English, Sex, McDonald’s: The Artist Capturing China’s Go-Go Years

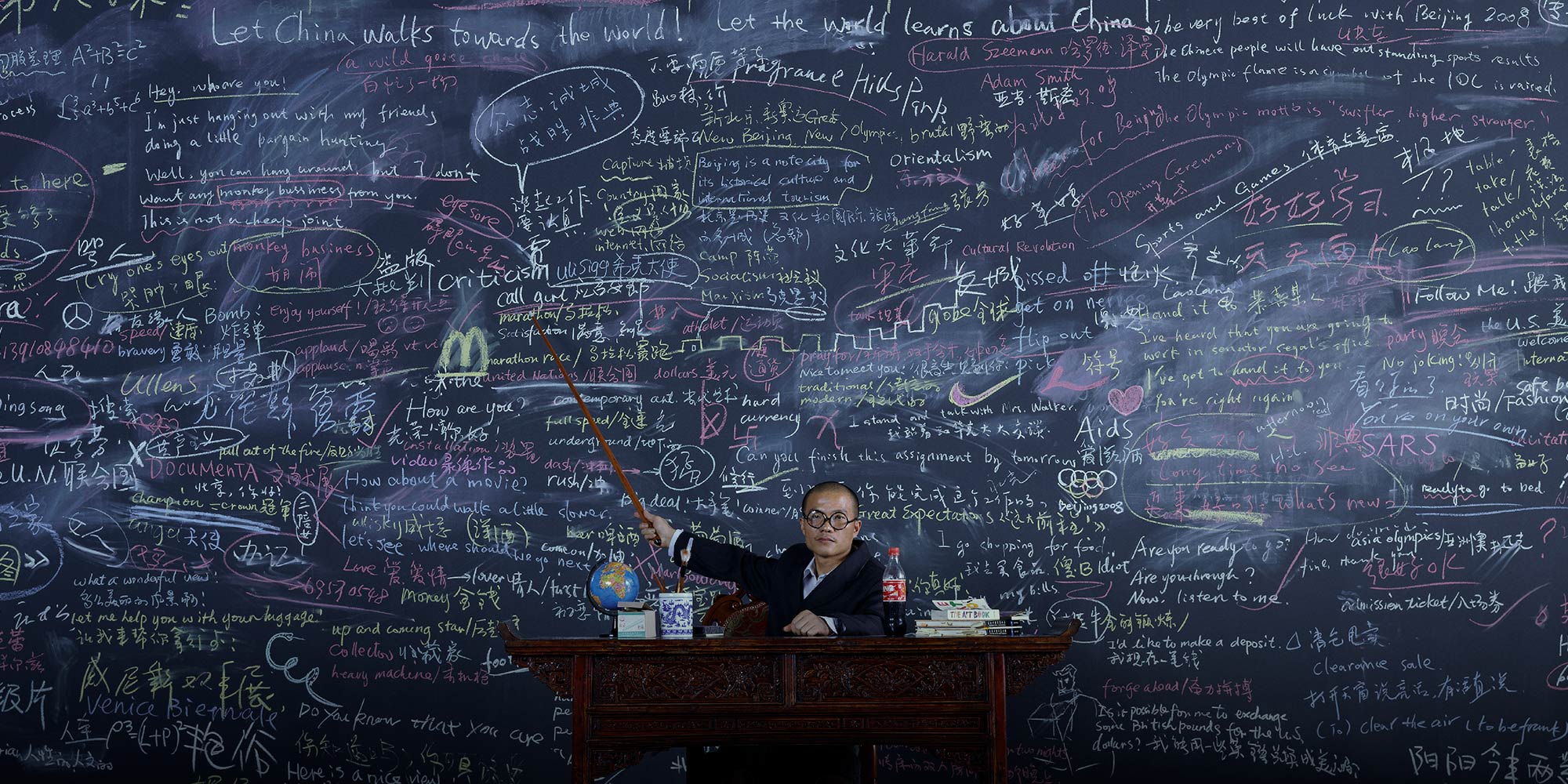

A professor sits behind a battered wooden desk at the front of a lecture hall, pointing earnestly at a giant blackboard filled with gibberish.

Across the top, the subject of the lesson is scrawled in broken English: “Let China knows about the world! Let the world knows about China!” The space below is crammed with corporate logos, propaganda slogans, and random English buzzwords: “Adam Smith,” “AIDS,” and “Orientalism” sit next to “Great Olympics” and a Nike swoosh.

The academic, for some reason, is using a pool cue to draw the class’s attention to the phrase “call girl.”

The surreal scene was created by Wang Qingsong, an artist who specializes in exposing the pathologies of modern China through gargantuan staged photographs.

Born in 1966, Wang’s early life was marked by social upheaval. As a child, he lived through the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Then, he witnessed China undertake a dramatic series of reforms that transformed the country into a globalized market economy.

After decades of Maoist austerity, China’s leaders began preaching a new gospel, opening the doors to Western corporations and extolling the virtues of wealth. For many, it was an exciting, but also unsettling period.

“Marketization not only changed our lives, from poverty to affluence; it also changed our values, our traditional culture, and everything,” Wang tells Sixth Tone. “It reinforced everyone’s desire and greed.”

Much of Wang’s career has been spent grappling with the legacy of this turbulent era. His childhood under Maoism gave him an unusual perspective on the new China that was emerging, allowing him to see clearly its contradictions.

“Regarding the development of a society, you can’t say it’s right or wrong,” says Wang. “But I have to ask questions.”

He began creating oversized installations that embodied the social neuroses he saw around him. These massive tableaux — which often take weeks to build — allow him to take an issue and blow it up to an extreme, exposing its absurdity.

“I always emphasize that (my work) is a kind of documentary,” says Wang. “We live in such a special and complex country, where so many joys and sorrows occur every day.”

The work featuring the professor and his bizarre blackboard — titled “Follow Me” — is a classic example of this approach. It captures the frenzied, breathless nature of China’s embrace of global capitalism during the late 20th century.

It’s also one of several works demonstrating Wang’s obsession with corporate logos. When China’s economy began to open up, the artist recalls being captivated by the foreign products that flowed into the country.

“When I drank cola for the first time, I thought it tasted like urine, and it made me uncomfortable,” he says. “But when I got used to it, I found it’s f***ing good.”

For Wang, modern brands have an almost mystical quality, and he views them as a cipher for the “Western cultural spirit” that’s seeped into China.

In a recent work, he asked his audience to interrogate their loyalty to brands in the most direct way possible: He spent four months painting hundreds of logos onto a wall, then added a huge question mark in the middle.

The process of creating the mural — which he titled “Question a Brick Wall” — was so painstaking, it exacerbated his farsightedness and forced him to buy new spectacles.

The 54-year-old’s cynicism toward big business is partly a result of his background. Born in Daqing, an oil town in China’s freezing Northeast, Wang grew up among rig workers. His father died when he was still a teenager, and so Wang joined a drilling team straight out of high school to support his family.

It wasn’t until seven years later that Wang was finally able to pursue his artistic passion, gaining a place at the Sichuan Fine Arts Institute. After finishing his program in 1993, he joined the army of beipiao — or “Beijing drifters” — trying to scrape a living in the capital.

His experience living in one of Beijing’s many slum-like neighborhoods led to one of his well-known early works, 2005’s “Dream of Migrants.” For this piece, Wang hired dozens of actors to play a variety of roles, from street vendors and migrant workers, to naked couples having affairs.

The photograph highlights the tragic condition of Beijing’s migrants at the time, their poor living quarters contrasting with their aspirations for a better life. Wang says he felt their pain keenly, as he used to be one of them. “I’m empathetic to this migrant population,” he says.

Over recent years, however, the artist has found himself increasingly removed from his working-class roots. His work has achieved extravagant commercial success, with “Follow Me” selling for 433,000 pounds (then $860,000) at a London auction in 2008. He still holds the title of China’s most expensive photographer.

Today, Wang tries to distance himself from his “price tag” and insists that “art is a kind of labor.” These efforts might also explain his unique hairstyle, which has been a trademark of his for over a decade.

At first glance, the artist looks bald. On closer inspection, however, there are fine gray hairs springing up from all over his scalp that hang around his head like a fine mist. According to Wang, he asked his barber to cut off all his black hairs, but leave the silver ones — a job that took three hours to complete.During a recent exhibition, the artist even appeared to satirize his own fame — and the world’s growing love for authority figures — by hanging a giant portrait of himself in the gallery and inviting visitors to paint him.

After a period of grief mourning the deaths of his mother and brother, Wang says he feels a renewed sense of urgency toward his work. In 2017, he got a tattoo of a fast-forward button on his left wrist, to remind him not to slack off.

“After my mother passed away, I reduced the saturation level in all my works by 30%,” he says. “I see (the tattoo) as a totem … Maybe I can have an Indian summer.”

After over a decade documenting Chinese society, Wang has created just around 100 of his giant photographs. He continues to add two or three each year. Once he’s finished, he hopes they’ll remain as a monument to his life.

“It’s like a painter — they paint their whole lives, and really what they’ve done is paint a self-portrait of themselves,” says Wang. “Us photographers are the same.”

Additional reporting: Shi Yangkun; editor: Dominic Morgan.

(Header image: “Follow Me,” 2003. Courtesy of Wang Qingsong)