Dumplings and Dialogue: A Former Student Remembers Ezra Vogel

News of the passing of Harvard professor Ezra F. Vogel has been met with shock and sadness in China. Media outlets and academics alike have posted memorials and retrospectives praising his wisdom and thanking him for helping the outside world better understand their country.

But Vogel was more than just the former director of Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, the author of masterworks like “Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China,” or a torchbearer for Sino-U.S. studies. To me, and other students like me, he was “Grandpa Fu,” that much-loved professor who, every month, invited students and researchers from China to his home to eat dumplings and chat.

From 2011 to 2012, I was a visiting fellow at the Harvard-Yenching Institute. The winter nights in Cambridge are always cold, but once a month, no matter how freezing it was, I would rush out the door and head to the professors’ residential area. Sometimes I'd get a little lost in front of so many similar-looking buildings, but never for long. That’s because the door to one was always open; its warm porch light and the smell of food being cooked within called to me, as if to say: “This is the place!”

“This” was the home of Professor Vogel, whose dinner and study group on China studies, organized with Professor Martin Whyte, was a long-standing tradition at Harvard. I can’t even begin to imagine how many Chinese students or visiting scholars to the university spent time in that small building over the years.

Professor Vogel’s concern and care for young scholars was widely known throughout the academic world. We showed up to his door brimming with dreams and ambition — and no idea if we were supposed to take our shoes off before entering his home. Yet we were always warmly ushered in by him and his wife (our shoes still firmly on our feet). We’d carefully place our bags on the floor of his bedroom, and then we’d join the line for a sumptuous buffet.

Over dinner, Professor Vogel became Grandpa Fu — a play on his Chinese surname. Back then, his magisterial “Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China” had just been published, and he had a copy displayed prominently on the bookshelf in his living room. He explained to a rapt audience how he had toiled for a decade to write the book, how he’d gotten those who knew Deng best to open up, and the difficulties he’d faced during its translation and publication processes. We laughed often while we ate, then crammed into the kitchen and clumsily helped load the dishwasher.

I still remember how, at the first dinner after the 2011 Christmas vacation, I had the chance to talk about a paper I’d written: “Labor Enthusiasm and Deception.” As an assignment for one of Professor Whyte’s courses, I’d explored how people’s enthusiasm for production in the early days of the People's Republic of China devolved into deception, abuse of power for personal gain, and discontent during the Great Leap Forward of 1958 to 1962.

Some of those attending the dinner didn’t know much about that period in Chinese history and frequently cut in with questions. For example, when I mentioned that the southern Guangdong province had “launched a satellite” during its steel production campaign, someone interrupted me to ask: “What do you mean ‘launched a satellite?’ How could factories have satellites?” Quick as a flash, Professor Vogel explained that “to launch a satellite” means “to boast or exaggerate.” Although the country’s factories could not produce large amounts of steel, managers declared higher outputs anyway in order to pander to their superiors. In this way, production gains suddenly appeared stratospheric — just like a satellite being launched into space.

The discussion over dinner that evening was lively and lasted late into the night. I can still remember Professor Vogel smiling amiably, while Professor Whyte furrowed his brow, as was his habit. The advice they gave me was consistent and to the point, and my article was published later that year in the 10th edition of the Chinese journal Open Times.

It’s been eight years since I left Cambridge. Originally, I had meant to return this year. I’d organized a panel session for the 2020 conference of the Association for Asian Studies, which was to be held in Boston in March, and had applied to return to the Harvard-Yenching Institute as a visiting professor. I’d already made up my mind that I simply had to see Grandpa Fu again and attend another of his dinners.

Then the coronavirus came and put an end to all my plans. Now, during yet another cold winter, comes the devastating news of Professor Vogel’s sudden passing.

Sometimes I look back at my year in Cambridge, and how, whether we realized it or not, we were witnessing the end of an era. President Donald Trump’s administration has lowered the curtain on decades of globalization, and friction over trade and technological competition between China and the U.S. has only intensified. We seem set to return to the political lines and ideological confrontation of the Cold War era.

China and the United States face many of the same challenges: the myopia of financial capitalism, the hollow prosperity generated by abstract economic development, environmental collapse spurred on by global warming, unstable jobs for the many and the concentration of wealth for the few, and the crisis of an aging society. Given these risks, it’s only natural for people to see everything as a competition and look for ways to protect themselves, even at the expense of others. However, competition and self-preservation will not solve these problems, only exacerbate them further and lead us all into disaster.

Professor Vogel argued that, although the U.S. was a leading party to the Cold War, American China-watchers were never among the country’s Cold Warriors. Whether during the McCarthyism of the 1950s or the frequent frictions of the past four years, Professor Vogel’s actions consistently promoted dialogue between the two nations. The dinner parties he organized at his home are a testament to this.

Now he’s gone, but the light in front of his house will always shine on in our hearts. I only hope we can live up to his example of in-depth and sincere academic exchange, dialogue, and discussion, and together create a new era he would be proud of.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell; portrait artist: Wang Zhenhao.

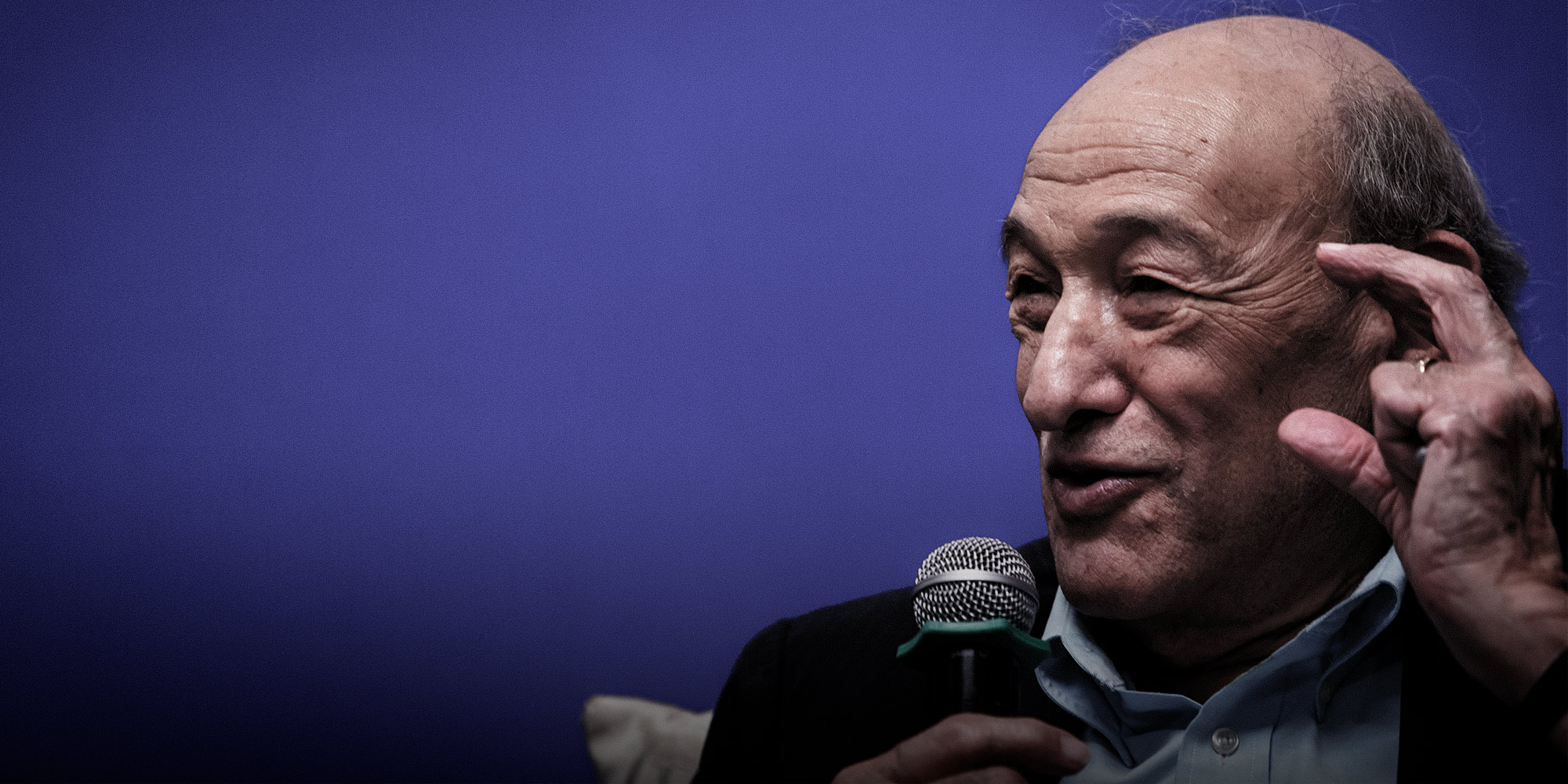

(Header image: Ezra Vogel during a forum in Beijing, 2013. Zhan Min/People Visual)