China’s Primary School Parents Anxious Over No-Homework Rule

To ease the burden on overwhelmed schoolchildren, China’s Ministry of Education has announced that primary schools should no longer assign homework. But far from the desired outcome of relieving stress across the board, the new policy has parents and teachers worried.

“Exercises should be finished before students leave campus,” Chen Baosheng, the country’s education minister, said Thursday. “The responsibility to teach should return to the school, as families have other responsibilities,” Chen said, referring to the current status quo, under which Chinese parents shoulder much of the responsibility for providing their children with a comprehensive education. The minister added that parents should “guide students to independently manage their studies.”

The ministry also said middle schools should not assign children homework that’s beyond the scope of the material in their textbooks. It did not explicitly say how the new rules would be enforced, or whether schools would be punished for failing to comply.

“The intention and purpose of this guidance are good and clear,” Cui Yunhuo, dean of the Institute of Curriculum and Instruction at East China Normal University, told Sixth Tone. “What’s important to note at the implementation level is that this guideline is aimed at banning repetitive written assignments, not practical assignments.” Despite Cui’s interpretation, it is unclear whether the guideline will apply to all homework or only written homework.

The professor added that the ultimate goal is to “improve the quality of assignments and early education,” referring to a need for more hands-on homework, as well as tasks that emulate real-life scenarios.

According to Cui, the problem of excessive homework during China’s compulsory education period — primary through middle school — has no one root cause. To improve the quality of education, social institutions should be more engaged in researching higher-quality assignments, rather than continuing to rely on rudimentary assignments that are time-consuming but meaningless.

Just days before, the ministry had announced a nationwide prohibition on primary and middle school students bringing cellphones to campus. But it’s the latest decree that has generated more buzz.

“This rule is impossible to enforce,” a fourth grade teacher in Shanghai’s Huangpu District, surnamed Shen, told Sixth Tone. “I don’t believe any school will strictly abide by it. Who will be supervising them, anyway?”

According to Shen, who only agreed to give her surname due to the sensitivity of the matter, primary schools were already encouraged not to assign homework to first and second graders. “But only a few schools in Shanghai, including those in Huangpu, have been following the rule,” she said. “And what has been the consequence? Our students’ academic performance is among the worst of any district in the city.”

In August 2018, the Ministry of Education said first and second graders should not be assigned written homework. The motivation at the time was to prevent children from developing eyesight problems. By 2018, 36% of all primary schoolers in China were nearsighted, while the proportion grew to 71.6% and 81%, respectively, for middle and high schoolers.

Now, some parents who once complained about having to help their kids complete their homework assignments are feeling anxious.

“If the school doesn’t assign my child homework, that means I’ll need to find the right exercises for him to do myself,” Xu Qing, the mother of a first-grader in Shanghai’s Pudong New Area, told Sixth Tone.

Xu did not academically prepare her son for primary school — he was just a young child, after all — so the homework his Chinese and math teachers assigned from the first semester became a big headache for her. Xu said she would spend up to three hours each evening helping her son on his homework.

The education ministry’s new policy says primary schoolers should finish their work before leaving campus, but Xu isn’t confident her son will be able to manage this. “He’s slow to finish those assignments, and I worry this will be too much pressure for him,” she said.

However, other parents have reacted to the new announcement with more equanimity.

“When it comes to my son’s education, I’ve never relied on his school,” Cheng Lina, the mother of a first-grader in Shanghai’s Xuhui District, told Sixth Tone. “With public primary schools at least, the material they teach is too simplistic.”

Instead, Cheng sends her child to local cram schools, and together with her husband provides extra instruction in Chinese, math, and English. “That’s why I don’t really mind,” she explained. “But honestly, given this new policy, the achievement gap between kids could become more apparent — if the parents are good teachers themselves, or if they’re financially well-off, their kids will have a better chance of standing out among their peers.”

A math teacher from the same district expressed similar concerns. “The new rule will make the extracurricular training market even crazier,” she told Sixth Tone on condition of anonymity. “If the new rule is strictly implemented, teachers are going to face more pressure and have to stay longer with students on campus to ensure that they all finish their work. It will mean extra hours for us.”

For Shanghai’s primary schools, the day typically ends at 3 p.m., and even earlier on Fridays. But in Beijing, where schools finish at around 5 p.m., parents have been more receptive to the new policy. “This means schools will improve their efficiency,” one mother of a fourth-grader in the capital told Sixth Tone.

Education writer Amber Jiang also said that, based on her impressions, parents in Beijing seem mostly satisfied with the new rule. “This will mean that more off-campus time can be reserved for extracurricular exercises,” she told Sixth Tone. “Above all, the material taught by public schools is too basic: Children need supplementary learning.”

Additional reporting: Zhang Shiyu; editor: David Paulk.

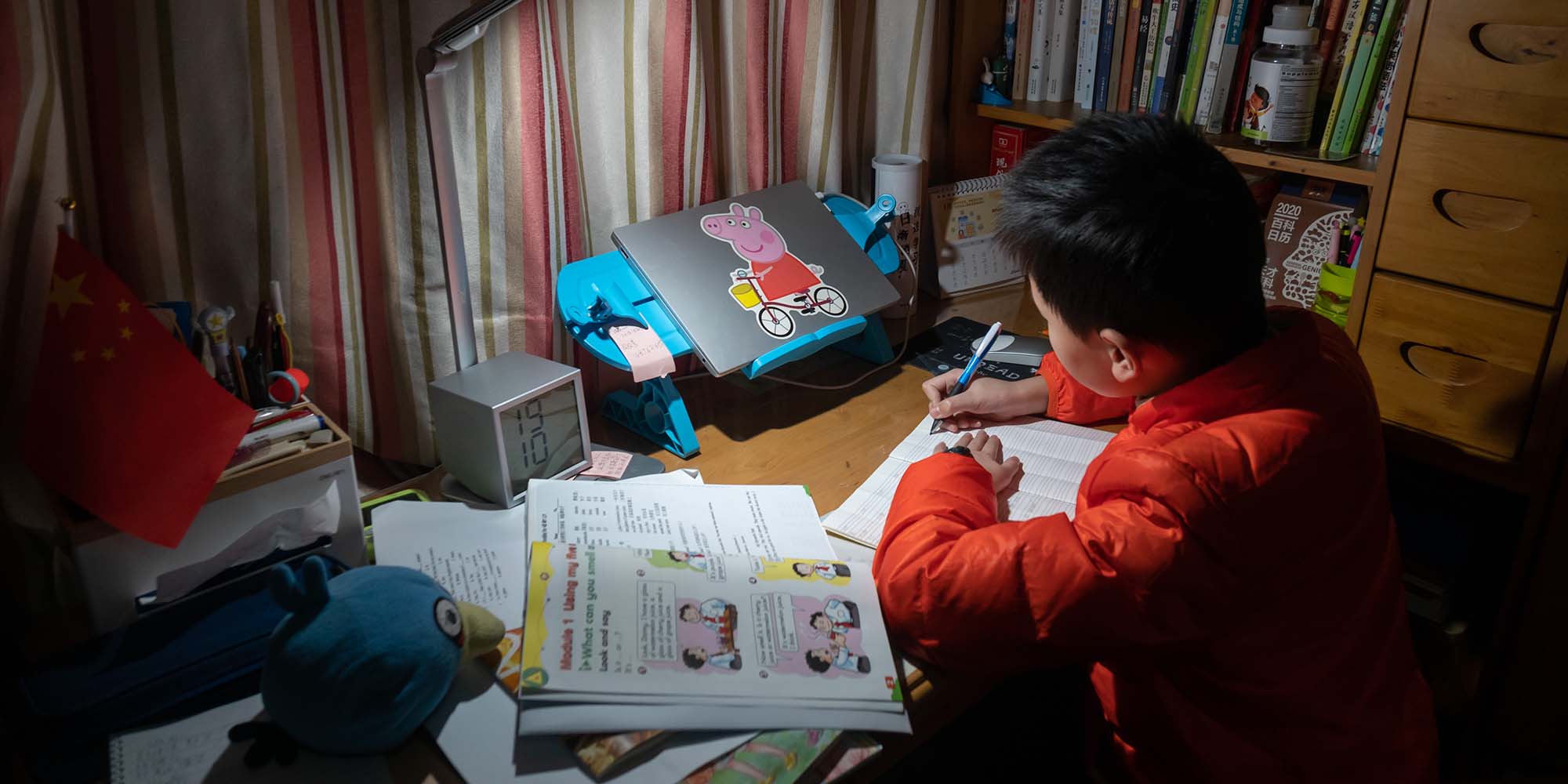

(Header image: A boy does homework at his home in Shanghai, March 3, 2020. People Visual)