It’s the Year of the Ox, So Where’s the Beef?

It’s once again time to celebrate Lunar New Year, and there’s reason for optimism as families across China turn the page on the turbulent Year of the Rat and prepare to welcome the Year of the Ox. The ox has long been an auspicious symbol in Chinese culture as one of the “six domestic animals,” alongside horses, sheep, pigs, dogs, and chickens, and the Chinese idiom “the six domestic animals are thriving” is another way of saying the nation is prospering.

As foodstuff, however, beef has a more complicated history. The more than 2,000-year-old compendium the “Book of Rites” refers to the sacrifice of a cow, sheep, and pig as the greatest level of offering, with cows enjoying the highest status of the three. And outside of their use in rituals, meals of beef and mutton were enjoyed by the nobility of the time.

Yet by the late Spring and Autumn period (771-476 B.C.), the growing use of iron plows pulled by oxen reenforced the animal’s importance to agricultural productivity. Over the ensuing millennium, the rulers of successive Chinese dynasties issued decrees forbidding the slaughter of cattle. In particular, the imperial court of the Tang dynasty (A.D. 618-907) and its successor states introduced strict protections for oxen used in plowing, making their killing a serious criminal offense on par with counterfeiting or homicide.

Among ordinary people, especially in the Chinese agricultural heartland south of the Yangtze River, the taboo on slaughtering oxen or buffalo was so strong it was frequently included in clans’ ancestral rules. Various works of art also encouraged the idea of not eating beef: Poems and stories tell of people dying from uncontrollable itching brought on by beef consumption, and, conversely, of people being spared by malevolent spirits because they avoided eating the meat throughout their lives. Some texts went so far as to place “not eating beef” on the same level as “accumulating family merit for three generations” when it came to safeguards against plague-spreading evil spirits.

Of course, for every rule, there are those willing to break it. For example, the renegade heroes of the classic novel “Outlaws of the Marsh” are always asking tavern keepers for “5 jin (2.5 kilograms) of your finest beef.” As a plot detail, it’s a way of signaling not just that the protagonists have a hearty appetite and are in good health, but also that they’re willing to challenge the laws of the land and local taboos. Chinese Muslims, too, were allowed by the government to slaughter cows and sell beef.

Ultimately, though, cattle were not thought of primarily as a source of meat in China until very recently, after the opening of the country to Western ships and, more importantly, Western missionaries.

After being forcibly opened to international trade in 1843, Shanghai quickly replaced the southern city of Guangzhou as the country’s hub for Chinese-Western commerce. It also became a center for “Western” culinary culture China. In Shanghai’s concession areas, the influx of foreigners led to a boom in demand for beef, milk, cheese, and other foods not traditionally consumed in the region. At the time, there were no farmers in or around Shanghai raising cows specifically for food, only water buffalo for farming. While these animals might be killed when they got too old or sick to work, the resulting beef was deemed inadequate in both quantity and quality by the city’s growing foreign population.

As such, the foreign-controlled Shanghai Municipal Council tried to coordinate with the local authorities to encourage farmers in the agricultural hinterlands now known as Pudong to raise and trade cattle, but their entreaties were repeatedly rejected. Instead, traders began bringing cattle to Shanghai from the neighboring Jiangsu province and selling them to foreign butchers.

Having solved the immediate issue of procuring their daily bread and beef, the city’s foreign residents set about doing what they did best: evangelizing, not just for Christianity, but for Western culture writ large, including Western cuisine. Missionaries and evangelists such as John Dudgeon, Henry W. Porter, and Mary Stone published articles on the benefits of Western food in church magazines like Child’s Paper, The Globe Magazine, and Woman’s Messenger.

These articles were intended to popularize concepts like nutrition, diet, and food science to Chinese readers, and beef was a particular focus. For example, the 19th century English Anglican missionary John Fryer ran a serialized translation of the early health and nutrition manual “The Chemistry of Common Life” in his Chinese-language Scientific and Industrial Magazine, informing readers that “beef and bread are the staples of English life.” In 1889, the American Presbyterian Mission Press translated and published “The Oriental Cook Book,” which became one of the most important Western recipe books in China during the late Qing dynasty (1644-1912). Near the beginning, it says: “Beef is … one of the most nutritious kinds of meat.” It then goes into detail about how to choose good beef, as well as the best cooking methods for different cuts including veal, ox tongue, and ox heart.

Soon enough, the idea that beef was a nutritious and healthy choice began taking hold among Chinese. Just as important, it became fashionable: As more and more Western restaurants began opening up in Shanghai’s concession areas and across China, going out for walks and eating large, beefy meals gradually became symbols of a modern lifestyle — and the focus of regular attention in the pages of popular publications such as “Dianshizhai Pictorial,” “Feiyingge Pictorial,” and “The Pictorial Weekly of the Eastern Times.”

It wasn’t long before this trend started to spread outside of Shanghai and across China, though initially it remained confined to elites. Foods popular in the West, such as milk, cheese, beef, and beef extract, gradually became important staples among China’s upper class of scholar-officials, who prized them for their supposed nutritional value. Letters sent by prominent late-Qing dynasty court ministers like Weng Tonghe, Chen Baozhen, Zhang Yinheng, and Li Hongzhang reveal that beef extract had become something of a hard currency among officials during the late Qing.

Eventually, non-elites started to follow their example, and by the early 20th century Chinese of all social classes were extolling the nutritional effects of beef tea and tonics. For the first time, beef was something ordinary people could — and would — aspire to consume.

Translator: David Ball; editors: Wu Haiyun and Kilian O’Donnell.

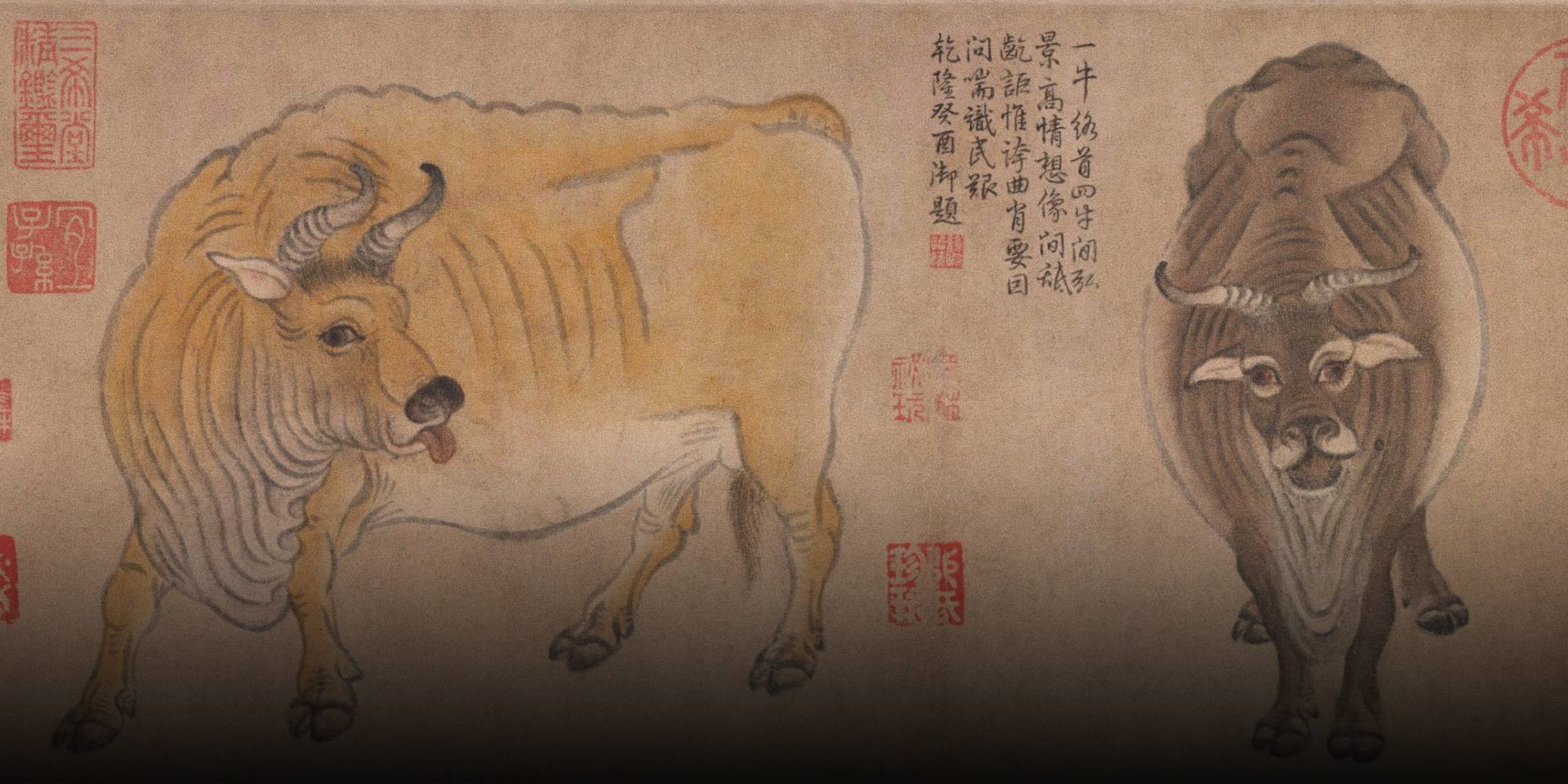

(Header image: Detail of “Five Oxen,” by Tang Dynasty official Han Huang (723 –787), from the collection of the Palace Museum. From Wikipedia)