State Prosecutions Aren’t the Only Answer to China’s Libel Problem

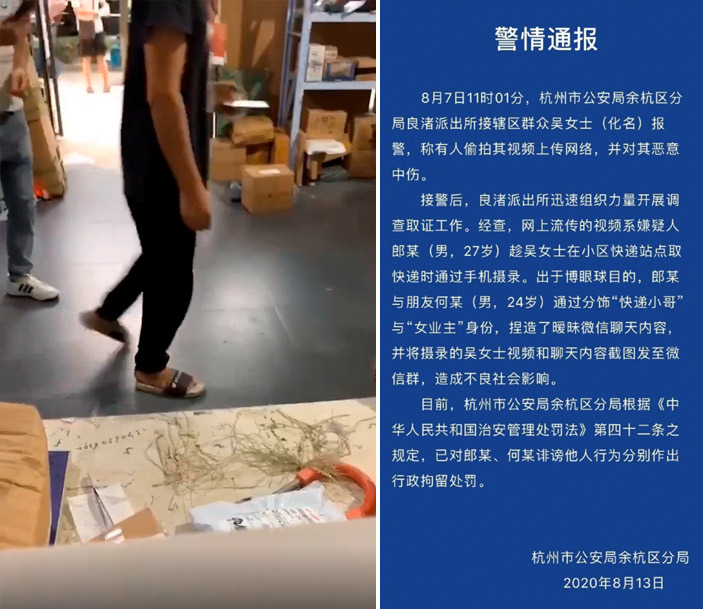

Last July, a woman, surnamed Gu, went to collect a package at the gate of her residential community in the eastern city of Hangzhou. Little did she know, her entire life was about to be upended. While she exchanged a few polite words with the courier, the owner of the convenience store next door, identified in court documents by his surname, Lang, recorded the conversation between the two on his phone. Then, with the aid of his friend, surnamed He, he falsified screenshots of a chat log between the courier and a “lonely young woman,” which they shared in a chat group.

According to Lang, they were just having a bit of fun with the chat group’s members, but things soon got out of hand. The messages and photos went viral on Chinese social media, with salacious headlines like “Rich Lady Cheats on Husband with Young Courier.” As the messages made their way across the internet, Gu fell victim to an online hate campaign. Although the police later identified Lang and He as the culprits, in the weeks after the incident Gu — referred to in earlier media reports by a pseudonym, Wu — says she was admonished by her neighbors and pushed out of her job, even experiencing bouts of depression.

Eventually, Gu decided to hire a lawyer and file a private criminal complaint with a court in Hangzhou, requesting Lang and He be held criminally liable for defamation. The court accepted her case on Dec. 14. However, not long after, the public prosecutor’s office announced that “Lang and He’s actions have not only harmed the victim's personality rights, but also ... created a sense of insecurity among the general public as well as severely endangering social order.” Therefore, based on the second paragraph of Article 246 of China’s criminal law, the office decided to intervene in the case and initiate a public prosecution.

Social media users eager for justice have applauded the decision, but the response among legal scholars has been mixed. In effect, it means that a public prosecutor, and not the victim, will take over the prosecution of this case, and some experts worry it might be an example of overreach into what should be a private criminal matter.

People who do not understand the nature of defamation suits or the Chinese judicial system might wonder what the big deal is: After all, isn’t the ultimate result still a trial?

But in reality, the conviction rates of cases differ tremendously depending on whether they’re heard through private or public prosecutions. Having researched 151 verdicts in China from 2014 to 2018, the academic Zheng Haiping found the proportion of defendants found guilty and sentenced in public prosecution hearings was 100% in cases wherein the victim was an ordinary citizen, compared with 35% in private prosecution hearings. Similarly drastic disparities were also present in other types of cases. The public prosecutor’s office has broad latitude in carrying out investigations, which, when coupled with the traditionally close ties between the police, prosecutors, and courts in the Chinese justice system, often gives them a leg up in securing convictions and sentences. By comparison, complainants in private prosecution cases often struggle to compel defendants to comply with their requests, making it difficult for them to acquire key evidence.

Thus, from a practical standpoint, the public prosecution of defamation cases increases the odds of a successful suit. In cases like Gu’s, where real harm was caused to a non-public figure, this can seem a welcome intervention. But securing a conviction shouldn’t be the sole criterion of criminal proceedings. Procedure matters.

Under China’s criminal law, defamation belongs to the category of crimes to be “heard only upon complaint.” In other words, unless an instance of defamation “seriously endangers social order and national interests,” the onus is on the complainant, in this case, Gu, rather than a public prosecutor, to bring their own case before the court. This procedural provision is not unique to China. For example, the German Code of Criminal Procedure also provides for the private prosecution of relatively minor offences such as insults and commercial bribery, and it leaves room for the parties involved to settle the matter out of court.

If the line between private and public prosecution lies in whether the crime endangers the interests of an individual or the public, debate among Chinese criminal law scholars has focused on how exactly to make that determination in defamation cases. Some scholars are of the opinion that, because the suspect in the Hangzhou case defamed a random individual, the damage was not limited to just Gu and her reputation: Lang and He had created a general sense of insecurity in society at large. Therefore, they believe that public prosecutors should assume responsibility for this case and others like it to prevent such behavior from becoming commonplace in the future.

Other scholars argue the criminal justice system should not become overly entangled in the private sphere and worry that carelessly elevating the social impact of acts such as defamation to the level of “disturbing public order” may suppress freedom of expression. Previous judicial interpretations — de facto laws in China — issued by the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate have generally sided with this second group, at least on the issue of public order, setting strict standards for just what kind of defamatory behavior is entitled to public prosecution.

Ultimately, given the high conviction rate of public prosecution cases, encouraging public prosecutors to intervene indiscriminately in defamation cases under the pretext of “maintaining public order” may, on the surface, seem like a good way to deter people from engaging in defamatory behaviors in the future. Yet in the long run, cultivating this impulse could have unintended side effects, such as turning defamation into a “pocket crime,” a term for vaguely defined offenses that can be used to prosecute people on almost any pretext.

Advocating for a more prudent approach to public prosecutions and making private prosecution the main means of combating defamation does not absolve the state of responsibility. If the main challenge for successful private prosecutions is obtaining evidence, China’s existing laws already offer at least one solution: If a complainant explains to the court that a defendant has withheld relevant information, the court may then request a public security organ to launch an investigation and hand over any evidence to the complainant and their lawyers. Indeed, this is exactly what happened in Hangzhou, even before the prosecutor’s office stepped in.

The law could also help victims by appropriately reducing standards of proof. Under current law, the determination of defamation often depends on the defendant’s confession and whether or not it shows “subjective criminal intent.” This makes successfully prosecuting defamatory behavior exceedingly difficult. If China were to draw inspiration from certain parts of the United States — where, in defamation cases involving non-public figures, one only needs to prove negligence, rather than malicious intent — then it would be much simpler to deal with cases like the one in Hangzhou. All a victim like Gu would need to do to bring her slanderer to justice is prove that the cheating scandal was a fabrication, and that the spread of false information was such that it harmed her reputation or mental health.

In this era of “social death,” where fast-spreading fake news and online mob justice can ruin a victim’s life in an instant, there’s no denying the importance of holding people responsible for their speech. But this does not mean that state organs have to assume total control over every aspect of legal proceedings. Continuing to rely on private prosecution as the default channel for seeking justice in defamation cases, lowering the standard of proof for victims of defamation, and, if necessary, enlisting state organs to help them obtain evidence is a far more balanced and appropriate way to ensure the fairness of the judicial process and protect victims’ rights.

Translator: Lewis Wright; editors: Cai Yineng and Kilian O’Donnell.

(Header image: Alice Mollon/Ikon Images/People Visual)