng advanced quickly, working hard to become his team’s squad leader, even receiving awards for his excellent work during important rescues.

But it still didn’t feel right. “Perhaps I felt the social status of firefighters was low compared with other soldiers,” Cheng told Sixth Tone. “To be honest, despite the profound brotherhood and sense of identity, I still felt I had no sense of belonging, and I didn’t even want to post pictures of myself wearing a firefighting suit to friends on (messaging app) WeChat.”

But Cheng stayed on and got his break while updating his photograph on his ID card, a mundane chore. Then, he recalls, the cameraman muttered that he needed to adjust the camera’s aperture and shutter. Cheng responded, “What’s an aperture and shutter?”

The professional explained it to him. And that was the first time Cheng understood what it took to use a professional camera and what the job actually entailed. His curiosity led him to buy a better camera and soon, Cheng’s work was published by People’s Daily, the country’s largest circulated daily, and the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China.

This motivated Cheng to photograph more. Soon, a leader from his unit suggested he stay and become a journalist for the Forest Force. Cheng quickly agreed. “I felt like I was embraced by photography back then,” he says.

In 2012, Cheng shifted focus from actual firefighting to documenting his unit’s arduous work. But it wasn’t easy to separate the firefighter from the photographer. Cheng says he’s managed to do both even now, after officially retiring from his unit and joining the journalist unit.

He still couldn’t help but put down his camera and pick up a fire hose instead. “For me, I’m a firefighter first, from the bottom of my heart.”

Cheng basked in the new role and kept it going for a few years. He mastered more skills, particularly those required to capture tension and those “decisive moments” highlighting the efforts of soldiers operating during disasters.

During a random exchange of ideas in 2014, a photographer he met in a village in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture critiqued Cheng’s work and recommended he read more about big news agencies like Magnum Photos.

A year later, Zheng Pingping, the photo editor of China Youth Daily spoke to Cheng, saying, “Could you send me some photos not from the field? The ones of those ordinary moments with you and your colleagues’ daily lives.”

He complied, and Zheng published a photo essay. “Zheng’s creative ideas changed my life as a photographer,” says Cheng.

The photo essay was an instant success and was soon also published by other media outlets, garnering more attention for Cheng’s work and the firefighters he sought to highlight. More photographers soon began contacting Cheng to share ideas and expand the boundaries of his work.

When more assignments followed, Cheng was pleased, but also saw it as an opportunity and responsibility to ensure more visibility for his comrades in the public eye, as well as better understanding and respect for his profession.

That changed after the Liangshan wildfires killed 46 firefighters in the span of one year. Cheng refused nearly all requests, and like many other colleagues, suffered post-traumatic stress disorder.

It was cruel for Cheng. As a journalist, Cheng also had to encourage himself to try and focus on selecting photographs of the tragedy. But every time he looked at the images — the shadow of a gutted tree, the light of the fire, or the blurred firefighters amid charred forests — it almost always drew him back to tragic memories, making it hard for Cheng to continue. Breaking down, he says, “It hurts. It is really, really painful.”

Cheng is still trying to find a way to manage his emotions. There were even times when he thought of giving up photography and leaving it behind, but his colleagues and their families kept encouraging him to continue, at least as a way to commemorate the fallen comrades. And sometimes, photography was the only way to get through the grief.

“Now, I will try my best to observe and press the shutter, to keep alive the memories of being among the clouds, mountains, forests, or fires, as well as the other soldiers. I can only keep going to fight, to chase, to recall, to confirm things by taking photos,” he says. “But some things take time.”

(Header image: A firefighter rests in flowering shrubs in Sichuan province, April 2020. Cheng Xueli for Sixth Tone)

Correction: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the fires took place in Muli Tibetan Autonomous County, whereas they occurred in multiple locations in the surrounding Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture. The article has since been adjusted.