A Woman Called ‘Hey’

This story is part of a weekend column featuring translations from respected Chinese media outlets, as selected and edited by Sixth Tone. All are reproduced with the outlets’ permission. A version of this article was first published in Guyu Lab.

GUIZHOU, Southwest China — For as long as Li Xinmei can remember, her mother has been someone with no name.

Li’s father usually just called her “hey,” and neighbors would simply tap her on the shoulder to get her attention. On her ID card, her mother’s name is Li Yurong, and her date of birth is July 15, 1960 — both of which Li Xinmei’s father arbitrarily made up.

There were more things that didn’t make sense. Li Xinmei remembers her mother keeping a knife beneath her pillow, always with the handle facing out and the blade facing in. As an adult, Li Xinmei would purposely take it away, but it wasn’t long before a new knife would appear under the pillow. And so it went for more than 30 years. Her mother never used the knife but for some reason insisted on sleeping with one.

Only this year, when Li Xinmei finally discovered her mother’s true identity did someone explain to her that the pillow knife is a custom of the Bouyei ethnicity, a minority group that lives mostly in Guizhou province, some 900 kilometers southwest from their village Zaosheng in central China’s Henan province. The knife, Li Xinmei learned, keeps nightmares at bay. And what her mother went through would disturb anyone’s sleep.

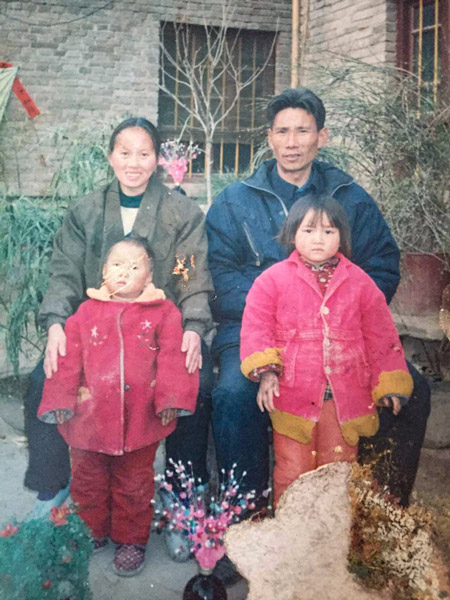

In a winter 35 years ago, Li Xinmei’s mother was abducted by human traffickers from the train station of Chongqing, a city neighboring Guizhou. She was taken to Zaosheng and sold to Li Xinmei’s aunt, who meant for her to become the wife of Li Xinmei’s father, Li Wei. He thought the short and dark-skinned woman was ugly. Her abductors had beaten her, and she was missing several teeth. Her ears were bleeding, which, Li Wei figured, explained why she had poor hearing. He didn’t want to marry her, but eventually gave in to his sister’s insistence. Li Xinmei’s mother had become one of the many women who have been trafficked across or into China to be forced into marriages.

Li Xinmei doesn’t know whether her mother has many nightmares, because she can only have the most basic conversations with her. Her mother speaks a language that appears entirely dissimilar from the Chinese spoken in Henan, one that nobody in their village can understand. Even Li Xinmei, having grown up hearing her mother speak, can only comprehend about half of what she says, having never learned to speak the language herself. Her mother’s poor hearing, meanwhile, means she never learned to speak Chinese. She can write just two crooked Chinese characters that Li Xinmei taught her: Zaosheng, the name of their village. “At least she should be able to tell people where her home is,” Li Xinmei says.

Her mother, however, does not feel like Zaosheng is her home. Li Xinmei remembers that from the time she was a child, her mother would repeat two puzzling words that sounded like the Chinese for “smoke” and “white smoke.” Only later did Li Xinmei understand that she was saying “home” and “return home” in her own language.

Li Xinmei would sometimes ask, through gestures, where home was. Her mother’s reply would invariably be indecipherable. But she would often say to Li Xinmei and her younger sister, “Let’s go home. It’s beautiful there.” In her mother’s memory, there was a large waterfall near her old home that she used to pass, with fat plantain trees growing in front of the house and a tall chestnut tree her father would shake when the chestnuts were ripe enough to take to the market and sell.

Rediscovering that place long seemed a near-impossible wish to fulfill. No one knew who she was. Li Xinmei’s mother has a face unlike those around her, with high brow bones and deep-set eyes, leading some in the village to surmise she must be a foreigner.

Beginning in 2010, Li Xinmei tried to help her mother search for her home, joining groups on chat app QQ dedicated to looking for lost relatives. Having been told by her aunt that her mother had been kidnapped from Chongqing, Li Xinmei focused on that area. But nobody ever recognized the snippets of her mother’s speech she would share. Similarly, websites for missing people never produced valuable leads as her mother remembered little about her own past. Li Xinmei sometimes received replies online from people claiming her mother might be from Sichuan province, which borders Chongqing, or even Vietnam.

Meanwhile, with her mother now about 60 years old, Li Xinmei figured her grandparents probably wouldn’t be alive anymore, so who would remember her? After a few years, she gave up looking.

Running Away

Li Xinmei’s mother had attempted escape twice. The first time was shortly after arriving in Henan, when she ran away carrying two pairs of small shoes she had made. But the escape lasted only two hours before her new “relatives” found her. Li Xinmei said that they deduced from those two pairs of shoes and things her mother said that she might have given birth to a child before she was brought to Henan, somehow losing them. “Probably also trafficked,” Li Xinmei says.

The memory of a lost child is something Li Xinmei’s mother carries with her at all times. Last year, an insurance representative came to their home so Li Xinmei could sign her son up for health insurance. While signing paperwork, her mother suddenly became agitated, hugging her grandchild and pushing the representative out the door. “She thought I was selling my child,” Li Xinmei says.

The second escape attempt was during her ninth year in Zaosheng Village, when she left with 4-year-old Li Xinmei and her 2-year-old sister. To this day, Li Xinmei still remembers it: Her mother came to pick her and her sister up from their grandmother’s house, saying as she dressed them in thick clothes, “Let’s go. Let’s go home. This is not our home.” She had taken her ID card and some money. They slept at night in a haystack and walked throughout the day. Two days later, when they finally reached the county train station, they were met by people from Zaosheng. They had been waiting for her.

She apparently gave up and never ran away again, staying to live with Li Wei. In Li Xinmei’s account, he was an honest man, and they worked together in the fields. The few Chinese words that her mother could understand were mostly related to labor: pot, rice, wheat, seed, fertilizer. If Li Wei mentioned these words, she would do the corresponding work. The house was quiet most of the time, with the couple watching TV: “There wasn’t much communication, but they wouldn’t have had much to say,” Li Xinmei says.

In their village of more than 4,000 families, her mother was a curiosity. The women in the village often sat together to shell peanuts, and when they talked, her mother watched and listened carefully. Li Xinmei feels that “she pretended to listen, because she felt she had to fit in.” When others laughed, she laughed as well. “Sometimes when people were laughing at her, she thought they were telling her a joke,” Li Xinmei says.

As Li Xinmei grew up, she gradually realized that her mother was different. When her mother sent her to school, her appearance made classmates stare: “Look, Li Xinmei’s mother is so ugly.” She avoided being seen with her mother. If she was walking with classmates after school and saw her mother coming, she would turn her head and walk straight home. “You feel terrible that others have normal mothers they can talk to and do things with, whereas you don’t,” Li Xinmei says.

Her mother is very diligent and can make exquisite cloth items. She made Li Xinmei nice-looking shoes and a little book bag, embroidered with colorful designs different from those in Henan. When Li Xinmei carried the bag to school, some students envied her for having such a unique bag, but she hated being different. She eventually gave it to a classmate.

In fifth grade, Li Xinmei realized that other children had two sets of grandparents. Other people would ask about her maternal grandmother and whether she’d gone and visited her. She thinks that from that time, she started secretly hoping her mother would find her home: “I really wanted to have a maternal grandmother who would be from a different ethnicity, or foreign — somewhere where people wouldn’t look down on us, where we’d have a family.”

In late 2017, her father Li Wei was diagnosed with esophageal cancer and was hospitalized for three months, to no avail. When his body was returned to them, as if in disbelief, her mother went up and nudged Li Wei’s arm. Then she cried.

As far as Li Xinmei could remember, her mother had never before cried for Li Wei. In Li Xinmei’s words, “It’s a relationship like a roommate, but after a long time, people have feelings. It’s not even a relationship: It’s family.”

The day after her father’s funeral, the family was eating at the table when her mother said to herself, “Your father’s dead, and I’m ready to go. I’m going home, but you two can stay.” Still, that was easier said than done.

Bixnuangx, Come Home

In September of this year, Li Xinmei was randomly swiping through a short-video app when she came upon a video about the Bouyei language. It sounded very familiar, and she recognized certain words her mother would use. She contacted the vlogger and described her mother’s situation. She wondered whether he could tell whether her mother’s language was Bouyei.

The vlogger, Huang Defeng, is a member of the Bouyei ethnicity and a civil servant in the tax bureau of Anlong County, in Guizhou’s Qianxinan Bouyei and Miao Autonomous Prefecture. Reserved and well-spoken, he enjoys making instructional videos to promote the Bouyei language. He explains that the Bouyei people number approximately 3 million, 97% of whom live in Guizhou. Born in 1992, he says his generation still speaks the Bouyei language, but many children of the next generation do not: “Many people might have an inferiority complex about their native language and feel that speaking it is a sign of backwardness, so the younger generation’s parents, who are born in the 1990s, are reluctant to pass on our native language to the next generation.”

Huang remembers that, in the evening of Sept. 10, Li Xinmei sent him two voice messages of Li Xinmei’s mother talking about going home, saying in tears, “The child can’t be found, where did the child go?”

Li Xinmei remembers the crying started because her own son had accidentally sat on the family shrine. This was a cardinal sin to her mother, who considered the act blasphemy. She kept on crying and kept on talking. “She probably felt that her lost child could never be found again, so I felt especially sorry for my mother,” Li Xinmei says, recalling the scene and welling up.

Huang was certain the first second he heard the recording that it was the Bouyei language. Despite having been away from home for a long time, the old woman’s pronunciation hadn’t changed, and her vocabulary was very authentic. Huang asked Li Xinmei to send a picture of her mother. “As soon as I saw what she looked like, I was 100% sure she was a Bouyei,” Huang says.

He excitedly told Li Xinmei what he thought, and Li Xinmei expressed her gratitude. But it was hard to be happy or hopeful. What could she do even if she was sure her mother was Bouyei? With millions of people in the Bouyei ethnicity, how could she find her mother’s ancestral village?

Huang was more optimistic. Sleepless that night, he made a short video of the woman’s voice, forwarding it to many Bouyei people. Their language can roughly be divided into three dialects found in southern, central, and western Guizhou. Huang wasn’t sure exactly which version of Bouyei the woman was speaking and asked for help identifying it. Zhou Guomao, an expert on Bouyei culture, determined that Li Xinmei’s mother probably grew up in western Guizhou.

At noon the next day, Li Xinmei found herself in a chat group called “Bixnuangx, Come Home” — using the Bouyei word for compatriot. At the initiative of Wang Zhengzhi, a friend of Huang and a Bouyei translator at the Qianxinan Radio and Television Station, it filled up with people from western Guizhou. Li Xinmei watched the chat swell to 40 members.

Within 10 minutes, someone said that the accent belonged to either Pu’an County or Qinglong County. Some people in the group suggested making a video call to Li Xinmei’s mother, but she still appeared upset from the shrine incident, and, potentially due to her bad hearing, didn’t react much to anything being said.

The situation was at an impasse. Qinglong and Pu’an are neighboring counties with a combined population of nearly 600,000 people, so finding the true identity of a woman who was trafficked 35 years ago was still like searching for a needle in a haystack. Later on, the group had a new idea. People from Pu’an and Qinglong sent pictures of the typical dress, scenery, and customs of the local people to Li Xinmei, so she could show them to her mother.

This approach proved effective, and her mother made out a waterfall, saying, “From here, you can go up the slope to Qinglong County.” She also recognized a winding road. Built in 1936, it snakes up a mountainside in 24 bends and is locally famous. Her mother pointed to a picture of it and said, “There’s a temple here, a house there, and down the road is Dezyians’ house.” (Bouyei people use single-syllable names, with “Dez” a common prefix. Bouyei who have undergone more formal education now commonly adopt Chinese names).

Wang, the translator, tells Guyu Lab that when they did some research and were unable to find a temple or house near the 24-turn road, they were deflated, and thought the woman may have misremembered. But Cen Guanchang, who works at the Qinglong County Statistics Bureau, knew the local situation better. After getting off work late, he looked through the chat and told everyone that the woman was right: There had indeed been a temple next to the 24-turn road but it had been demolished decades ago during the Cultural Revolution. It must mean Li Xinmei’s mother came from a nearby town.

In less than a day, the search had narrowed down considerably. The group was excited, but Li Xinmei’s mother did not react to any of their other photos. By the morning of the 13th, more than a full day later, there had been no progress, and the earlier enthusiasm ebbed.

“I am Liangz”

But the breakthrough would come just a few hours later.

Luo Qili, a Bouyei woman who runs an ethnic clothing business in Pu’an County, is a warm and cheerful person who often travels around the neighboring towns and villages, making a wide range of friends. After carefully watching the video of the old woman’s reaction to the waterfall and the 24-turn road, she noticed two words the woman said: “Bollings” and “Ndaelndongl.” Others thought they meant “steep slope” and “forest,” but Luo thought the words sounded somewhat like the names of two villages near Shazi Town, a place close to the mountain road.

Luo immediately called around and reached a friend who was at the Shazi Town market. She asked her friend to inquire elderly passersby if they were from either of those two villages, and if there were any women who had been abducted from those villages.

At 2 p.m., the friend called back. An old man said that more than 30 years ago, in a nearby village called Bulujiao, a woman named Dezlinz had gone missing. She was the right age to be Li Xinmei’s mother.

Everyone in the group was so excited that someone immediately taught Li Xinmei the pronunciation of Dezlinz, so that she could try to shout to her mother, “Dezlinz!” But her mother shook her head, saying “I’m not Dezlinz, Dezlinz is from Bulujiao.” Everyone was disappointed, but, quickly, realized her knowing Dezlinz must mean she grew up close to Bulujiao.

A couple of hours later, Luo’s friend had more news. Another elderly man at the market said that more than 30 years ago, a woman named Dezliangz from his own village had been trafficked. She had a father named Dezdins, three younger brothers, and a younger sister.

Li Xinmei shouted to her mother again, “Dezliangz! Dezliangz!” After 35 long, nameless years, it was the first time Dezliangz had heard her name called out. The smile on her face grew a little wider, and with a little shyness, she said with some hesitation, “You know my name? Xinmei, I am Liangz.”

Reconnecting

Luo then found out that Dezliangz’s father, 88, and mother, 84, were still alive and well, and she pulled Dezliangz’s brother into the group. Shown a picture of Dezliangz when she was younger, he confirmed she was his missing sister.

The next day at noon, Dezliangz’s brother, Dezzuany, set up a video call between his long-lost sister and her parents. What Dezliangz saw were two withered old people, the mother wearing the dark blue headscarf of the Bouyei ethnicity. After taking a moment to make sure it was her, Dezliangz called out, “Mom!” The two elderly people began to wipe away tears. Dezliangz could not hear what they said, and asked, “Are you crying? You cried when I disappeared, didn’t you? Did you look everywhere for me?”

Li Xinmei cried.

Up until the video call’s confirmation, Li Xinmei couldn’t stop wondering whether it was all a hoax. How could this group of strangers have found her mother’s hometown in two and a half days when she couldn’t find it during her previous years of searching?

When Li Xinmei told a neighbor, their immediate response was, “How much did it cost?” She said she didn’t spend any money, but the neighbor didn’t believe her. A friend was equally incredulous, and even contacted Huang to ask in a roundabout way whether he had any ulterior motives. Huang, slightly exasperated, had to explain to Li Xinmei that he and others were all people in state employment and wouldn’t charge her a penny. He stopped Li Xinmei from sending a digital payment red envelope into the chat group. “From the beginning to the end, to now, I feel like I haven’t done much,” Li Xinmei says. “The most I did was record a few videos of my mother for them. They did all the research, and all the legwork.”

Huang explained their goodwill by saying that because of the smaller population, the bonds between the Bouyei people are strong. Another reason may be empathy for people with similar experiences, as many in the group could tell stories of women in their family who were trafficked and sold. Luo and Wang both have cousins who went missing. Another group member, Luo Qian — unrelated to Luo Qili — has an aunt who disappeared. Some relatives were found, but most were not, leaving huge holes in their families. Luo Qian says that before the migrant labor boom in the 1990s when people leaving their villages became common, Bouyei women were common trafficking targets because the language barrier made it difficult for them to find their way home.

Dezliangz’s sister says Dezliangz was trafficked when her younger siblings were very young. Her parents were simple people: The family was so poor that it was difficult to get even a steamed bun to eat, and her mother would have to hide it and give it to the youngest child first. “He (the trafficker) just thought we were easy to pick on,” she says. “Had we been grown up, he wouldn’t have dared.”

Dezliangz’s story spread locally, and Luo Qili says that a group of people in a nearby town followed their example and helped a Bouyei person in the eastern Shandong province find her home.

Wang says she later learned that Dezliangz’s ears were not injured by the traffickers, but rather that she was born with weak hearing and learning difficulties. Before she was trafficked, she married into a neighboring village but was not accepted by her husband’s family, who acquiesced to three traffickers taking her away. Two weeks later, Dezliangz’s father discovered his daughter was missing and went to the traffickers’ house with a knife, where they pleaded with him, saying they would definitely return Dezliangz. But they never did.

Going Home

On Sept. 14, after the video chat with her parents, Dezliangz did not sleep all night. She said to Li Xinmei: “They’re still alive! Still around! Let’s get a tractor and go.” Li Xinmei told her mother that they would have to go after the fall harvest. She then booked a ticket for Oct. 17 to fly to Guizhou. It was as if Dezliangz understood, and as if she didn’t. She didn’t know who had helped find her parents, thinking it was Li Xinmei who located them from searching on the phone. As soon as she saw Li Xinmei making a phone call, she just stared. She would no longer allow her grandson to play with the iPad — with the picture of the 24-turn road saved in it, she was afraid it would run out of battery.

Finally the day came to go to the airport. They took a three-wheeled motorcycle, a taxi, and a bus, stayed overnight in a hotel near the airport, and then caught the two-and-a-half-hour flight the following day. They landed and were greeted by Wang, Huang, Luo Qian, and others, who were waiting with flowers and banners. Media was present, too. Wang remembers that everyone was very excited and a few volunteers even shed tears, but Dezliangz, who was the center of attention, looked calm — showing some disappointment and even anger.

Only Li Xinmei understood her mother’s feelings. “She started to look forward to it, thinking that the end of every leg of the trip would be when she arrived home. But each time, it wasn’t.” Every transfer, Dezliangz looked angrier and angrier, to the point where she didn’t even look Li Xinmei in the eye. “She probably thought I had been lying to her.”

On the road from the airport to Qinglong, Dezliangz looked like she was in a bad mood, and when Wang tried talking to her as she drove, Dezliangz ignored her. She repeated: “Why are we going so far? Where are you taking me?” After getting out of the car, Dezliangz sat on the side of the road, carsick and upset.

Then, suddenly, a group of people arrived, most of them wearing brand-new traditional clothes of a kind Bouyei people wear for important occasions. The only exception was an elderly woman wearing old clothes, wrapped in a gray headscarf. Just 120 centimeters tall, she was withered, thin, and old. She slowly walked up to Dezliangz, holding a bowl of white rice. With a pair of chopsticks, she held some rice to Dezliangz’s mouth for her to eat.

It was Dezliangz’s 84-year-old mother. According to Bouyei custom, when you return from a trip, you must have a bite of hot rice at home — so you won’t get lost again. As if she hadn’t realized what was happening, Dezliangz held her mother’s hand as she tried to take a bite, but she still didn’t eat.

For the onlookers, it was an emotional scene. Many shed tears, and Dezliangz’s brother, Dezzuany, became red-eyed and turned away.

Dezliangz helped her mom back into her house, turned around, and smiled her first smile of the trip to Wang. “She didn’t realize until then that I was taking her home,” Wang says. Inside the resettlement house that Dezzuany had recently been allocated as part of China’s poverty-alleviation campaign, the reunited family sat on the sofa for an hour, Dezliangz’s mother and father holding her hands. They had much to talk about. Her mother’s sad eyes never left Dezliangz.

Li Xinmei shared a video on her social media WeChat feed that night of her family eating together. Huang, Wang, Luo Qili, and others sang a Bouyei folk song, “The Guest Welcoming Song.” One friend left a message for Li Xinmei: “You have such a big family after all.” Li Xinmei says that when she saw this, she wanted to cry: “I felt so happy.”

Belonging

For Dezliangz, everything was different. The original houses were gone, as were the plantain and chestnut trees in front of the house.

The family had changed in every way, except that they were still poor. Their house was in disrepair and sparsely furnished. Her parents’ bedroom had only a bed and a near-empty wardrobe. Her father’s clothes were piled on the bed, looking like they hadn’t been washed in a long time. The most valuable thing in the house was a square, heated table that could warm up both food and diners. The kitchen stove was covered with a thick layer of dust.

Her parents were elderly and frail, with Dezliangz old and gray-haired herself. But it was as if she had suddenly become a daughter in her 20s again. There, she became very busy, cleaning the house and cooking for her parents. She washed her father’s soiled coat and pants, took the bed sheets out to sun them, and put on a clean cover. She fed the chickens and dogs in the yard. She even planted some cabbages for the neighbors.

Li Xinmei couldn’t help but notice the change in her mother, who was suddenly smiling all the time. When Dezliangz told her parents funny stories about Li Xinmei growing up, her tone was even a little bit sassy. There, Dezliangz had plenty of people to talk to, and Li Xinmei saw her one day holding hands with a neighbor, laughing, and chatting as they walked, talking so much that they didn’t even see her daughter standing by the side of the road. “She was back in her own world, and was no longer some curiosity.” According to Li Xinmei, her mother’s most uttered phrase became: “I’m not going to leave, but you can if you want to.”

But her wish was destined to be unfulfilled, as the family seemed incapable of taking in a daughter who had suddenly returned. Her parents had no income, and her second brother and his wife worked far away, earning meager salaries. Her younger brother, Dezzuany, barely made ends meet working odd jobs to support four children.

Li Xinmei did not want her mother to stay. She bought tickets back to Henan for Oct. 30, making it a short, 12-day reunion. She asked her uncle Dezzuany to talk to her mother: “Tell her that this is not her home; it’s her brother’s home, and she can’t live here because when all five children return home there won’t be enough space. She doesn’t even realize that this place doesn’t belong to her anymore, that her home is in Henan.”

But Dezzuany didn’t need to say anything, because the trip up the mountain to pick up her mother went smoother than Li Xinmei expected. She showed Dezliangz a video of her grandson and told her she would take her again for the New Year. Dezliangz didn’t say much, but meekly went to get her bag, looking calm but still shedding tears as she stuffed her clothes inside. The eyes of her octogenarian mother were red as well.

After the big reunion, Dezliangz still had to return to a world where no one listened and she could talk only to herself. While waiting for the bus at Dezzuany’s house, Li Xinmei was talking with a friend and Dezzuany was looking at his phone. Dezliangz looked at them and said something, but no one responded, so she turned her head and watched TV. She didn’t know how to use the remote control, and she didn’t know how to enlarge the preview screen on the TV, so she had to stare at that small screen the whole time.

There was something in her that had been destroyed, and returning home didn’t get it back. She couldn’t even find out how old she was, as her parents had long forgotten the exact age of their daughter when she was trafficked. At Dezzuany’s house, Dezliangz would still talk to herself, saying, “I lost the food … I lost the child.” Though that was many years ago, she seems not to have moved forward, and to live in her own time and trauma.

If anything has changed, it may be that Dezliangz finally has something to look forward to in her life. Before she left, she met up with her old neighbors and told them, “I’ll go back to take care of the children, and when the New Year comes I’ll steam some buns and come back.”

Li Wei is a pseudonym.

Translator: Matt Turner; editors: Yang Xiaozhou and Kevin Schoenmakers.

(Header image: Dezliangz poses for a photo in Qinglong County, Guizhou province, Oct. 28, 2020. Stephen Che/Guyu)